Dear user,

This section of our website forms the heart of the EVC project. Here you find a collection of images of objects from different ‘visual cultures’. Our contributors selected and interpreted them in their respective contexts believing that these objects are particularly important for intercultural understanding across boundaries. Each time a user opens this page, the order in which the objects appear changes. In this way we hope to avoid a hierarchical understanding of the collected objects as their entries continue to be accessed in the long run. The constant changing face of the page also reflects the continuous expansion of the collection. As there are already over more than a hundred entries, users may want to form an overview, or to navigate through the growing collection according to their interests. For this purpose, we offer the following search options:

Filter: This enables you to search for objects according to time, place, keywords, etc. / Free title search: If you know the title of an object, you can find it in the free search field. / Lab: In the lab section, objects from the database are grouped under overarching themes. This is an ongoing project and about to be expanded extensively.

Enjoy exploring our database!

-

Ernst Wagner

Ernst WagnerBased on the Ghanaian interpretation, it quickly became clear that certain ideological or political positions are immediately connotated with the respective image selection. These in turn are linked to historical and social experiences, which Winkler (2021) recently elaborated on the basis of the history of Germany. In our case, the West German, left-liberal intellectual milieu is of particular interest, since all the German project partners involved in the discussion can probably be assigned to such a milieu. "In the 1970s, the view prevailed among liberal and left-wing intellectuals in former West German, which objectively was not a nation state, did well to see itself as a >post-national democracy<. In the 1980s, this led to the conviction among many that the time of the nation state had passed and that Europe only had a future as a post-national union. [...] The self-destruction of one's own nation-state [in Nazi Germany - author's note] led to the conclusion that the nation-state as such had outlived its usefulness, and the term ‘national’ was equated with nationalist. [...] In Germany the idea that the nations had to merge into a European republic found a broader public echo." (Winkler 2020 p.186)

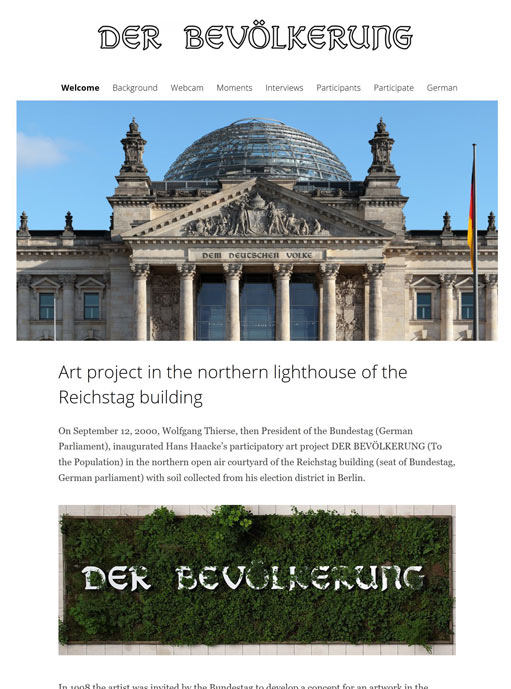

For art educators, the majority of whom probably feel committed to this idea of Germany as a post-national democracy, the question of a current symbolisation of national unity[1] is therefore obsolete. It cannot therefore be relevant to art education. A consensus in the German team on how at least the general topic could be addressed could be reached by the proposal to deal with the topic on another level, and to use Hans Haacke's installation "Der Bevölkerung" (2000, courtyard of the German parliament in Berlin) to deal with the topic of "national unity" in a contemporary art lesson.

Hans Haacke (*1936) is a German-American artist who has lived and worked in New York since 1965 and whose conceptually influenced works primarily address art-political processes.

Figure 2: View into the courtyard of the Reichstag building. © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

Haacke's installation "Der Bevölkerung" is located in a courtyard of the Reichstag building. This architectural context is part of the work. The building was constructed at the end of the 19th century, during the Second German Empire (1871-1918). In neo-baroque style, it paid homage to the national pomp under emperor Wilhelm II. Damaged by fire in 1933, it was further damaged during the Second World War. Located directly on the Wall to East Berlin, the dome was finally blown up in 1954. In reunified Germany, however, a new function was found for the building. Rebuilt according to plans by Norman Foster in the 1990s, it now serves the German parliament, the Bundestag.

Figure 3: View of the façade of the Reichstag building with the inscription "Dem Deutschen Volke" © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

Hans Haacke built a 21 x 7 metre rectangular, flat wooden enclosure in this building. He then asked the MPs to gradually fill it with soil from their respective home regions. In the middle of the box, the inscription "Der Bevölkerung" (To the People / Population) can be read, in white letters illuminated from the inside. The typeface corresponds to the inscription "Dem Deutschen Volke" (To the German People / Nation), which has been on the outside of the building's west portal since 1916.[2] According to the initiator, the invitation to bring soil from the constituencies is valid as long as members are democratically elected to the German parliament. A webcam, belonging to the installation (www.bundestag.de), takes a picture every day at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m. and thus allows a take a look at the development of the project since 2000 and at the current situation.

Figure 4: An MP distributes the home soil from his constituency in Haacke's installation. © Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

When Haacke proposed to install this large-scale installation in the new parliament in 1999, ten years after German reunification, it triggered a heated public discussion. Many MPs found the words "Der Bevölkerung" (To the People / Population), which appeared to be a dedication, inappropriate and provocative. Haacke was deliberately alluding to the older inscription "Dem deutschen Volke" (To the German People / Nation) on the outer façade. In contrast to this, he used the term " Bevölkerung - population" to refer to all the inhabitants of Germany, including people who do not have German citizenship and live here. According to his own statement, Haacke was inspired by Bertolt Brecht when deciding on the lettering. Brecht had written in 1935 in exile that whoever said population instead of people would avoid many lies (Brecht 1935). Haacke is obviously also concerned with the question of how words can and should be used in the context of a national parliament to designate the basis of this democratically elected representation of the people/population. Does the term "Volk" fit, a traditional, conventional but loaded and perhaps not at all accurate term? Or would be the term "population" better, a word that sounds unfamiliar and strange at first, but perhaps makes more sense. The discussion intended on such questions is part of Haacke's work.

