Silent Protest through Everyday Objects

Clive Pillay Women educating for change 1990, fabric (collection of the author)

T-shirts are comfortable and practical as everyday wear and serves as a statement attire when inscribed with a message. A message on a t-shirt associates an individual with a particular brand of music, movie character or a social commitment. However, when t-shirts are worn at political rallies, these are branded with a particular colour and visual image that become the first interface of communication announcing resistance.

The ideology of Apartheid in South Africa was an institutionalised system that divided and governed its black majority and white minority population along racial lines. The atrocities endured by black African people resulted in the formation of various political organisations that were opposed to Apartheid. Different strategies were initiated to combat Apartheid both nationally and internationally that served specific purposes. For example, during the 1980s, there was a stronger call for a cultural boycott against South Africa by the United Nations General Assembly, and the South African government’s response was to censor ‘political’ artwork, writing, posters, photographs, records and tapes, declaring them to be weapons of war and an incitement to violence against the state. This censorship was an indication that cultural expression played a significant role during Apartheid.

“Where there is power, there is resistance” (Foucault, 1978) succinctly explains the Apartheid situation. The slogan, ‘Culture as a weapon of the struggle’ was officially adopted as a strategy by anti-Apartheid organisations at the Culture and Resistance Conference and Festival (1982) hosted in Botswana. The statement, “Where there is resistance, there is power” by Lila Abu-Lughod (1990) reconsiders the power relationships inherent in resistance. For example, the sight of thousands of t-shirt clad protestors wearing the same or similar printed image of protest, creates a powerful collective tool of defiance. Such action can be liken to protests in Hong Kong (2019) and France (2019), where the black umbrella and yellow vests were used as symbols of protest, respectively. In both cases, the use of a collective colour signified both the protest and the momentum of defiance. This also means that the collective tool of resistance becomes something separate from the individual.

An individual wearing a t-shirt outside of a march can be considered as practicing an ‘everyday resistance’. This term was introduced by James Scott (1985) in its application to non-political forms of resistance. The repetition of an ‘everyday resistance’ has an impact that is not always noticeable. In wearing a ‘struggle’ t-shirt the practice becomes an embodied representation of resistance as it personalises the stand and serves as a ‘weapon’ against authority with its visual language and text that always accompanies an image.

Clive Pillay Women educating for change 1990, fabric (collection of the author)

This t-shirt was printed for female educators who were members of the Durban (Kwa Zulu Natal) branch of the South African Democratic Teachers Union (SADTU). The image directly speaks of women’s involvement in the struggle, using education as a vehicle towards change. The struggle itself is represented by the clenched fist (symbol of defiance) which takes up almost half of the image space highlighting the power of defiance, holding a pen and pencil. The image of a book and a stick of chalk appear secondary to the act of defiance, Defiance within the education sector has its own history and the stylised, simplified black image of hands and educational tools against a yellow background becomes a powerful image of resistance.

The image of the hands suggesting education and change also indicates a sharp contrast between the stylized delicate hands of women and the clenched fist. There is an awkwardness in the way the book and chalk are held as opposed to the confidence and surety shown in the clenched fist. The colours used in this print, red, yellow and black are also colours of the United Democratic Front’s (UDF) flag, a political organisation launched in 1983 which was affiliated to the African National Congress (ANC). This infers an indirect association between SADTU, UDF and ANC.

The word ‘Women’ states the position of the protest, a protest by women. This is a gendered position. Women faced a triple oppression of race, class and gender under Apartheid. Black African women did not have a political voice, as per Apartheid legislation. Often single parents, black women were considered as minors (children) during Apartheid which meant that they could not own property or take decisions which affected them and their families directly. The image also highlighted the separatist, specific, inferior poorly funded education that was offered to black learners. An education for black people was predominantly as labourers (farms, mines and domestic workers) restricted to specific career choices and institutions of learning.

