The Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Sydney Opera House, the Empire State Building in New York – it is not uncommon for innovative and striking buildings to become symbols of the cities they were built in. Architectural landmarks turn into trademarks of their cities. They shape the city’s silhouette and make it recognizeable.

In Munich, a big city in the South of Germany and provincial capital of Bavaria, one of the most striking buildings is the Frauenkirche, which loosely translates to “Church of Our Lady”. It is dedicated to Virgin Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, who plays a big role in Munich as she is said to be the patroness of Bavaria. Its 99 meter (324 ft) high twin towers with the characteristic cupola roofs rise high over the inner city (as it is still prohibited to build any higher than them within the inner city). It is - by all means - not the biggest or even most beautiful church of its kind. Neither is its location in the city center, on plane ground and narrowly surrounded by pubs, shops and historic residential houses, spectacular.

Up to this day, the Frauenkirche is the tallest building in Munich's inner city. View from the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich ©the author

Up to this day, the Frauenkirche is the tallest building in Munich's inner city. View from the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich ©the author

Still: The citizens of Munich have great sympathy with the brick building and identify strongly with it. There are several reasons for that: First of all, about 30% of the people living in Munich identify as roman catholic Christians and therefore have a religious connection to the 500-year-old church that is still in use for almost daily services. But the number of Catholics decreased drastically since 1925, when more than 80% identified as Catholic. In conclusion, there must be other reasons why this church is so important for Munich.

A people’s church

What makes this church indeed quite unique is the way it came to be: Munich didn’t lack any churches at all. In 1468, when the construction of the Frauenkirche was started, only 13,000 people resided there and there already was (and still is) a cathedral in the city center: Saint Peter’s church, or simply: Alter Peter (Old Peter). The Frauenkirche was enormously large compared to the city’s size and can house 20,000 standing people. It was built within only 20 years, which is faster than any other church in Europe at that time. The construction was probably initiated by the citizens – and can therefore be seen as a sign of confidence and emancipation of the common people in regard to the ruling class. (Which makes it all the more tragic that the towers were abused early on as platforms for cannons during the Landshuter Erbfolgekrieg at the beginning of 16th century, a war between two aristocratic families contending for heritage.) As a side note, Germany’s supposedly very first photography, taken in 1839, shows the twin towers of the Munich church.

Muslim towers on a German church?

The two cupola roofs made of oxidized copper give the cathedral its unique and unmistakeable shape. Originally, it was meant to be topped by gothic pinnacles (comparable to those of the cathedral in Cologne, Germany). But at the beginning of 16th century, architectural (and overall artistic) style changed drastically with the advent of the Italian renaissance. Pointed church spires suddenly seemed old-fashioned. And so, for more than 30 years, the two towers of the Frauenkirche remained “headless”.

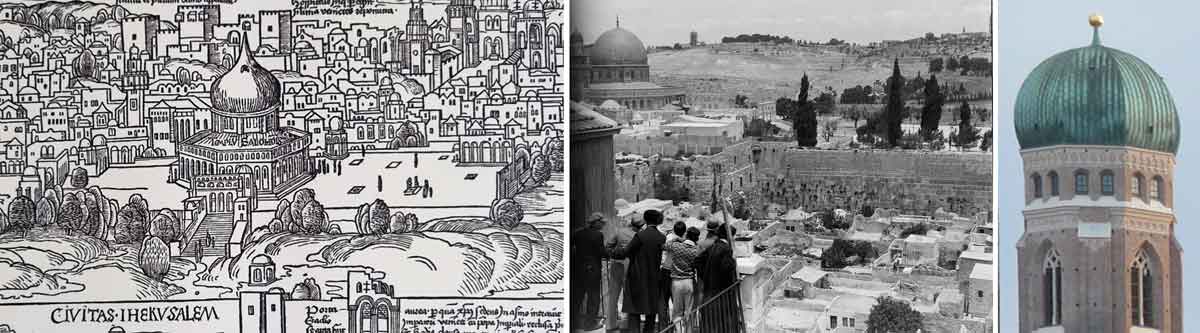

Bernhard von Breydenbach, Peregrinatio in terram sanctam, 1486, woodcut (Creative Commons); The Temple area, 1920, Library of Congress; Blick auf die Türme der Frauenkirche vom Odeonsplatz aus. 2017, D. Fuchsberger (Creative Commons)