Similar discussions were triggered by the idea of having MPs bring home soil. For many, this was reminiscent of the National Socialist blood-and-soil ideology. Or they criticised it as "kitsch" because of the well-intentioned but overused symbolism. Obviously, the work here plays with this iconographic tradition (“Heimaterde”), but reinterprets it just as it reinterprets the lettering. At the same time, the installation is constantly changing as a result - both through the ever-changing soil and through the growth of the plants over the course of the year.

Figure 5: Screenshot of the project's website https://derbevoelkerung.de

© Hans Haacke / VG Bild-Kunst.

The installation is thus in constant dialogue with the population designated in the inscription, tries to involve the MPs and responds as a living piece of nature to the stone surroundings of the parliament building. The work of art is thus never fully completed.

Haacke's art project was particularly controversial in parliament; only by a narrow majority did the MPs finally vote in favour of the realisation of the artwork in 2000 after a specially scheduled debate in the Bundestag. The entire debate is documented on the project's website - as another part of the work (Bundestagsdeabtte 2021).

[1] I.e. a "small German" solution after 1990 and with shifted borders after 1945.

[2] It was designed by the Art Nouveau artist Peter Behrens.

References

- Brecht 1935: Bertolt Brecht. Five Difficulties in Writing the Truth. www.literaturwelt.com/werke/brecht/wahrheit.html (13.10.2021)

- Bundestagsdeabtte 2021: https://derbevoelkerung.de/bundestagsdebatte/

- Kaernbach 2011: Andreas Kaernbach. Projekt „DER BEVÖLKERUNG“ im Reichstagsgebäude. https://www.bundestag.de/besuche/kunst/kuenstler/haacke/haacke-198996 (13.10.2021)

- Winkler 2020: Heinrich August Winkler. Wie wir werden, was wir sind - Eine kurze Geschichte der Deutschen. Munich (Beck)

- Winkler 2021: Heinrich August Winkler. Das widerspruchsvolle Erbe des Otto von Bismarck. In: FAZ of 18.1.2021, p.6

-

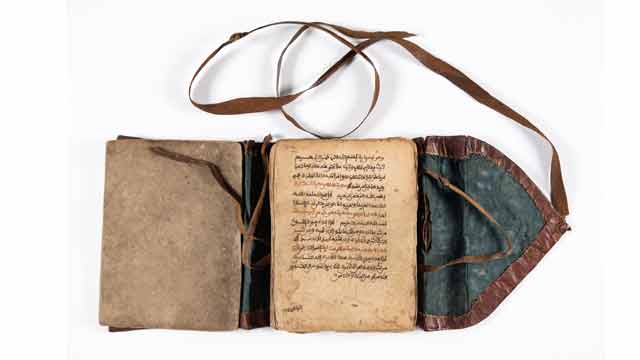

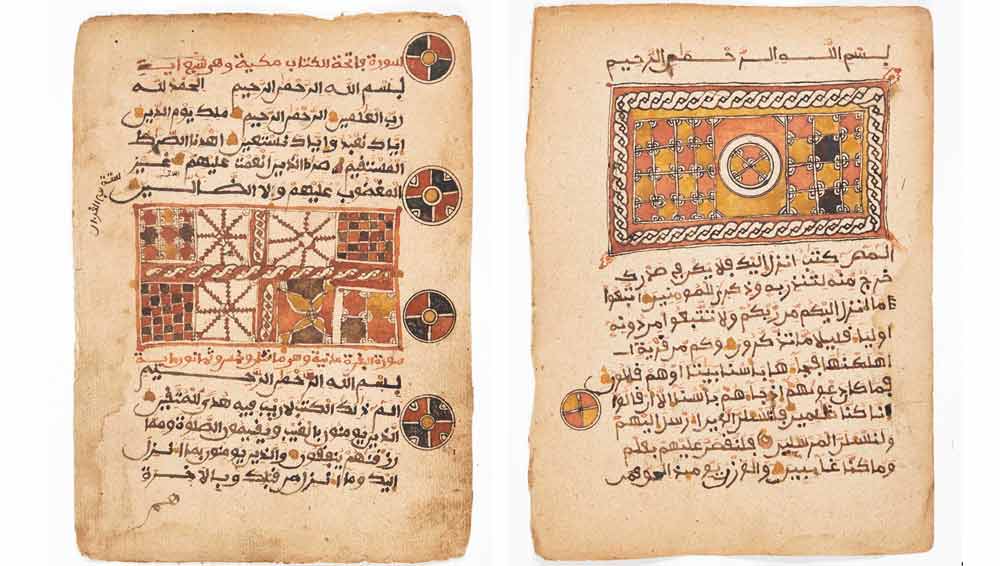

Mahmoud Malik Saako

Mahmoud Malik SaakoThe Qur'an is typical for the time and the West African region in general. The idea originated in North Africa such as Morocco and Algeria. But the writing was later, influenced by the Hausa and Mande scholars in West Africa. The texts in this Qur'an are the same as the original from Arabia. But there are differences in the kind of calligraphy found in these Qur'ans and those found in Arabia. One important aspect of these Qur'ans is the calligraphy that comes after the beginning of a new chapter or Surah. Again, the use of red, gold and black colour in writing the Qur'an makes them unique.

Artistic features of the Qur'an

- The leather cover used to protect the Qur'an was designed with some relief using black ink. It shows that leather workers were very important in society. Similar covers are made but in a form of a bag for the Qur'an while others are wooden covers with a leather thong used to hold the wooden covers together with the Quran.

- The Holy Qur’an has Ayahs (words or verses) and Surahs (chapters). There is Bismillah before each Surah. The Qur'an has 114 Surahs or chapters.

- Calligraphy works in some portions of the Qur'an. Calligraphy as the art of beautiful, decorative writing has existed in Islam since the word of God, the Qur'an, began to be written. In West Africa which was known to the Muslim world as Bilad-al-Sudan (land of the blacks), Islamic calligraphy naturally came with Islam. They are just symbolic to honour the holy text.

