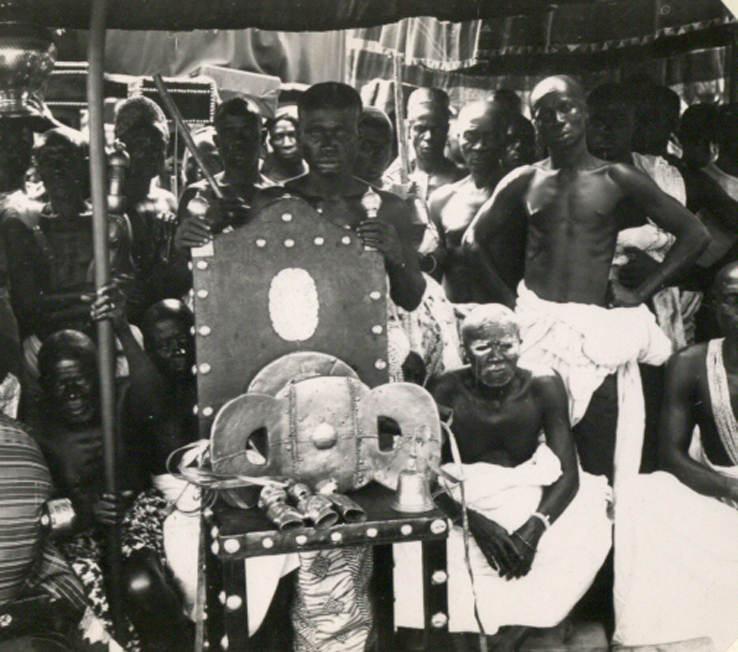

The Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu stool is a carved traditional wooden stool designed with an Akan symbol known as Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu (pronounced ‘fuun-tum-fu-ne-fu den-cheem-fu-ne-fu). This type of stool called asԑsԑgua in Fante (a dialect of Akan people from Ghana) is an art-cum-utilitarian object. It is basically composed of three main parts namely the animu (top) which is the seat; the mfinfinin (middle) which bears the design that gives identity to the stool; and the wiabour (base) which is the part that touches the ground and gives stability to the stool (Antubam, 1963; Amenuke, Dogbe, Asare & Ayiku, 1991). In this particular image, the middle portion, which is the focal consideration for this presentation, is created with the Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol. The size of the stool is composed of a base that measures 53cm x 28cm, the top arc-shaped seat that gives the stool a length of 55cm and an overall height of 42.5cm.

The stool was presented as a special gift to the Chairman of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), who doubled as the then Head of State, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings by the Chiefs and people of Dormaa in the Bono Region of Ghana. It was brought to the Ghana National Museum through the State protocol in 1992. Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings led Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (A.F.R.C) to power through coup d’état on June 4, 1979 and prepared the grounds for the coming of the third republican constitution. In the same year, Dr. Hilla Limann was inaugurated as the president of the third republic after winning the election. Rawlings returned to power on December 31, 1981 through another military takeover with his Provisional National Defence Council (P.N. D.C) of which he was the chair. Rawlings’ PNDC party stayed in power for almost eleven years before working out for the adoption of the Fourth Republican constitution through a referendum on April 28, 1992 (Essel, 2019). Subsequently, presidential election was held, which he led the National Democratic Congress (NDC) to win. Though the exact date he received the stool as a gift is unknown, it might have been received within 1981 to 1992, judging from the period of his military regimes and constitutional terms of office before the Ghana National Museum received the stool as part of its collections.

The artist who carved this stool is anonymous. Within the context of the Ghanaian traditional creative work productions, this is not strange, since artworks produced in precolonial and traditional Ghanaian societies were hardly signed by the artists who produced them. This was because the artworks were communal, that is, they were produced for use by the community. The chiefs and kings had varied proficient artists in their courts or communities who produced artworks for the community. With the Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu stool being a special gift to the then president of the state, it might have been created by a revered and creative carving-artist in the Dormaa community.

The Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol falls within tangible artistic creations which takes its name from the Akan expression for Siamese crocodile. Akan is a major Ghanaian language, which is spoken by about 48 percent of Ghana’s total population as first language, and by an additional 35 percent as additional first language or second language (2010 Population and Housing Census). The symbol derives its name from an Akan proverb which suggests that the Siamese crocodiles share a common stomach and yet struggle for food. Semantically, fun means stomach while funtum means ‘put together’ or ‘mixed together’. Funtum also represents the rubber tree that produces a milky sticky substance used to glue items together. Fu-ne-fu (literally, ‘stomach and stomach’) represents two stomachs joined together. Dԑnkyԑm is crocodile. Dԑnkyԑmfunefu, therefore, means ‘two crocodiles with stomachs joined together’. On the other hand, funtum, as verb, also means ‘to stir something up with tension’, generally producing dust. This also draws attention to the struggle or the confusion that comes with the two crocodiles struggling to feed.

