It is a small but powerful image. This power is based on its pictorial conciseness, its artistic quality. My reflection on the woodcut is based on a suspicion. Obviously, its message is problematic. At the beginning of the modern era in Europe, it formulates a worldview that has had great influence and fatal consequences to this day: the destruction of diverse nature and culture in the course of the anthropocene and colonialism.

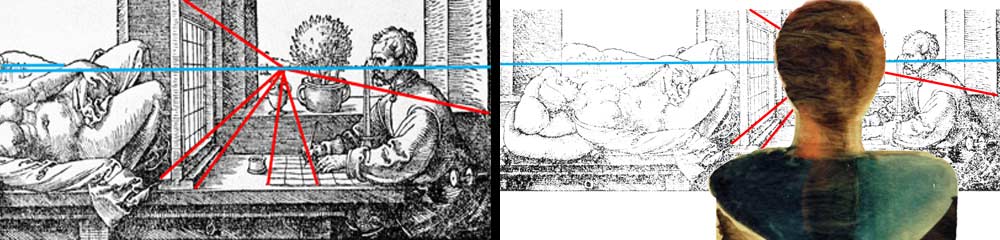

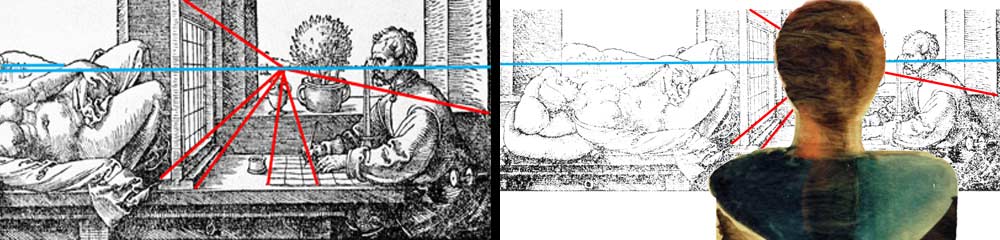

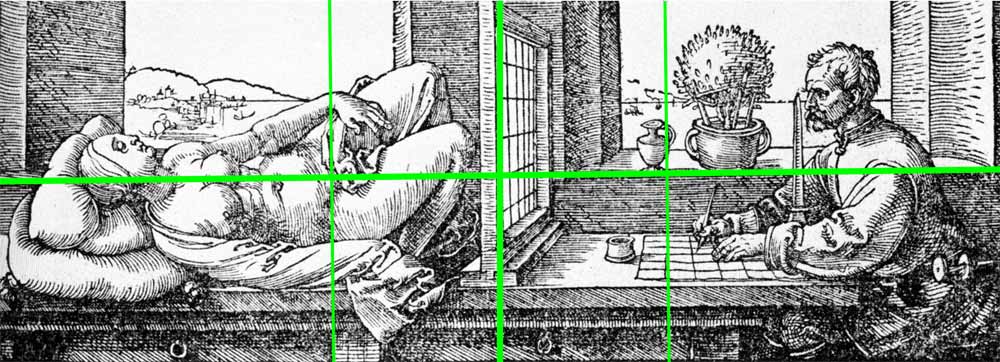

On the left construction of the horizon and vanishing point, on the right with the viewer inserted (visualisations by the author)

With the help of this grid, he succeeds in creating a way of convincing representation, an interpretation that photography (invented almost 400 years later) would also deliver. I.e. a representation that is ‘correct’ in terms of perspective.

The woodcut itself also follows this principle of ‘correct’ linear perspective. The horizon is marked as the sea horizon in the right-hand window; the vanishing point of the grid lying on this horizon. This vanishing point also assigns a specific, clearly determined space to the viewer's eye. It is at the same height as the depicted artist, and on the right, the ‘male side’ of the image. In this way, the viewer is not only a witness to the event, but also a confidant and accomplice of the drawer / the artist.

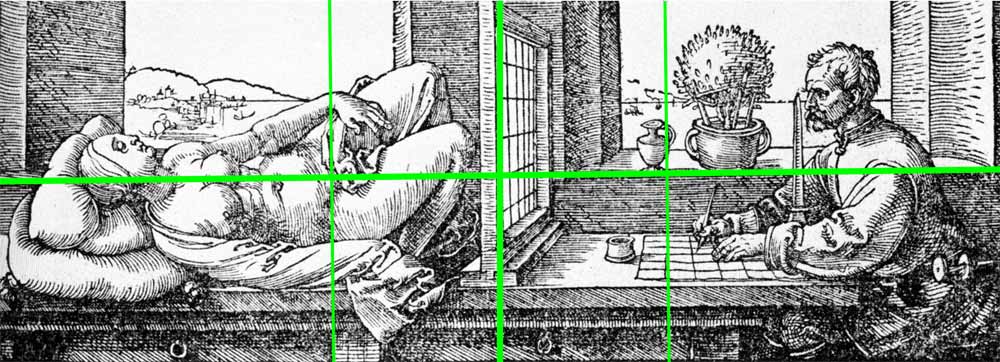

In terms of composition, the symmetrical layout is particularly striking. As in a coat of arms, we see two equal-sized fields on the left and right, divided by the grid frame. In both parts, two windows, also of the same size - each with a view to the outside.