- The use of three colours in writing such as gold, red and black: This shows how versatile the person was in giving an artistic impression of the Qur'an based on the Kanemi

- A large decorated sign known as shurafah (ennoblement) is written at the end of every fifteen hizb (that is the division of the Qur’an into parts and portions). This is done as a means of honouring the holy text. (See images below.)

The shurafah or ennoblement at the beginning or end of a chapter (surah) is indicated in the two images. The gold, red and black colours are used to give it a splendid look. (Qur’an. 16th-17th century. Mossi in Togo. Museum Fünf Kontinente Munich. Courtesy Museum Fünf Kontinente. Nr. 20-3-1. https://onlinedatenbank-museum-fuenf-kontinente.de/detail/collection/b77d064f-c603-493c-af03-fc167f739586. [Stand: 08.08.24]. Photo: Nicolai Kaestner)

Material used for the Qur'an

The paper used is brown and a bit hard as compared to today’s paper used for printing. The ink is mixed in a variety of colours. There is jet-black ink that shines. Then there is a colour of black mixed with red and another colour which is neither black nor red. The ink is obtained through the following method. The roots of the desert date tree are collected and burnt into charcoal. This charcoal is then scraped into fine powder. The powder is filtered through a light piece of cloth. Water and gum Arabic are then added and the whole mixture is left to warm up in the sun. The mixture once prepared in this way gives out a very nice smell and its taste is very sweet.

Another method employed to produce the calligrapher's ink is to obtain the chaff of bulrush-millet (Pennisetum Spicotum), chips of the gum-yielding acacia (sieberiono), pods of the plant Egyptian mimosa (Acacia Arobico), slag from smithy and some bits of iron. All these items are then mixed with water. The mixture is filtered and boiled and once it is cooled it becomes ink. If the calligrapher wants a reddish colour or magenta colour imported dye of green or magenta colour is added. This type of ink is meant for the writing of the alphabet only and is always done in pure black. The ink is usually stored in small clay ink pots or small round gourds. The recent time, the ink is kept in small bottles.

What are the general specifics of these early Qur’ans?

The Qur'an is the holy text of the Islamic religion. In Islam, the Qur'an is believed to be the book of God’s words. The holy text remains sacred and unchanged since the beginning of time. The Qur'an is known as the most powerful text in Islam. Islam is a monotheistic faith and people of the religion take great pride in believing in pure monotheism. As followers of the Qur'an, Muslims must believe there is no one else besides Allah because Allah is the only one we worship sincerely, thus he is seen as the most powerful figure in the religion of Islam.

The Arabic text of the holy Qur'an in a book is known as the mus-haf (literally "the pages"). There are special rules that Muslims follow when handling, touching, or reading from the mus-haf. The Quran itself states that only those who are clean and pure should touch the sacred text. It is indeed a Holy Quran, a book well-guarded, which none shall touch but those who are clean... (56:77-79). The Arabic word translated here as "clean" is mutahiroon, a word that is also sometimes translated as "purified."

It was only Muslim believers who are physically cleaned through formal ablutions should touch or handle the pages of the Quran. Again, the Qur'an should be closed and stored in a clean or respectable place. Nothing should be placed on top of it, nor should it ever be placed on the floor or in a bathroom. Furthermore, when copying the Qur'an by hand, it should be legible with good handwriting. If you are reciting it you need to use a clear and beautiful voice. A worn-out copy of the Quran, with broken binding or missing pages, should not be disposed of as ordinary household trash.

Acceptable ways of disposing of a damaged copy of the Quran include wrapping it in cloth and burying it in a deep hole, placing it in flowing water so the ink dissolves, or, as a last resort, burning it so that it is completely consumed. But the translated Qur'an according to some scholars can be handled either by Muslims or non-Muslims.

Uses of the Qur'an

The Qur'an is meant for reading or recitation known in Arabic as taliwa. The recitation of the Qur'an is a highly honoured performance in Islam in which Allah blesses both the reciter and the listener. A person who memorizes the whole Qur'an is given the honorary title of a Hafiz (memorizer of the Qur'an). Again, the reproduction of the written Qur'an is as important as oral recitation. Two early calligraphic styles evolved in the writing of the Qur'an, Kufic (the more boxy, angular, heavy, and formal script) and Naskhi (the more elongated, rounded, cursive script).

The words in the Qur'an are regarded as the words of Allah and, therefore, handled with respect. Muslims also hold the view that some of the words contain mystical properties and as a result, Muslim religious scholars are sometimes consulted by people who have spiritual or psychological problems. They write verses from the Qur'an to ward off such evil spirits or for protection. The Qur'anic verses are often accompanied by diagrams drawn on a board and then washed off and given to the client to drink. As a result, these boards have high values based on the extent they have been used. It is believed that the older the board the more efficient it would be and vice versa.

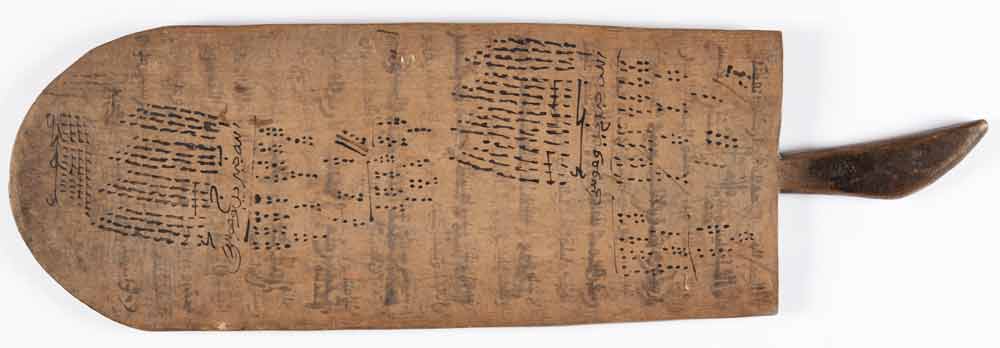

At the Museum, there is one of the Qur'anic writing wooden boards that have verses from the Quaran on one side and diagrams on the other side. This board is brown and round at the base with a handle in a form of an animal beak. The surface is smooth while some old writing has remained and can be seen (see image below).