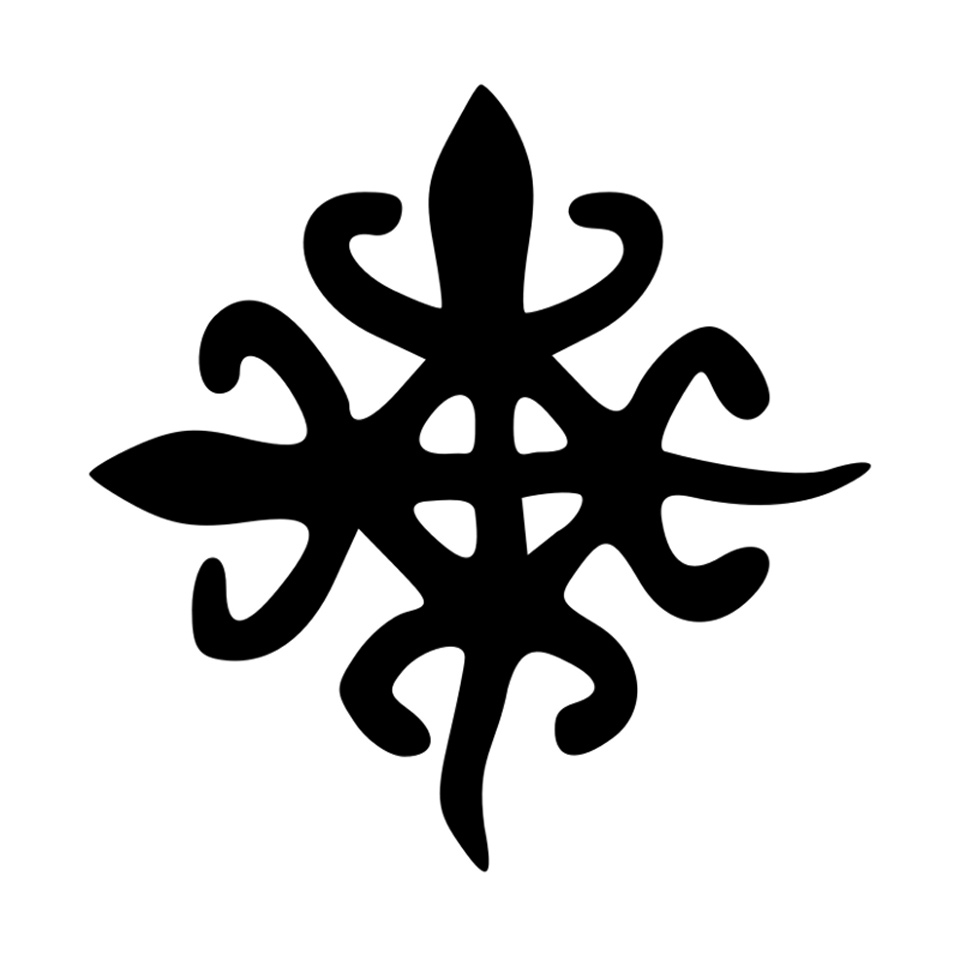

Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol (Photo: the author)

The Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol (see Figure above), is a graphical representation of two crocodiles rendered in silhouette in a perpendicular orientation with a conjoined and centred stomach, which is a common food receptacle. There are four juxtaposed arc-like lines interspersed and connected by four diagonal lines, creating a rhombic shape at the centre of the symbol. The four arc-shaped lines suggest the limbs, with the prominent sharp-tapered edges attached to the forelimbs placing emphasis on the cephalic regions. At a casual glance, the idealised limbs appear to be same in size, yet a close observation reveals that the forelimbs slightly outsize the hindlimbs. Two tadpole-shaped linearity with sharp-tapered edges placed perpendicularly to fuse with the limbs give a heightened impression of two reptile figures put together.

The Akan expression fun, which is the stomach in the case of the Siamese crocodiles, has two levels of meaning in Akan worldview, the superficial and the hidden. The Siamese crocodiles have a common stomach yet the two heads scramble for food. Each tongue yearns to have a taste of the food, though the gulps of food consumed by each enter a common receptacle. The complexity of this allegorical image could also be found in its multifaceted cultural interpretations.

Criteria for Selection (Educational Relevance & Quality)

The Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol belongs to the family of Adinkra symbols. The symbols encapsulate the general Ghanaian philosophical thoughts and ideologies, cultural values, beliefs and practices. Its origin and first usage is traced to the Asante nation state, which is part of present day Ghana (Rattary, 1927). Its usage predates the 19th century as recorded by Bowdich (1819).

