Transnational Student Collaboration

Octavia Roodt, South Africa & Stela Vula, Germany at Digital Art Space

Octavia Roodt and I became acquainted on the on 12th of July 2020, when we exchanged our first email. I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich at the time, while Octavia was finishing her master’s studies at the University of Pretoria. Over the course of several months, we worked on the “transculturality” project, a part of the field of art didactics led by Professor Dr. Ernst Wagner in Munich. Octavia and I began our exchange with a spirit of experimentation and fluidity. Led by our unique set of differences and commonalities, we discussed many possible areas of artistic collaboration. We shared personal stories and were able to identify domains of common interest. Beyond personal formation and family history, we were also interested in gender issues, national identity, language, education, religion, political systems and the evidence of these abstract social structures in our daily life. I moved to Germany from Greece and have been living in Munich for the last 8 years. I finished my studies in the field of sculpture and then in the field of art education. For the last few years, I have been producing hybrid artworks. These works consist of both physical and digital materials. In my practice, I use space mapping techniques, light, colour and user interactivity (the latter triggered by custom software). My work often explores and deconstructs well-established, symbolically connoted aesthetical manifestations of my everyday life. This is accomplished through the use of symbols, iconography, tradition, rituals, emblems, institutions and so on.

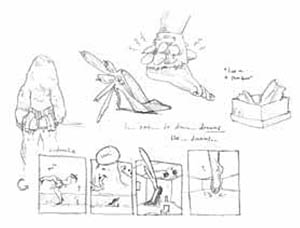

Octavia is a South African artist. She has been studying at the University of Pretoria for the last 7 years, completing studies in graphic design before shifting to fine art in her postgraduate studies. She creates narratives by drawing characters in interaction with personal and global symbols. This means that she draws archetypal symbols that interrupt, expand on or enrich her autobiographical stories. Her approach merges academic sketching, narrative strategies and poetry. She works on paper and often completes her drawings digitally. Octavia and I employ two genuinely different artistic languages, which generate a variety of materials, strategies and realization techniques when working together. Our field of interest kept expanding exponentially. The excitement of attempting to combine our different approaches to storytelling in a single work, underpinned by a desire to maintain our individuality,

lead us to holding regular meetings. These meetings served to update and freshen the conversation, as well as providing a space to reflect on our practical work. To begin, we decided to work with narrative structures. We would exchange personal stories and attempt to translate the other’s story into artistic expression. Our translation became a way to explore our sense of identity and larger societal structures. We wanted to see how representative or authentic our stories could be. What kind of patterns can they produce, and how? Speaking generally, what are the specific roles that define our own perception?

Octavia and I officially began to work with narratives and our personal structures upon exchanging our first story. We set specific criteria for the stories. The stories should be relatively short and should be inspired by our everyday life and real experiences. The stories should also trigger identity processes that may be explored when experiencing the artwork. Our intention was to create a work which would combine and integrate our two artistic languages in a dialogue. We decided that this dialogue should take place during the different phases of the artistic process; from the beginning of an idea, through to the means of construction and materials being used and ending in the exhibition space and public communication.

The experimental nature of this exchange, as a “test driven development” process, has its own challenges. It demanded a lengthy phase of exploring and designing, a careful consideration of results and investigation of the actual visible and tangible artwork. After commencing with the telling of stories, it took us approximately 6 months of “back and forth” to see which direction should be followed.

Octavia sent me her story on the 17th of July and started working with drawings on my story in the next few days.

Reading my story provided Octavia with an opportunity to explore a new set of symbols. Other material brings a fresh perspective, without losing the intimacy that personal stories are capable of. My story formed as a dream world in Octavia’s mind.

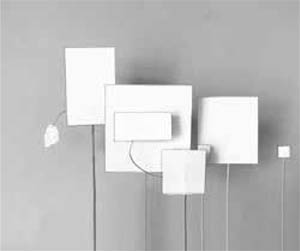

For Octavia’s story, I used a projection surface; a combination of glass (height: 4 meter, length: 4 meter) and solid building material (height: 3 meter, length: 4 meter). The projections included animated symbols and repetitions. I converted Octavia’s text into a video installation that suggest the characters, patterns and musings, as well as its heroic-mythical dimensions.