Board (Courtesy Museum Fünf Kontinente. Nr. 9-48. Photo: Nicolai Kaestner)

Where is the Qur’an kept?

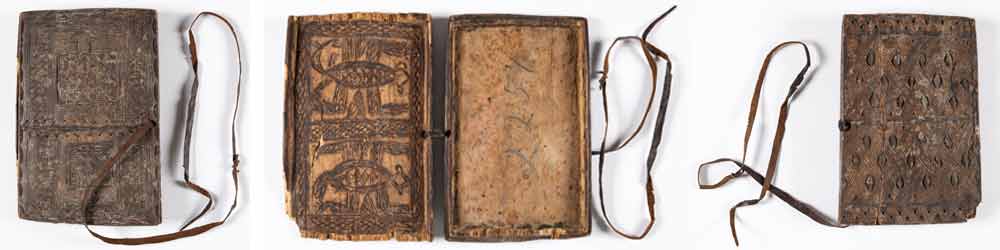

Old Qur'ans were usually placed in two wooden covers before the use of leather cases or bags. It was easy to carry it once it was placed either in the wooden covers or in the leather bag. This is very important not to mess up the loose papers of the Qur'an. The two wooden covers after the Qur'an is placed and bound with a thong. There are two holes in the middle edge of the covers where the thong is passed through to bind the two wooden covers with the Qur'an. This method of bounding the Qur'an with wooden covers was practised during the early Abbasid period. Many of the early Abbasid manuscripts were copied into several volumes based on the Kufic script which was fairly heavy and not very dense. The Qur'ans of this early period were bound in wooden covers, structured like a box enclosed on all sides with a movable upper cover that was fastened to the rest of the structure with thongs. In this period, the Quran was arranged into 20 Juz or parts instead of the original 30 Juz during the Umayyad period. These wooden covers can be found at the Museum Fünf Kontinente (Inventar Nr 15-17-148).

Wooden cover of a Qur'an. Museum Fünf Kontinente. (Courtesy Museum Fünf Kontinente. Nr. 15-17-148. Photo: Nicolai Kaestner)

Appendix

When is it read and how?

It is read during the five daily worship by Muslims, at leisure times, during periods of hardship, during important occasions etc. However, in West Africa, it is read even at funeral celebrations. In many instances, the whole Qur'an is shared among those who can read, or the 30 Juz are shared among 30 people who recite or read it.

Islam in West Africa

Islam as a religion was revealed to the Prophet Mohammed in the 6th century in the Arabian Peninsula. Africa was the first continent into which Islam spread, from the Arabian Peninsula in the early 7th century. By the 10th century, the Berbers of West Africa were converted to Islam by their North African counterparts. It was the Berber Muslims who began to spread Islam into Western Sudan by the end of the 10th century through their trading activities. The Berbers of West Africa also converted some of the Manding-speaking traders to Islam, and they also began spreading it alongside their commercial activities. It was the Mande traders who began to spread Islam into many parts of West Africa through trading activities. The nature of Islam made it easy for the indigenous people to accept it as adherents were able to tolerate, to some extent, some of the local beliefs.

Later, the Hausa from northern Nigeria were also involved in the Kola-nut trade in the mid-15th century. The rulers of many of the Western Sudanese States encouraged the trans-Saharan trade and extended hospitality to both traders and visiting Muslim clerics. The most crucial factor in the diffusion of Islam into many parts of West Africa was the conversion of some of the rulers to Islam. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, many rulers of the Mali and Songhai empires were Muslims and performed the annual Islamic pilgrimages to Mecca to establish trade relationships with the Muslim world. It was during the era of European colonization of West Africa that led to the spread of Christianity among the locals.

-

Leonie Chima Emeka

Leonie Chima EmekaIn 1682 a prominent French portraitist named Pierre Mignard (1612-1695) painted a large canvas of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth (1649-1734), one of many mistresses to King Charles II of England. The artist depicts her in a richly adorned dress, sitting on an upholstered bench against the background of a stone balcony that opens to a stormy sea. With one hand Louise de Kéroualle gently embraces her page, an African child. The fashion to hold black slaves, especially children, climaxed in the late fifteenth century, but also throughout the seventeenth century slaves were present in wealthy European households as servants.

Mignard’s painting lines up with other paintings of prominent provenance featuring African pages as an attribute of wealth: Titian’s Portrait of Laura Dei Dianti from ca. 1523 and Cristovao de Morais’ Portrait of Juana of Austria from 1535-1537 both depict an Italian respectively Portugal-based noblesse in company of an equally well dressed young African page. Like the duchess Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth the young female page, whose name is not conveyed, is dressed in beautiful European clothes. More peculiar however is the child's expensive pearl necklace. In the late seventeenth century pearl necklaces were a fashionable accessory for European women of extensive wealth. Imported from the Caribbean, Pacific and Indian Oceans initially by Iberian traders — later also by British and other European traders — the white, oval shaped pearls were an important trading good and symbol of prosperity and wealth. As such the valuable jewellery seems rather out of place on the neck of the page. It seems much more appropriate on the neck of the Duchess.

Fig. 1, detail

Compared to her page, the Duchess’s jewellery appears almost humble, as she wears the same pearls on small earrings. In a much higher amount, the same pearls are mirrored in a shell that the laughing child offers to her serious looking owner. In the other hand the page holds a red coral; a material that has become exceedingly valuable in many regions of West Africa. The most famous example is the kingdom of Benin (today in the region of Nigeria), where the red coral rose to a symbol of royalty and was appointed for the exclusive use of the Oba (Benin sovereign) and his household. The red coral in the hand of the African child connects the picture to the intercontinental trading network between Europe and Africa.