The multi-layered meaning of the Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol tells its usefulness and educational relevance in the Ghanaian society. Due to its historical, socio-cultural and national importance in Ghana, Adinkra features in the design of decorative and functional artworks. The Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol designed into carved wooden stool symbolises unity in diversity, democracy, shared destiny and female-male duality. Giving visual annotation to the idea of unity in diversity, the compositional structure of the Funtumfunefu-Dԑnkyԑmfunefu symbol shows formidable stability, an attribute of unity. There is deliberate inflation of emphasis depicted by the prominent sharp tapered edges attached to the forelimbs, which connotes power, energy and aggressiveness in the process of scrambling for ‘food’ by the Siamese crocodile. Viewers who do not understand the true symbolism of the image sometimes greet the aggressive depiction and the centred common stomach with negative interpretation. However, in the same stable composition, the graceful movement that bedews the tadpole-shaped figures placed at right-angled position creates an impression of diversity.

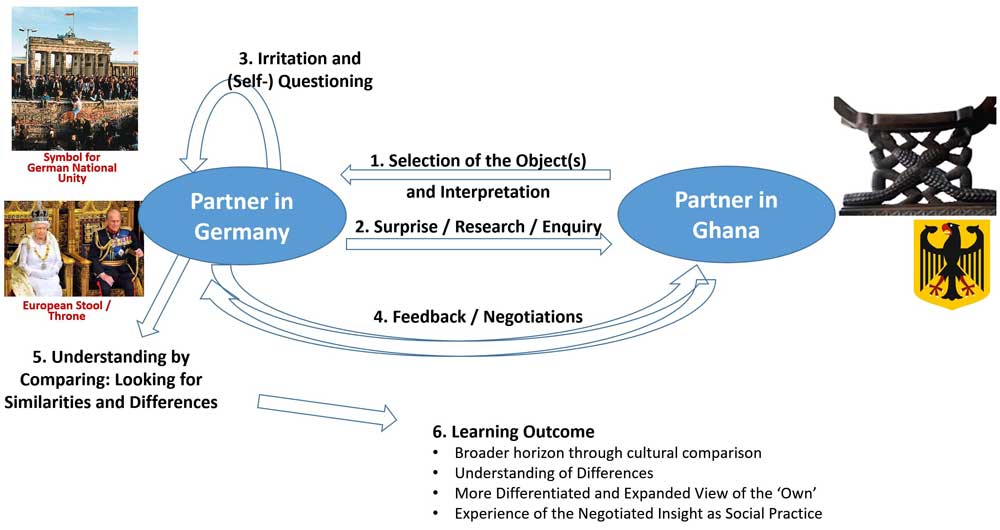

Methods/Interpretation/Research Questions

The asԑsԑgua (stool) in Ghana symbolises the soul of the society and serves as inoffensive symbolic link between the people or the subjects and their head of state or king (Antubam, 1963). It implies that the stool has both political and nationalistic useful to the citizenry and their ruler. In this instance, the stool reminds its users and observers of the need to engage in activities that will lead to unity rather than divisive tendencies. It teaches the Ghanaian society of shared destiny and the need to strive for oneness irrespective of one’s political affiliation, social standing, physique or race. The integration of the Funtufunefu Denkyemfunefu symbol into the political significations of stool symbolism therefore combines the essence of communal leaving and nationalistic feeling with power and governance. Just as the Funtufunefu Denkyemfunefu stool symbolises unity in diversity, and nationalism, the coat of arms of Germany also symbolises national unity. In this sense, both are thematised on unity and national consciousness. Both designs are abstracted animal figures and play allegorical role in the semiotic interpretations of the symbols.

The coat of arms of Germany

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bundeswappen_Deutschlands [28.010.24]

In terms of artistic presentation, both were rendered in silhouette. The Funtufunefu Denkyemfunefu stool gives expressive meaning to unity by underscoring that individual difference, diverse shades of opinions and social standing that usually operate in the search for unity but must end in oneness of purpose for the national good. The broad vertical lines that conjoin the flanked arc-shaped lines to give impression of the wings of the eagle figure suggest strength, power and authority of the Germany coat of arms (Figure 3).

The common symbolic ideology in both the Germany coat of arms and the Funtufunefu Denkyemfunefu stool is to strive for oneness. Exploring the design concepts, socio-cultural and identity connections between these two images create opportunities for new levels of greater bilateral understanding and integration.

Obviously, interrogating images of this nature and identifying their essence within their traditional setting vis-à-vis other cultures is likely to help to eliminate prejudices about visual cultures among nations and reduce the barriers in visual communication.

References

- Amenuke, S. K., Dogbe, B. K., Asare, F. D. K., Ayiku, R. K., & Baffoe, A. (1991). General

- knowledge in art for senior secondary schools. London: Evans Brothers Ltd.

- Antubam, K. (1963). Ghana’s heritage of culture. Leipzag: Koehler & Amelang.

- Bowdich, T. E. (1819). Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. London: Cass.doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107444621.

- Essel, O. Q. (2019). Dress fashion politics in Ghanaian presidential inauguration ceremonies from 1960 to 2017. Fashion and Textiles Review, 1(3), 35-55.

- Rattary, R. S. (1927). Religion and art in Ashanti. . London: Oxford University Press.

published March 2020