Lukas Rottaler, who was assigned with the construction of the roofs, was long thought to be inspired by Venetian churches, precisely the cathedral Madonna dell’Orto. Indeed, the 14th century Italian church has a high brick tower with a cupola roof that might look a little like the Frauenkirche, if you turn a blind eye. But the origins of the onion-like shape are assumed to reach way back and way farther: Rottaler probably saw a woodcut of Jerusalem, which shows the Dome of the Rock. This dome, erected in the 7th century and therefore the oldest edifice of the Islamic world, marks a place that is equally important for Muslims, Christians and Jews – the dome itself though is Muslim. That didn’t keep Rottaler from taking inspiration from the Dome of the Rock for his building project at a Catholic church in Munich. Hence, the Frauenkirche is shaped by originally “oriental” roof tops.

Moreover, many churches in the rural outskirts of Munich, which were built in the following centuries, are oftentimes crowned by bulbous cupola roofs. This drop shape, which contrasts the villages’ common saddle roofs, now naturally is a part of the landscape as well as of the baroque style.

The devil, a Munich sense of humor, kitsch, tourism and modern lifestyle

One more reason why the Frauenkirche is so important for the Munich identity are the many legends surrounding it, which are an inherent part of many children's upbringings. The story of the bet between the devil and the constructor of the church, master bricklayer Jörg Ganghofer is widely known among Munich citizens. Ganghofer bet his soul that in this church there would be no windows. As soon as the church was complete, the devil entered the back of the church through the main portal and looked around. Indeed – there were no windows visible! Of course, the church has big windows which let an even stream of light enter the gigantic room. Ganghofer skillfully placed the massive pillars framing the middle section of the nave so that they cover all windows from a certain point of view – and thus won the bet! The devil was outraged and stomped his foot on the ground. This footprint is still visible in floor tiles (image below). In his temper, lucifer left in a rush, which caused a chilly gust of wind that up to this day blows around the church.

The "Devil's footprint" ©the author

There are many more legends like these surrounding the historical center of Munich. The fact that they are not forgotten but very much part of social life shows how much the people of Munich value their ancient traditions and customs. Also, these legends – and the legend about Jörg Ganghofer is a prime example for that – often showcase a certain sense of humor, mischievousness and boldness. Possibly typically Munich qualities.

The unique twin towers as logo: A design for a Munich tourism agency ©Georg Schatz, schatzdesign.de

Today corporate logos, kitschy souvenirs but also everyday products reference the Frauenkirche’s silhouette. The Munich tourism agency „München Tourismus“ markets the city with the slogan “simply Munich”: approachable, hospitable, relaxed. It’s all about “Genusskultur, Kulturgenuss”, which translates to „culture of enjoyment, enjoyment of culture”. According to the agency, tranquility, love for old things and the so called “Bavarian cosiness” are trademarks of the Munich way of life. Compared to the daringness of Lukas Rottaler and Jörg Ganghofer, the constructors of Munich’s biggest cathedral, these qualities seem rather tame.

References:

- Forschungsgruppe Weltanschauungen in Deutschland: „München: Religionszugehörigkeiten 1925-2018“, https://fowid.de/meldung/muenchen-religionszugehoerigkeiten-1925-2018

- E. Wagner, S. Wimmer, L. Sedghi: Isar-Arabesken – Spuren des Orients in München, München (Alitera), 2013

- https://stadtfuehrung.info/stadtfuehrungen/zeitreise_muenchen_anhand_alter_fotos_und_bilder

- https://www.muenchen.travel/artikel/ueber-uns/die-marke-muenchen

- https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Frauenkirche,_M%C3%BCnchen#Der_Neubau_im_15._Jahrhundert

- https://www.venediginformationen.eu/kirchen/kirchen-in-venedig-teil-3/madonna-dellorto/madonna-dellorto.htm

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tempelberg#Islamische_Bebauung:_al-Masdschid_al-Aqsa

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frauenkirche_(M%C3%BCnchen)#Bau_der_sp%C3%A4tgotischen_Kirche

published November 2020

Up to this day, the Frauenkirche is the tallest building in Munich's inner city. View from the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich ©the author

Up to this day, the Frauenkirche is the tallest building in Munich's inner city. View from the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich ©the author