European merchants traded red corals from Mediterranean regions with West African traders or sovereigns in exchange for goods such as gold, ivory or slaves. In all her appearance, from her beautiful dress to her valuable attributes the representation of the African page refers to the trading network, which preceded her presence in the picture next to the Duchess. The servant acts as an attribute of wealth — well-dressed she represents the wealth of the person and house to whom she is made to belong to.

On the other side of the equator, there can be found relief works to a similar effect that allows us to further investigate the historical intercontinental trading network. Many brass reliefs, produced by the royal brass workshop in the kingdom of Benin in the 16th and 17th century, acted as attributes of economic and political power of the royal court. They represented the influence of the sovereign and the wealth of the palace where they were exhibited. A large corpus of brass plagues adorned the palace, which was the economic, religious, political and administrative centre of the kingdom of Benin. One example, currently in the collection of the anthropological Museum in Berlin, depicts two dignitaries flanked by two Omadas (palace servants) before the background of the royal palace. All of them wear pearl ruffs and headgear made of corals. Similar to Mignard’s painting, the corals also function as indicators of the far reaching diplomatic relationship of the Benin palace and symbols of the interregional economic influence of the royal household. The main trading partners to the kingdom of Benin had been Portugal and later Great Britain to whom they sold slaves, gold and ivory in exchange for brass, corals and weapons. However dissimilar the artistic technique of oil painting and brass relief might seem, in the coral they share iconographic meaning. The commodity of red corals make reference to the trading network between Europe and West Africa.

Fig. 2, detail

The trading relationships between Great Britain and Benin which were highly profitable for the rich and powerful in both kingdoms would change successively to an exploitative relationship; the final step to colonial subjugation was the British punishing expedition in 1897, which ended in the destruction of Benin and the robbery of the brass relief plaques to London, from where they were sold to institutions and private collections in Europe, the two Americas and Australia. Until today the royalty of Benin as well as the state Nigeria ask for restitution of the brass relief plaques and other works which were taken by the colonial power of Great Britain.

Peculiar about the Benin brass relief are the Portuguese heads that are engraved on the four palace columns in the background of the effigy. The Portuguese have a distinctive appearance with long straight hair and astonishingly long, pointed noses. In other reliefs the Portuguese are often depicted with Manillas, a ring in the shape of a horseshoe. The foreign metal of brass was imported to Benin by Portuguese traders. The valuable material, an alloy of copper and tin, supplemented cowrie shells as currency in the kingdom. As such the reliefs which adorned the royal palace were made of a material that circulated as money. The Portuguese merchants are depicted on a material which was an important means of their trade. Similar to the child holding the means of her enslavement in her hands, also the Portuguese heads are represented on and with the commodities which preceded their appearance in the imagery. Also British traders were depicted on brass reliefs, mostly with the attributes of armours, weapons and helmets.

At first glance the painting and the brass relief do not have much in common and a comparison seems rather pointless. One is an oil painting by one of the most famous portraitist of his time. The other was made by the prestigious royal brass workshop of the kingdom of Benin. When taking a closer look, however, one finds that both images — however different the outcome — both reveal similar means of constructing an image and its motive behind. The assets and people flanking the depicted patronages in the center of each image — on the one side the pearl necklace, red coral and the enslaved child, on the other the red corals, the manillas the Portuguese heads — build a network within the image that reflects on the economic trading network between both kingdoms. As both images were produced in the context of a royal court, and both intend to depict their far reaching trading relations, they may serve as documents to the complex histories and relations between the two kingdoms and if seen as such, may illuminate an important part of shard history that preceded the colonial era.

