A helplessly wretched female figure: The “Little Mermaid” in Copenhagen

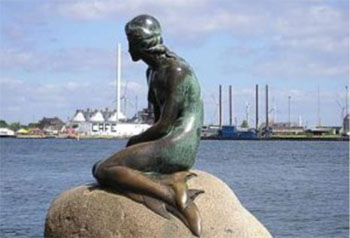

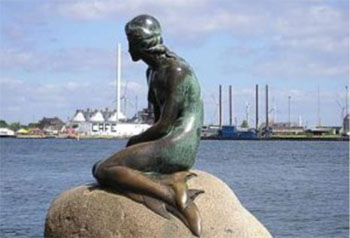

Well known worldwide is the monument of the „Little Mermaid“ in Copenhagen. The figure is called a “national symbol” for Denmark and a “landmark” for Northern Europe. The bronze sculpture of 125 cm height was constructed by Edward Eriksen in 1913. It shows a naked young woman, her feet like the tail of a fish. The intention of the sculptor was to honour and remember Hans-Christian Andersen (1805-1875), the Danish author of the story „Den lille Havfrue“ (The little mermaid). The place which had been chosen for erecting the monument is a rock in the water near the open sea; the figure turns her face to the shore of the Danish capital Copenhagen.

"Little mermaid" by Edward Eriksen 1913, 125 cm, Copenhagen harbour,

https://dreamguides.edreams.de/daenemark/kopenhagen/die-kleine-meerjungfrau

With this installation the country accentuates its identity of being involved in the element water and its representation in literature and culture. The famous piece of art transports different messages and reactions, has its own life and a specific history.

The narrative behind this figure, a fairy-tale for children, is well-known in Europe: A young mermaid wants to get into contact with a prince she loves. But he never recognizes her and marries a noble woman. The mermaid dissolves to foam, which flows back in the ocean. But also she is transformed to stay as a ghost in the air, where she can be part of earthly life and earn an immortal soul.

As a being of the nature the mermaid is part of the “other” of civilization and as subordinated to human and especially masculine beings. The title marks her to be “little”, not having a name and individuality. She did not receive any respect and interest, not even for her female beauty. By this ignorance she is killed, with no traces of her life. The story shows the most helplessly wretched female figure in literature we can imagine.

Within a memory-culture the monument might help a region of seafarers to feel superior over the sea and the beings involved with this element. Denmark was a colonial power. From overseas came goods and wealth on trading-ships. People from West Africa were deported as slaves to the Danish colonies Carribean Islands, where they had to grow sugarcane. The Molasses, the essence of this plant, was brought to Northern Europe, where Rum was made from it, the central product which made towns very prosperous. In visualizing a sentimental mythical story from the period Biedermeier the monument helps to divert from this context or even to suppress it. But the symbolic meaning might also be an accusation against (male) neglection of the nature and a warning for girls to hope to win the dream prince. It also can be seen as a protest against monarchy, aristocratic lifestyle and the glorified royal history of the country.

Performance and public reactions

Many tourists visit the monument every day and there are activities and actions around it. It stimulates the wish of giving the mermaid the attention she did not get in the story, as a symbolic compensation. There are also anonymous acts of aggression and destruction against the statue (see examples). Feminist groups protest against the offer of a voyeuristic view on a naked woman in this exposed location, this is also done by conservative circles in a prudish mentality. The statue also provoked campaigns of environmentalists who added her slogans demanding protection of other creatures being under control of human power like the whales for example.