Subdivision according to centre lines, additionally thirds. The vanishing point is on the right perpendicular.

In the left part of this emblematic image, the woman. The flowing cloth emphasises her nakedness rather than covering it. She is bedded on soft cushions, 'lying according to the artist's will' (to speak with Dürer in his accompanying text). Her raised lap turned towards the man, her eyes look closed, her left hand rests on her thigh. The table on which she lies works as a presentation plate.

Dichotomies

With this composition, the image formulates an almost striking dichotomy. To name just a few aspects that are particularly significant in our context:

|

|

|

|

- Woman: naked and thus ahistoric, i.e. "timeless", with closed eyes and diffuse spatial orientation.

|

- Man: clothed and armed, watching closely, focused on the woman in front of him.

|

- Woman: In her passivity she has a powerful presence in the picture; she is - lying - the theme (the

object) of the emerging drawing. |

- Man: He is actively engaged, sitting, taking action. He is an individual

subject, drawing the ‘object’ on paper. |

- In the window: 'free', lively nature.

|

- In the window: reduced nature, mostly just the horizon line.

|

- Tall, naturally growing trees outside in the open air.

|

- One small, domesticated and cultivated 'tree' in a pot, indoor.

|

This dichotomy is not only emphasised by the narrow format and the symmetrical layout, but above all by the clear separation of the two ‘worlds’, which is achieved by means of the grid frame, i.e. an important tool in (Dürer’s) art. This again cements the structure of distance established by the artist: On the right, the male attention to the woman is conceived as (and through this reduced to) distanced looking and the spellbinding drawing of what he sees. The woman, on the other hand, presents herself - against a lively backdrop - as the ‘target object’ behind the frame. In this way, however, it is not only the clichéd gender roles being fixed, gender roles as they will be significant throughout the next centuries. But there is more at stake.

Panofsky had characterised this kind of linear perspective "as a symbol of a beginning, when modern anthropocracy was setting itself up" (1980: 126). That perspective initially puts the world at a distance. Above all, it opposes ‘subject’ and ‘object’ to each other in a clearly separated way. The aim of this procedure and the underlying model of thinking is to make the world 'calculable' in a 'modern' way: At last, even in a picture, one can say whether a line, a shape is right or wrong. The world is thus degraded to a supplier of 'appearance data' (Rebel 1996: 198). The data selected are now recorded - through a technical procedure - by the isolated and disembodied eye. In this process, the eye is the representative of a specific 'pictorial intellectuality'. Dürer emphasises: "the eye is the noblest sense of all" (Rebel 1996: 200). This gives the rational mind the decisive role, which becomes the ‘signature’ of the Renaissance. And, perspective is its symbolic form, its paradigm. Linear perspective represents "the world as it can be in the idea alone. It constructs the world" (Belting 2008: 27) according to cognitive principles.

In the woodcut, this rational, intellectual way of seeing belongs to the man. The woman, on the other hand, has her eyes closed, she does not look. (She is looked at.) With regard to the anthropocratic claim of the (male) rational mind, woman (as a sensually tangible allegory) thus becomes the indeterminate, unmarked “Other” (Latour 2017: 38). Ultimately she becomes the representative of the natural: she is naked, ‘as nature created her’ and thus timeless, i.e. untouched by a specific contemporaneity. She must - in order to become visible - be 'captured' by the man on the right, who has an individual face and is dressed in a contemporary manner.

Above all, the specific form of relationship of the two sides to each other are decisive for our question. As already shown, we find here a clear subject-object relation. The man (who represents civilisation, culture, the domestication of nature) is the active, acting, looking, mentally grasping subject who now ‘subjects’ the woman as a passive object to his artistic appropriation (and through this the 'naked', non-civilised nature that is embodied by her).