-

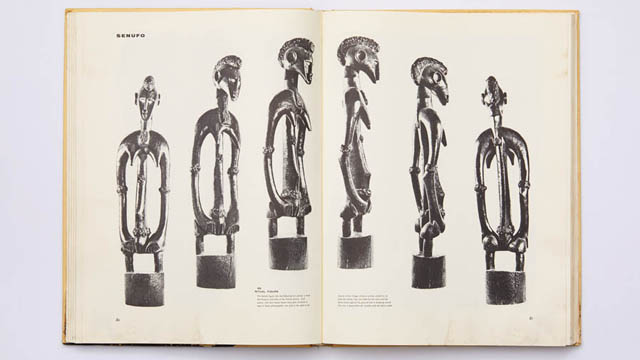

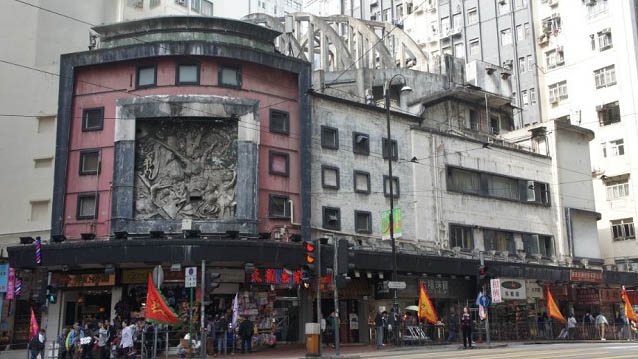

Stefan Eisenhofer

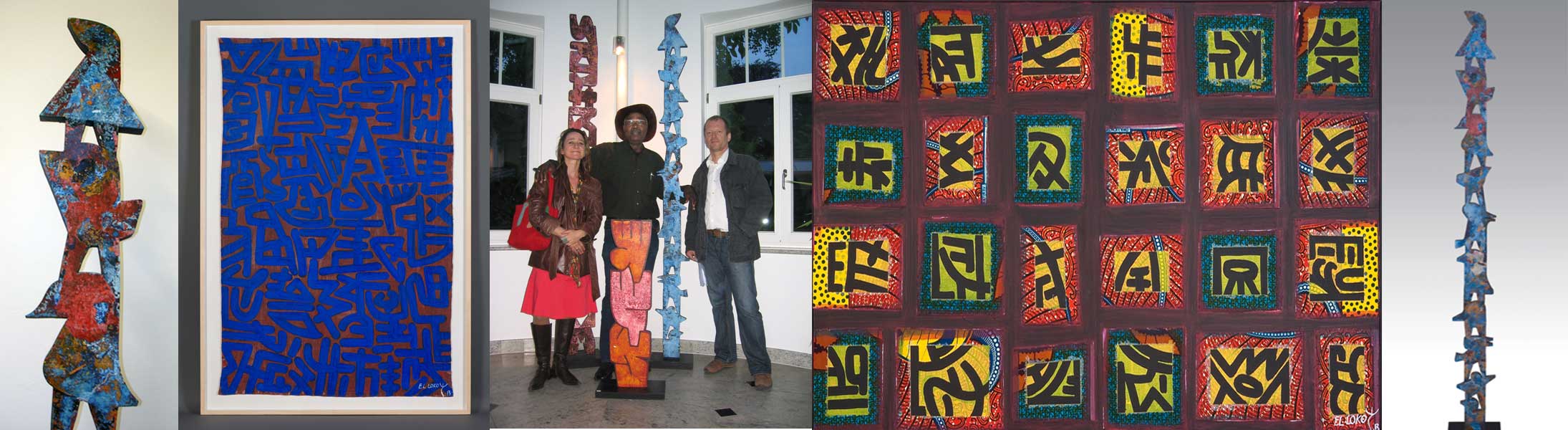

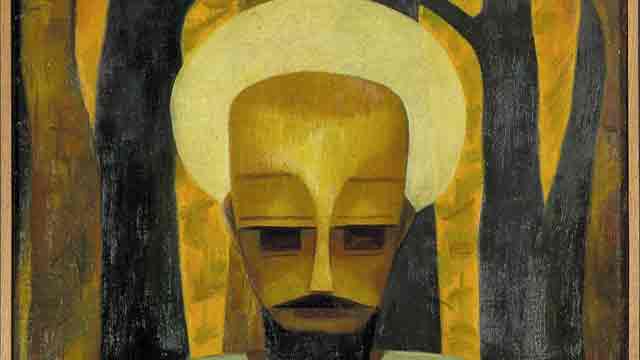

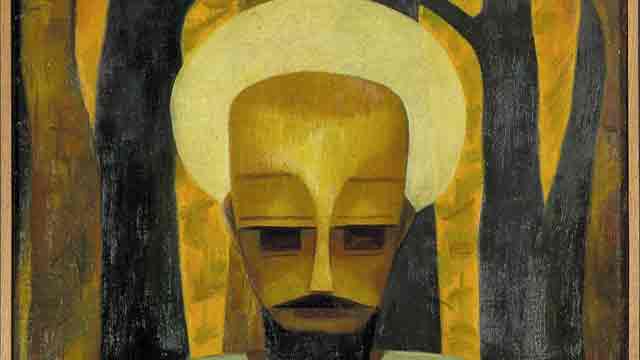

Stefan EisenhoferIn 1971, El Loko moved to Germany to study sculpture, painting and graphics with Joseph Beuys, Rolf Crummenauer and Erwin Heerich at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where he graduated as a master student in 1977. He created woodblock prints, sculptures, installations, drawings, graphics, photographs, paintings and performances in almost four decades, using an extremely wide range of working techniques and forms of expression. El Loko participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions on several continents and his work has been widely published. In addition, he repeatedly organised workshops for artistic and intercultural exchange in Europe and Africa.

El Loko, who lived and worked in Cologne (Germany) until his death in 2016, was one of the first African artists to venture into the art worlds of the West. His autobiographical book "Der Blues in mir" (The Blues in Me) - published in 1986, written in German and illustrated with woodcuts by the author - vividly recounts how he had to fight for and invent his identity and his path as a human being and artist at that time.

In Germany, El Loko experimented from 1972 onwards primarily with woodcuts before turning to painting in the mid-1980s. His series "Landschaften" (Landscapes), which interspersed colourful architectural elements with human faces, bodies and body parts and aesthetically dealt with the theme of threat, confusion and alienation in an urban context and how to overcome them, subsequently gained great popularity.

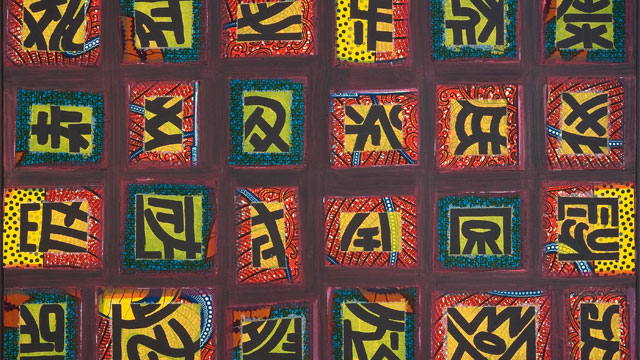

Subsequently, it became characteristic of El Loko that, for all the diversity of his work, he took up certain themes almost cyclically. His series of works "World Faces", "Cosmic Letters" and "Figure Landscapes" played a special role here, which he reinterprets again and again, seeking different perspectives and positions. Through a non-hierarchical treatment of the face or the bust portrait, the "World Faces" convey the vision's striving to abolish the differences between people of different origins, world views and gender. A utopian striving for a universal language and a global identity manifests itself in his series of works "Cosmic Letters", in a sense an alphabet of his own characteristic visual language. In paintings and pigmented steles made of wood and steel, El Loko combines ornaments, figurations, signs and ciphers of different origins and strives, by means of this symbolic sign language, for an art language that can be understood worldwide and for the construction of a meaningful world of his own.

Inspired by Joseph Beuys and the dissolution of the conventional bourgeois concept of art, El Loko also turned to temporary art actions from 1976 onwards. He developed his "duel performances", which combined poetry, song and drum rhythms and were characterised by the principle of rhetorical surprise and immediate reaction to each other.

