Based on the Ghanaian interpretation, it quickly became clear that certain ideological or political positions are immediately connotated with the respective image selection. These in turn are linked to historical and social experiences, which Winkler (2021) recently elaborated on the basis of the history of Germany. In our case, the West German, left-liberal intellectual milieu is of particular interest, since all the German project partners involved in the discussion can probably be assigned to such a milieu. "In the 1970s, the view prevailed among liberal and left-wing intellectuals in former West German, which objectively was not a nation state, did well to see itself as a >post-national democracy<. In the 1980s, this led to the conviction among many that the time of the nation state had passed and that Europe only had a future as a post-national union. [...] The self-destruction of one's own nation-state [in Nazi Germany - author's note] led to the conclusion that the nation-state as such had outlived its usefulness, and the term ‘national’ was equated with nationalist. [...] In Germany the idea that the nations had to merge into a European republic found a broader public echo." (Winkler 2020 p.186)

For art educators, the majority of whom probably feel committed to this idea of Germany as a post-national democracy, the question of a current symbolisation of national unity[1] is therefore obsolete. It cannot therefore be relevant to art education. A consensus in the German team on how at least the general topic could be addressed could be reached by the proposal to deal with the topic on another level, and to use Hans Haacke's installation "Der Bevölkerung" (2000, courtyard of the German parliament in Berlin) to deal with the topic of "national unity" in a contemporary art lesson.

Hans Haacke (*1936) is a German-American artist who has lived and worked in New York since 1965 and whose conceptually influenced works primarily address art-political processes.

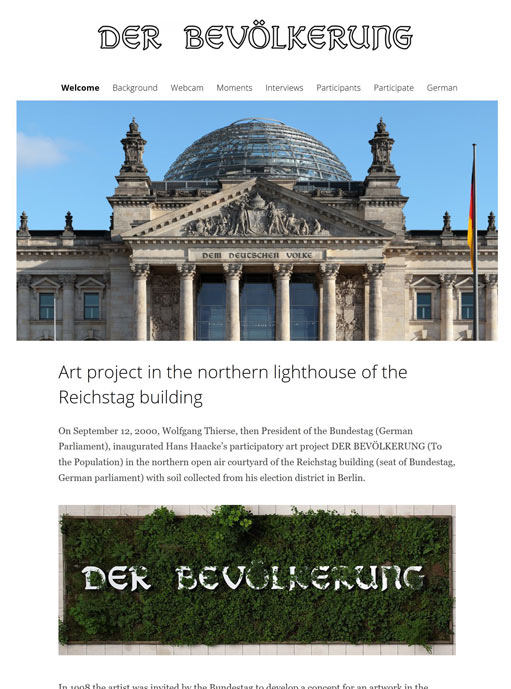

Figure 2: View into the courtyard of the Reichstag building. © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

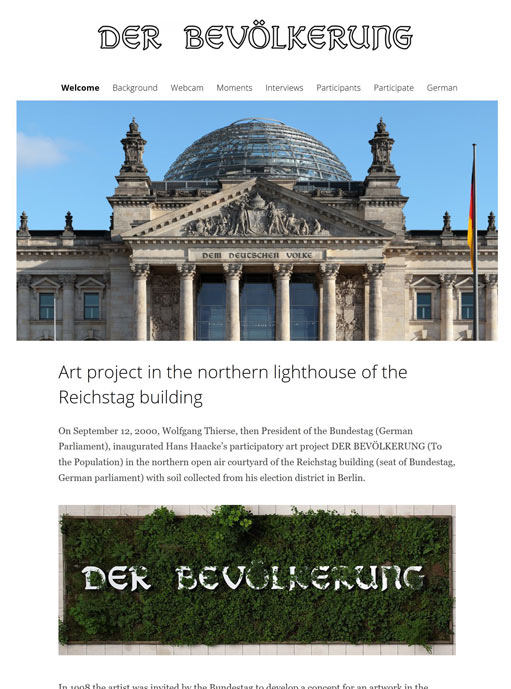

Haacke's installation "Der Bevölkerung" is located in a courtyard of the Reichstag building. This architectural context is part of the work. The building was constructed at the end of the 19th century, during the Second German Empire (1871-1918). In neo-baroque style, it paid homage to the national pomp under emperor Wilhelm II. Damaged by fire in 1933, it was further damaged during the Second World War. Located directly on the Wall to East Berlin, the dome was finally blown up in 1954. In reunified Germany, however, a new function was found for the building. Rebuilt according to plans by Norman Foster in the 1990s, it now serves the German parliament, the Bundestag.

Figure 3: View of the façade of the Reichstag building with the inscription "Dem Deutschen Volke" © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

Hans Haacke built a 21 x 7 metre rectangular, flat wooden enclosure in this building. He then asked the MPs to gradually fill it with soil from their respective home regions. In the middle of the box, the inscription "Der Bevölkerung" (To the People / Population) can be read, in white letters illuminated from the inside. The typeface corresponds to the inscription "Dem Deutschen Volke" (To the German People / Nation), which has been on the outside of the building's west portal since 1916.[2] According to the initiator, the invitation to bring soil from the constituencies is valid as long as members are democratically elected to the German parliament. A webcam, belonging to the installation (www.bundestag.de), takes a picture every day at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. and thus allows a take a look at the development of the project since 2000 and at the current situation.

Figure 4: An MP distributes the home soil from his constituency in Haacke's installation. © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst

When Haacke proposed to install this large-scale installation in the new parliament in 1999, ten years after German reunification, it triggered a heated public discussion. Many MPs found the words "Der Bevölkerung" (To the People / Population), which appeared to be a dedication, inappropriate and provocative. Haacke was deliberately alluding to the older inscription "Dem deutschen Volke" (To the German People / Nation) on the outer façade. In contrast to this, he used the term " Bevölkerung - population" to refer to all the inhabitants of Germany, including people who do not have German citizenship and live here. According to his own statement, Haacke was inspired by Bertolt Brecht when deciding on the lettering. Brecht had written in 1935 in exile that whoever said population instead of people would avoid many lies (Brecht 1935). Haacke is obviously also concerned with the question of how words can and should be used in the context of a national parliament to designate the basis of this democratically elected representation of the people/population. Does the term "Volk" fit, a traditional, conventional but loaded and perhaps not at all accurate term? Or would be the term "population" better, a word that sounds unfamiliar and strange at first, but perhaps makes more sense. The discussion intended on such questions is part of Haacke's work.

Similar discussions were triggered by the idea of having MPs bring home soil. For many, this was reminiscent of the National Socialist blood-and-soil ideology. Or they criticised it as "kitsch" because of the well-intentioned but overused symbolism. Obviously, the work here plays with this iconographic tradition (“Heimaterde”), but reinterprets it just as it reinterprets the lettering. At the same time, the installation is constantly changing as a result - both through the ever-changing soil and through the growth of the plants over the course of the year.

Figure 5: Screenshot of the project's website https://derbevoelkerung.de

© Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

The installation is thus in constant dialogue with the population designated in the inscription, tries to involve the MPs and responds as a living piece of nature to the stone surroundings of the parliament building. The work of art is thus never fully completed. Haacke's art project was particularly controversial in parliament; only by a narrow majority did the MPs finally vote in favour of the realisation of the artwork in 2000 after a specially scheduled debate in the Bundestag. The entire debate is documented on the project's website - as another part of the work (Bundestagsdeabtte 2021).

[1] I.e. a "small German" solution after 1990 and with shifted borders after 1945.

[2] It was designed by the Art Nouveau artist Peter Behrens.

References