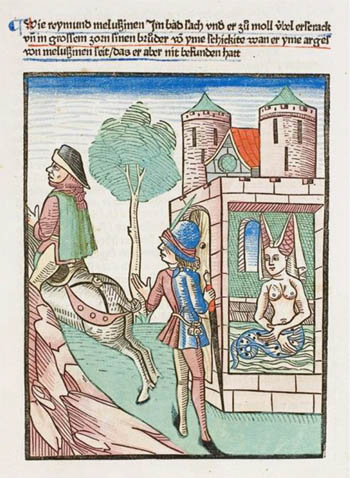

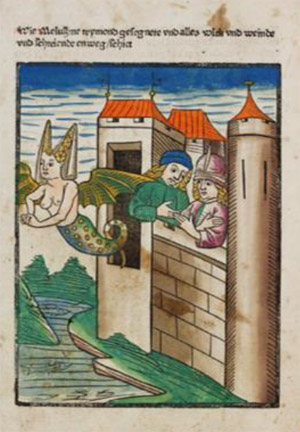

An independent queen in Premodern Times: Melusine

The fairytale of Andersen is a modern adaptation of older stories and there are lots of distinctions within the development of this symbolic figure. Very common throughout several European languages is a narration about a female figure with the name Melusine, which is derived from the french word “mere” (mother) of the Lusignans, an influencial family, living in France and in Cyprus, from where the legend might have reached Africa. In the shape of a woman she marries a nobleman and rules over the country, building it up in an innovative way. When her husband discovers her in the bathroom being half a dragon, she flies away. In the official belief she is said to be a dangerous demon with no soul, destroying Christian families. But in aristocratic traditions the mermaid is understood as the ancestress of their gender and put in their heraldry. In illustrations in books she is depicted as a courtly lady with half the body of a fish, standing in a basin; the destructive element of water being abolished. She is not a victim, but the active part in the plot; when she leaves, her big family suffers and the country loses its strong ruler with her outstanding creativity.

The twofold character of Melusine represents very well the beginnings of noble families: Polygamic life was common, and when the institution of the Christian marriage was imposed, one of the spouses of a ruler needed to be sent away. The element water might hint at the origin of the mistress from a village near the river outside the castle, which is on top of a hill. In popular narrations she was given an aura of mystery, having the body of a dangerous monster.

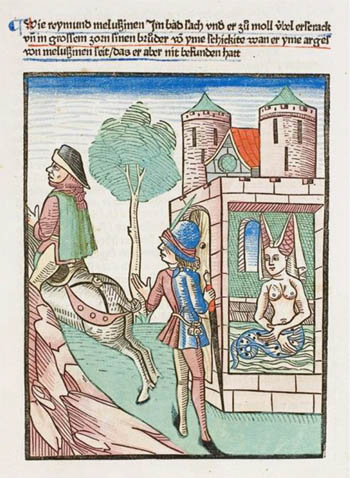

Melusine. The mermaid as a court lady and the ancestress of noble families (woodcut and illustration of a manuscript 15th century), Thüring von Ringoltingen: “Melusine”. In der Fassung des Buchs der Liebe (1587), hg. Hans-Gert Roloff, Reclam Verlag Stuttgart1991, S. 3.

She is discovered having half a fish-body (book illustration 15th century), Thüring von Ringoltingen: „Melusine“ First printing Basel: Richel, around 1473/74. digit. ULB Darmstadt urn:nbn:de:tuda-tudigit-35087

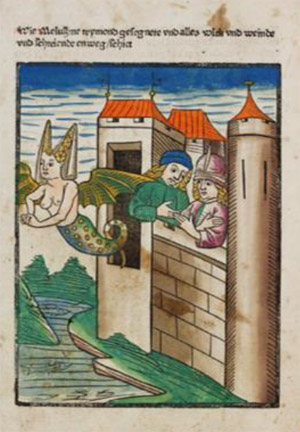

She flies away (book illustration), from "der Seelen Wurzgarten“. St. Peter pap. 23, Coburg bei Schwäbisch Hall 1467 (digitized by the ‘Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe’, 65v.)

The modern tale of a beauty killing her lover: Undine

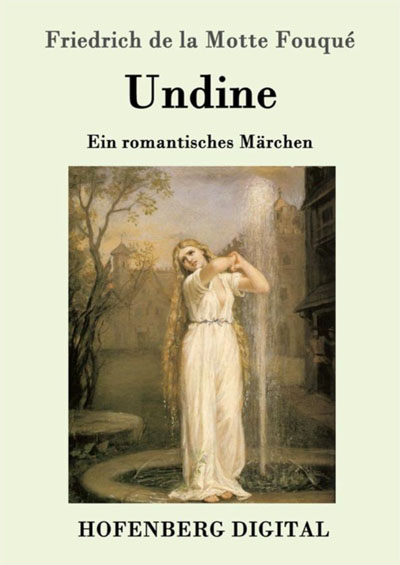

With the name “Undine” (lat. “unda”: wave) in Romanticism the mermaid-figure develops vampiric qualities, killing her lover by a kiss when he marries another woman.