In his installations, El Loko deals primarily with Western images of Africa and clichés in an often provocative manner. In his popular work "How to explain pictures to a pack" (1995), he ironically takes up Joseph Beuys' action "How to explain pictures to a dead hare" (1965): A gathered pack of 70 animals stands in front of a map of Africa hanging on the wall, composed of various elements and symbols like a puzzle. With this installation, El Loko not only posed questions about images of Africa, but also traced his own situation at the same time: The pack as the world that lies outside of him looks on the one hand expectantly, on the other hand more or less uncomprehendingly at him as an artist. In "The eternal mask" (2006), the artist painted 50 portrait photos of Africans with acrylic, alluding to Western views of African people: Through the disfiguring colour, the faces lose their individuality, become anonymous and frightening. In his work "Africa down", partly done in Cologne (Germany) and finished in Cape Town (South Africa), El Loko addresses the positions of Africans in the world. The visitors to the exhibition were forced to walk on 256 photos of Africans and 53 African national flags lying on the floor, through which the artist makes the oppression and devaluation of Africa and its people through colonialism and through corrupt, selfish and ignorant African rulers almost physically comprehensible. His provocative installation "Mohrenköpfe - Hohlköpfe" (2005), which questions the role of kleptomaniac politicians of black skin colour who systematically ruin their own continent and do not care about cultural matters or the economic or social development of their countries, aims in a similar direction. As in all his works, El Loko was not interested in simplistic answers or accusations, but in a serious examination of painful and uncomfortable topics as well.

Image 1: Vogelakrobatik, 1996, 250x30x20 cm // Image 2: PE.VO.TO.7, EL Loko, 2017, 135x99 cm // Image 3: El Loko at Museum Fünf Kontinente (Karin Guggeis, El Loko, Stefan Eisenhofer) // Image 4: Dokponou (Der Gescheiterte - The failed), El Loko, 2013, Acrylic on canvas, 80x120 cm. // Image 5: Vogelakrobatik, 1996, 250x30x20, Museum Fünf Koninente, Munich. All images: Copyright Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich.

-

Esther Kibuka-Sebitosi

Esther Kibuka-SebitosiThe Mandela House is located in Vilakazi Street 8115, Orlando West, Soweto. Now a museum, the Mandela House Museum is where the struggle icons Winnie Madikizela Mandela and her husband Nelson Mandela lived. There, they brought up their two daughters Zenani and Zindzi. Nelson Mandela spent little time at the house as he had to go underground during the struggle between 1946 until 1990s. He was arrested in 1962.

Winnie Mandela had to bring up the children while continuing the struggle. She was banished to the Free State town of Brandfort in 1977. Winnie Mandela was born in Mbongweni village, Bizana, Transkei on 26 September, 1936. She married Nelson Mandela in 1958. The marriage to a freedom fighter was a lonely one. The police often raided the Vilakazi Street 8115. Her husband was absent with meetings and amidst the turbulence she had to bring up the girls. In October 1958 she took part in the lady’s march to protest against pass laws. This was similar to the one in 1956 in Pretoria. She was an anti-apartheid activist and politician. She divorced Nelson Mandela in 1996 and was the minister of arts and culture from 1994 to 1996. She led a quiet life and on her 80th birthday, she was honored by family friends and politicians, including Julius Malema and the future President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa, and Patricia de Lille, former mayor of Cape Town. This demonstrated her relationships with all political parties. She passed on 2 April 2018. A true mother of the nation.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born in Umtata on 18 July 1918. At the famous Rivonia trial, Mandela was brought before the court for his involvement in sabotage and violence in 1962. He was imprisoned for 27 years in total. He was first sent to Robben Island but later transferred to Victor Verster Prison in 1988. He was released from prison after 27 years in 1990 and he came home for only 11 months, after which he moved to a bigger home in Houghton, Johannesburg. The former State President, de Klerk, ordered his release and removed a ban on the political movement the African National Congress. Mandela served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1991 to 1997. His Presidency is known for his legacy in ending racism, trying to fight poverty and inequality. He was dreaming of a nation free of racism with all people living together with all colours; the so-called Rainbow Nation. He wanted freedom without violence but the oppressors started killing his people. He then formed the Umkhonto we Sizwe, a military arm of the ANC. Nelson Mandela received a Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 with former state President of South Africa, Frederik Willem de Klerk.

The Mandela House has four bedrooms and one of them goes down memory lane. It brings both tears and relief, knowing that the Mandelas survived petrol bombs and bullets in the house during riots. The Mandela House Museum contains several honorary degrees awarded to Nelson and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. It also hosts artefacts, memorabilia and artworks including “Tears of Freedom” by Leonard Katete, a Ugandan living in Kenya. The museum is a monument of history, harbouring family photographs dating back as far as the 1950s.

The Nelson Mandela Museum is open for public tours and photographs are allowed.

Vilakazi Street was also home to Bishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu, who was an Anglican Bishop and theologian well known for his humorous and critical speeches that call to order the freedom fighters. He played a major role during the anti-apartheid and human rights struggle for South Africa. Bishop Desmond Tutu was honoured with a Nobel Peace Prize for his achievements in opposition to South Africa’s brutal apartheid regime. He took a non-violent yet fearless stance against the oppressors, a characteristic that made him stand out amongst the liberation leaders. He articulated the sufferings of ordinary South Africans in clear manner and at the same time spoke up about the oppressive regiment. It is not surprising that Bishop Tutu’s Peace Prize paved the way for strict sanctions against South Africa in the 1980s.

Bishop Tutu chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995. Due to the fact that South Africa had suffered many wounds during apartheid, the many crimes committed by white rulers and atrocities against the black majority, the commission was established to “enable South Africans to come to terms with their past on a morally accepted basis and to advance the cause of reconciliation." The lack of social cohesion mainly due to racial disharmony led the newly elected Government led by Nelson Mandela to put together the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) under the chairmanship of Bishop Desmond Tutu. Cases such as the Soweto Riots (1976), in which Hector Pieterson was killed, were discussed; the Sharpeville Protests (1960 and 1984) and a number of other prominent cases were dealt with. Forgiveness was recommended as the fundamental condition of healing.

Vilakazi is also known for the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, which were established to remember the Soweto uprising on June 16, 1976. Hector Pieterson was shot during the revolt on the day when schoolchildren demonstrated against the use of Afrikaans as a language of instruction for middle and secondary school.

