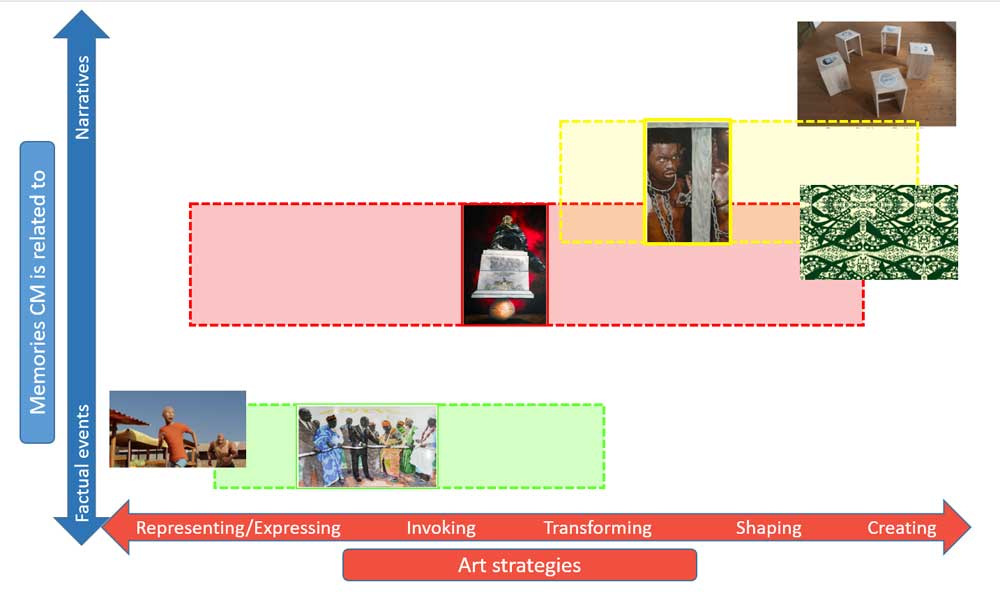

Placement of the works selected for the memory section, mapping them against the category of art strategies

All examples we discussed above show that collective memory always has a very high interpretative component, is always constructed – of course in various gradations. We have to reflect on this observation in the context of philosophical epistemology which postulates that a recognised object is always constructed by the observer himself through the process of recognition (Watzlawik, 1981). In the case of collective memory, we must then speak of a social construction. As visitors of the virtual exhibition, we can only perceive the perspective of the artists exhibiting here. This makes this aspect of constructed-ness particularly clear once again.

This understanding draws our attention to the producers of the interpretations and narratives, to the artists. They created the works. But what are they actually doing in their art? What strategies do they choose when it comes to such a challenging subject as collective memory? What is their approach? This will be briefly discussed in the last section, using the same examples as before.

David Ochieng, Soko Adventures: David Ochieng locates his idea of collective memory in an African market, focusing on a specific event (a chase) that can be perceived by anybody, perhaps any time. In dramatising the market event in digital animation, he concentrates entirely on the idea of expressing his understanding of everyday life in a condensed form. The artist thus selected a purely illustrative, almost mimetic strategy to visualise the subject and represent or express his interpretation of his own experience.

Dieudonné Assiga, L’unité: It is interesting to compare Dieudonné Assiga’s painting with images of the concrete event he is thematising, namely the ‘National Dialogue’ in Cameroon 2019, on the internet. Those images always show hundreds of people crowded together. The comparison makes Assiga's pictorial strategy clear: concentration on a few (ten) figures (in traditional and modern clothes), representing the different regions of Cameroon. Inventing a ritual (holding a ribbon together - something which did not take place) condenses the artist’s attempt to invoke his political ideals. This is emphasised through the bright yellow word UNITÉ at the top, slanted in perspective towards a distant point – the future. To bring his message across, he transforms the material (the photographs he found) into a pictorial language that allows him to add his viewpoint. In this way, the image becomes not just a representation of what happened but an evocation at the same time.

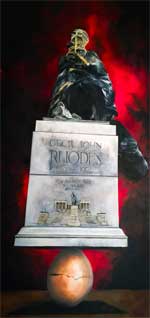

Tlotlo Sereisho, Rhodes Must Fall, a Mengelmoes: Tlotlo Sereisho chose an unexpected combination for the title of his painting. The part "Rhodes Must Fall" fits well within an exhibition about collective memory, as it refers to a historical event. But "a mengelmoes" (an Afrikaans word meaning hodgepodge) is rather uneasy. Through this word, the artist first of all names the surreal montage character of his work (balancing a monument on an egg), but he also introduces a linguistic mixture of English and Afrikaans. The consequence of his artistic strategy reveals itself in his own comment. He explains that he is using / appropriating the historical event to symbolically condense his daily experience of "still pending ... apartheid" and at the same time to agitate in the society ("exhortation") (Tlotlo Sereisho in his comment). To be consistent, he thus has to mix a broad range of different artistic strategies, more so than his colleagues discussed here in this chapter. From representation to creation: mengelmoes.

Gonca Sağlam, Polittalk: In her commentary on Polittalk, Gonca Sağlam speaks about "resistant rebellion against anti-democratic, autocratic to dictatorial governments”. But, what might this rebellion be in her work? If we take her suggestion (in her own comment) of "subversive strategies in an ironic and even cynical manner" seriously, it means putting our backsides on the faces of those in power. This ‘performative turn’ is an interesting artistic strategy chosen by the artist that is quite unique in the exhibition. It focuses on the co-creation of the viewer, at least in their imagination, offering a space in which the viewers can create their own collective memory.

Daniel Adofo, Shackles of a Freeman: In this painting, the depicted (historical) slave and the depicting (contemporary) artist merge – an exciting example of the highly complex ways in which the relationship of the individual to the collective memory can be shaped. This does not happen in the painting itself, but in the tension between the artwork and the commentary. In this way, the artist transforms the historical experience of slavery and shapes it into a narrative denoting something else, something new. He uses the easily recognisable collective memory to create a self-portrait, collapsing both the public and private spheres into one image.

Nyameba Prince Anim, Yaa Asantewaa: Interesting to note is the contrast between the photorealism in the previous example and the quite opposite, ornamental-abstract solution here. The pattern in Nyameba Prince Anim’s design does not tell a story as the title suggests (the story of Yaa Asantewaa), although it refers to it. Guns and swords are symbolic of the ideas of rebellion against oppression and of longed-for freedom. But these symbols are braided in and interwoven into a decorative pattern, just as concrete historical events are woven into the collective memories, into what we call ‘grand narratives’. These narratives are created / constructed, as mentioned in the introduction to this section. They detach themselves from the single occasion, seeking their roots in the memories of the collectives themselves.