This motif inspired many paintings. They channel phantasies and visions about the chances and problems of a partnership between persons from different origin and about death as the consequence of an unsuccessful encounter. How can strange-looking persons, which come from or over the sea, be integrated?

Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué (1777 – 1843), novel, 1814, published by Karl-Maria Guth. Berlin 2015, Painting by John William Waterhouse 1872.

Conclusion

Premodern times reflect the mermaid mainly as bringing fertility from nature to mankind, hoping to gain a soul through marriage with a human being. There are systematic changes to this story during modernity, which might result from the background of colonialism as absorption and subjugation of everything different and “strange”. Men are longing for its attractiviness, but also fearing that this inclusion of a natural being might cause protest and fury. The European tradition can be said to be a parable about migration and exchange between different worlds, the mermaid being a symbol-figure for the futile attempt of colonizing the other.

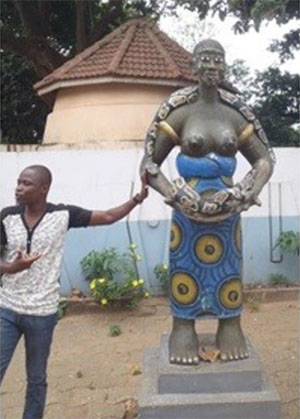

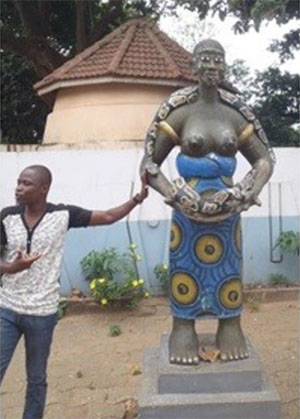

The task of a transcultural comparison: Mami Wata

In Ghana I learned about Mami Wata, a traditional African figure, the patron of fishermen. In Quidah (Benin) I saw her as a goddess of the python, the holy snake. She has her own shrine where specifically educated priests pay tribute to her to keep her merciful. The name is interpreted to be a pidgin-version of „Mother of the water“. Scholars from Europe assumed that Melusine was carried on ships' bows in the 15. century from Europe to the West-African coast, where her narrative interlaced with local narrations with their own long tradition of water-goddesses. But: It might also be the other way round, from West-Africa to Europe, probably on the trade-roads through the Sahara. There, the legend emerged much earlier and arrived in Europe as early as the 12th century, when the mermaid-stories began to gain popularity. How is a figure transformed when it is transferred to a region with such different history and traditions?

Temple of the Python, “Holy Forest”, Quidah (Benin) 2015 Foto: Nina Paarmann

Fishing boat in Winneba (Ghana) 2012, Foto: Nina Paarmann

Quidah (Benin) 2015: “Slave Road”, Text: “memorial for the ‘tree of forgetting’ which had to be orbited, nine times by the male and seven times by the female slaves”, Foto: Nina Paarmann

References

- Hans-Christian Andersen: „Den lille havfrue“ (The little Mermaid) fairytale, in: Sämtliche Märchen 1-2, München 1974 (hg. Nielsen, E.).

- Bea Lundt: Melusine und Merlin im Mittelalter. Modelle und Entwürfe weiblicher Existenz im Beziehungsdiskurs der Geschlechter. Ein Beitrag zur Historischen Erzählforschung. (Diss. 1990), Fink-Verlag München 1991.

- Bea Lundt: Wassergeister als universales Motiv. Paracelsus’ Deutung der Nymphengestalt und die Figur Mami Wata in Afrika. In: Nova Acta Paracelsica. Beiträge zur Paracelsus-Forschung (NF 28). Hg. Pia Holenstein Weidmann. Bern u.a. 2018, S. 9-40

Edited by Kelly Thompson.

published February 2020