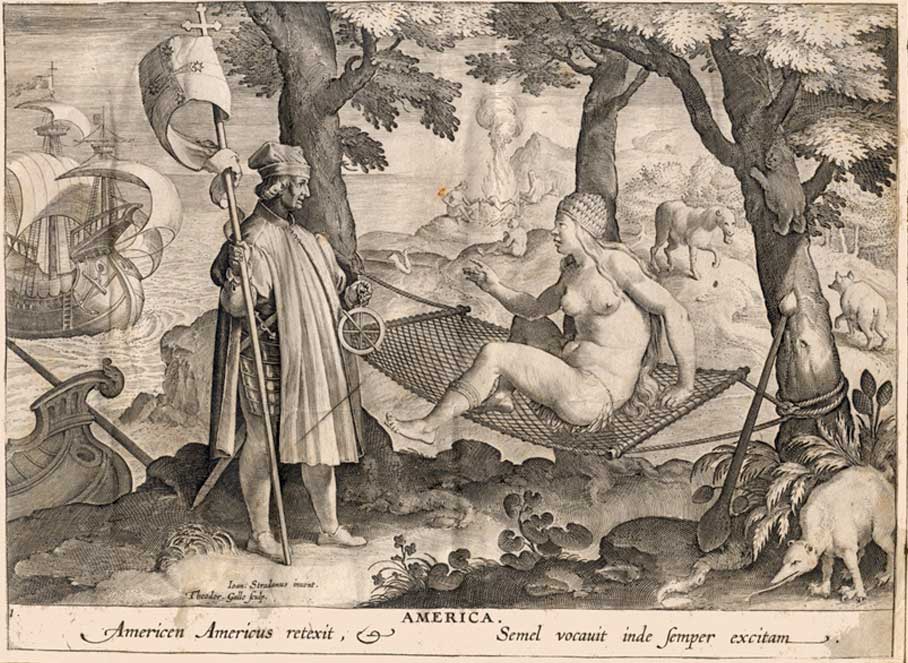

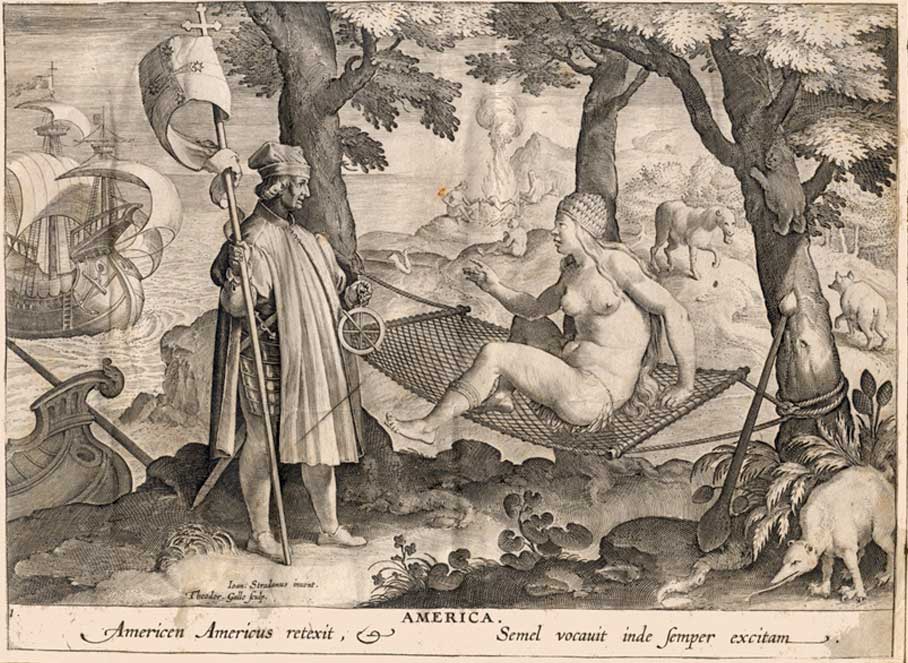

Latour points out that this conception is specifically European: "What occidental painting invented [...] and of which no trace can be found in any other civilisation" (Latour 2017: 38). From there, there is an striking parallel to the conquest of the "New World" by European powers in colonialism, as the image below shows.

References

- Belting 2008: Hans Belting. Florenz und Bagdad – Eine westöstliche Geschichte des Blicks. München (Beck)

- Latour 2017: Bruno Latour. Kampf um Gaia. Berlin (Suhrkamp)

- Panofsky 1980: Erwin Panofsky. Die Perspektive als „symbolische“ Form. In: Erwin Panofsky. Aufsätze zu Grundfragen der Kunstwissenschaft. Berlin (Volker Spiess)

- Rebel 1996: Ernst Rebel. Albrecht Dürer, Maler und Humanist. München (Bertelsmann)

- Zur Lippe 1981: Rudolf zur Lippe. Naturbeherrschung am Menschen. Bd. 1. Frankfurt (Syndikat)