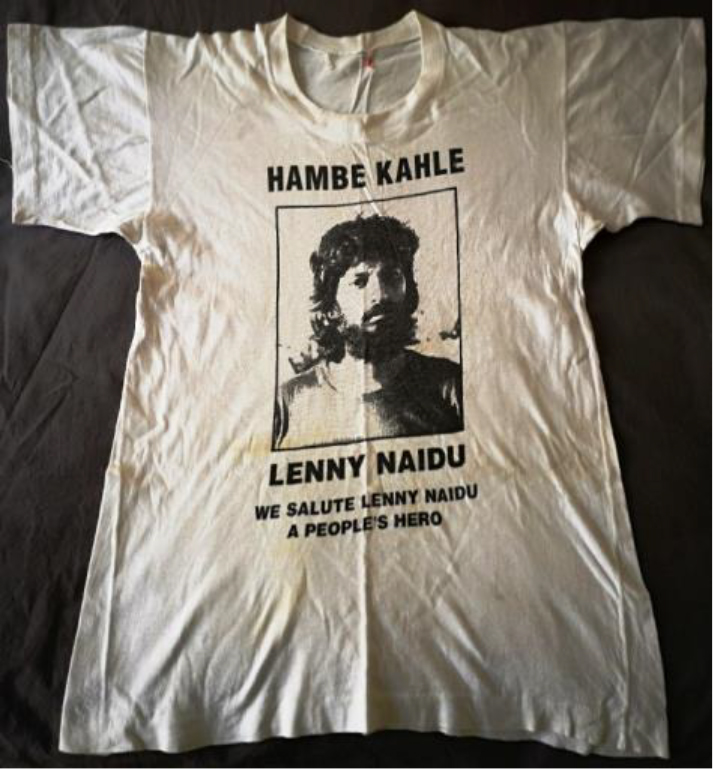

Clive Pillay Hambe Kahle Lenny Naidu 1989, fabric (collection of the author)

This t-shirt Hambe Kahle [Go Well] Lenny Naidu was printed in memory of a comrade who died at the hands of the Apartheid government. The image pays homage to someone who would have been targeted as a communist and therefore killed, apart from the fact that he belonged to Mkhonto we Sizwe [spear of the nation] (MK), the military wing of the ANC. To revere someone of this calibre as a hero would immediately incite revulsion and anger in people opposed to the ANC, the police and government officials.

It required courage to wear a T-shirt with such an image on your chest as it would have attracted attention when worn outside of a protest march. Such an act can be read as an individual protest of defiance as one’s identity is not camouflaged within a collective mass protest. It draws attention to the visual image associating the individual wearing the t-shirt with a particular act of resistance - in this case a supporter of violent acts and a revolution that undermined the Apartheid government.

Saluting someone is associated with war and soldiers, acknowledging that individual as someone who had committed an act of bravery, a hero. The difference is that this ‘soldier’ is in civilian not in military dress with long hair and a beard, unlike traditional army soldiers. The threat of ordinary civilians being ‘soldiers’ posed an even greater threat to Apartheid as they were not identifiable.

In my reading, these two images clearly become sites of embodied resistance. These are images that are powerful, instant messages of defiance against Apartheid. These t-shirts act as an alternative platform and strategy of resistance believed to have the potential for political and social change similar to radio, newspapers and graffiti.

Resistance is a reaction against a power that often elicits violence. Anti-Apartheid organisations in South Africa reacted against racial discrimination that resulted in violent responses from the police and army as well as arrests and banning of such organisations. Various strategies were implemented to draw attention to Apartheid atrocities that included the wearing of t-shirts with images denoting protest and resistance. Wearing such a t-shirt suggests an embodied, individual response of protest as well as a collective message when seen together in mass demonstrations. When used as objects of protest, t-shirts became public announcements of dissatisfaction against Apartheid.

published in March 2020

References

- Abu-Lughod, L. (1990). The Romance of Resistance. Tracing transformations of Power through Bedouin Women. American Ethnologist, 17(1), 41-55

- Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1: An Introduction. New York: Random House.

- Pearson, D. (1986). Taking the art out of apartheid. New Musical Express 28 June,11.

- Scott, J. C. (1985). Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of resistance. London, Yale University Press.

- Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2005). Some Intellectual Genealogies for the Concept of Everyday Resistance. American Anthropologist, 107(3), 346-355

- Vinthagen, S. & Johansson, A. (2013). Everyday Resistance: Exploration of a concept or its theories Resistance Studies magazine, 1(1), 1-46