The first two iterations highlighted the differences between us, as well as our particular creative strategies. Art was being produced in completely different ways. We decided that the two strategies retained too much of their singularity and subjectivity. At this point, we retained two vastly different perspectives, where the transcentive process had not yet taken place. Furthermore, the final experience of such an approach in a real exhibition space seemed overly complicated.

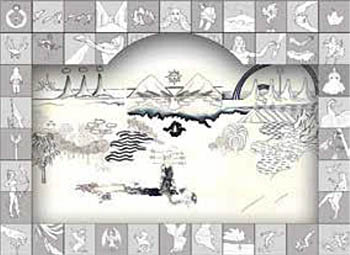

Octavia and I began to reflect on these issues during the next few meetings. Three months later, on the 18th of October 2020, I came up with the idea of using a 18th century lithographic print as a structural template and the basis of our future steps. The print, from William Hogarth’s Analysis of Beauty, 1753, had come up in conversation about Octavia’s Master’s

work. We decided to borrow some elements of the form and the composition of the template and “build” our narratives in a three-dimensional space. Furthermore, we decided to add another criterion; to work in the same material (drawings on paper, in black and white).

William Hogarth, Analysis of Beauty, Plate 1, 1753

We both found the narrative potential of the template exciting. It promised to bind our visual approaches together into one work and to contain the stories’ intermedial nature. In other words, it could cater to both stills and moving images. The template’s reference to art historical canon also became significant, in terms of exploring tradition and patterns.

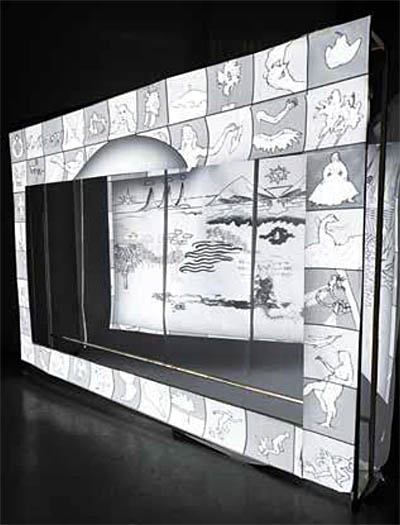

According to our new template, we decided that Octavia would create her work for the outer part of the model, and I for the inner part. I started with “The garden of delights” as a kind of blueprint or architecture for Octavia’s story, or the inner space of the work. I also designed and built a structure that could integrate the printed or projected border that Octavia made drawings for. By recreating the nature of the original painting, with icons of our social abstractions, I was creating a new cartography for Octavia’s story, a new horizon and a new land.

Although the result of this trial combines our two genuinely different artistic expressions, it excludes important elements and especially those that make the artists’ languages as different and unique. On the other hand, the analogue nature of the work had already begun to demand its own space and became engaging to the public. When images are projected, the viewer’s presence is pronounced as the light, shadows and the various spatial layers lures the public into the role of spectator. It resembles and acts like a theatre!

We aimed to take advantage of this newly evolved perspective and even play up the elements that associated our work with a theatre and theatrical scenes. We wanted to actively engage the public and have them create, delete or modify the scenes individually. In this manner, they would be able to control story fragments by creating new versions or translations of our original stories and intentions. Through simple ‘Drag & Drop’ functionality, as a method of exploring graphical interfaces, the public would have the possibility to recompose, replace and reconfigure the whole picture and its meaning.

To have our work be this “open”, to let others see in our world and construct it again according to their own intentions and ideas, became a mutual fascination. While one person could create a very loud and intensive version of our work, someone else could choose to leave the scene blank, without landscape or protagonists. Letting go of the total control and possession of the appearance of the artwork blunts the precision of your intentions and plans. Along with that, it disengages you from responsibility and consequence. Conversely, the artwork may also create new dynamics that could enable you to get a look into the spectator’s world, their tendencies and their habits. We could provide our eyes and our words as a platform, for them to see and

tell their own stories. If this were the case, Octavia and I could explore the socio-visual habits of those engaging with the theatre, while simultaneously providing the public with a ‘safe’ scene. Upon second though, however, this would not be safe at all. A theatre is characterized by abstraction and deception. Nevertheless, our lies are sometimes the only truth that we have.