Vilakazi Street and the Nelson Mandela Museum attract a number of tourists. The street is vibrant with good local food, music and dance. It has created small businesses in the township and is thereby contributing to the local economy.

References

- https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/winnie-madikizela-mandela

- https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/tutu-and-his-role-truth-reconciliation-commission, retrieved 26 January, 2019

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1993/mandela/biographical/ , retrieved 26 January, 2019

published April 2020

-

Constanze Kirchner

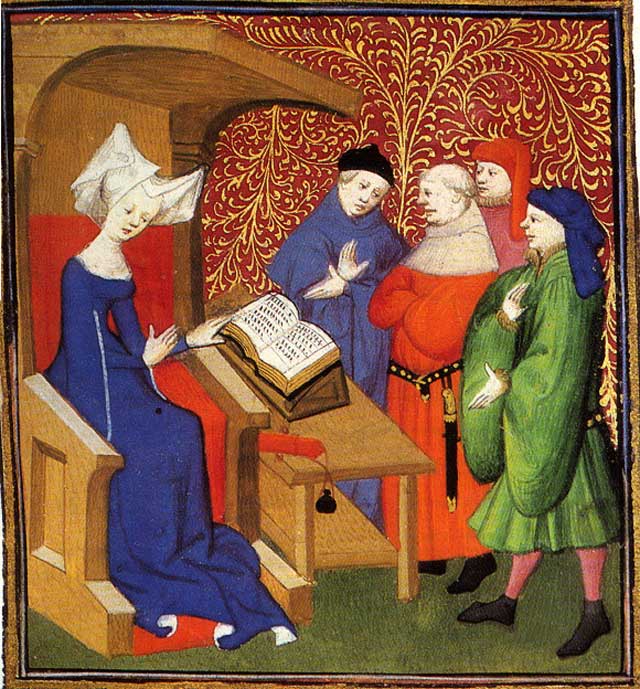

Constanze KirchnerThe motif Paradiesgärtlein originates from Christian imagery. It was painted many times in the 15th century, especially in Italy and along the Rhine. The enchanting devotional picture shows Our Lady enthroned on a bright red cushion in the middle of the garden, tall, in a radiant blue robe, as the figure dominating the picture. Her head is bowed and she is reading a book. A crown with leaves distinguishes her as the Queen of Heaven.

The Christ Child is playing at her feet. The other female figures in the left half of the picture are also to be understood as Holy Virgins because of their splendid clothing. A clear assignment of these saints is uncertain (Keazor 2001, p. 231 ff.). St. Barbara is probably drawing water with a golden spoon from the (life) well in the foreground on the left, because legend attributes to her miraculous powers in overcoming a period of drought. And it could be St. Dorothea who picks cherries from the (life) tree and puts them into the basket, although – according to the legend – the cherries are handed to her (ibid.). The figure holding the plucked instrument (psaltery) to the infant Jesus is interpreted as St Catherine of Alexandria or St Agnes. She is distinguished by a golden diadem with floral decoration and by her flowing hair (ibid.).

The group of figures on the right consists of the pensive Archangel Michael, also crowned with a golden plant, and – facing him – St. George in chain mail, next to whom lies a small dead dragon. A third figure, probably St. Oswald, bends down to both of them, as a raven peeps out from behind his knee (ibid., p. 233). He is holding on to the tree of knowledge. Saint George has of course already conquered the dragon, which stands for evil, and looks expectantly at Mary. Under another tree sits a frightened monkey with the distinct features of the devil.

According to biblical legend, he is held in check by the Archangel Michael, the fighter against evil and guardian of paradise. The apples mentioned in the creation story, which tempted to sin, lie ready on the hexagonal, bright white stone table. Wine and bread refer to the Last Supper. The table is compositionally remarkable, dividing the male group of figures from Mary.

Both paradise and the garden stand for a protected, enclosed and bounded place that provides food and water as well as peace and quiet. In the garden, flowers, herbs, fruits and grasses blossom and grow, spanning a supra-temporal, idealising arc from spring (lily of the valley) to midsummer (roses). Especially the white-flowered plants, such as the lilies, stand for the purity of Mary. Just like the plants, twelve birds of different species are depicted in detail and realistically - and thus identifiable (Brinkmann/ Kemperdick 2002, p. 93).

Compositionally, the colour scheme dominates the picture: the secular blue sky frames the graceful Mary leaning towards the book, whose blue robe corresponds with the blue clothing of St Barbara and that of the archangel. The white garments of the saintly figures, the wall in white tones and the light-coloured table enclose the baby Jesus, also dressed in white, in their midst. At the same time, the bright red of the virgins' robes, the red of Mary's book, her seat cushion, St. George's sleeves, the blossoms and fruits reinforce the clear composition, which is additionally underlined by the complementary green of the plants and once again places Mary at the centre of the picture's action. The spatial effect is essentially determined by groupings and overlaps of the figures and pictorial objects; there are no shadows in the heavenly world.

The figures appear relaxed, peaceful and serene, the colourfulness and the abundance of vegetation with springing water embody serenity and earthly happiness. The Holy Virgins are engaged in an occupation that does not cause any trouble. The clothing and hair ornaments are reminiscent of courtly life in a well-tended castle garden. This is also indicated by the killed animals, which are not usually part of the heavenly world, as well as a tree of knowledge that does not bear fruit. This combination of the divine world as a heavenly paradise with the impression of earthly reality characterises the picture to a great extent and thus lends it a peculiar mood, explosiveness and tension in its contemplativeness.

There are numerous studies on the painting technique, the use of colour, the symbolism, the identification, function and activities of the saints, the plants and animals. Also research has been done on provenance in the monastic context or on the attribution of the picture type as ‘hortus conclusus’ (closed garden as a symbol of Mary's virginity). ‘Hortus conclusus’ is often alluded to in paintings of Mary - a garden with an enclosure and with certain plants that refer to Mary (lily, rose, but also lily of the valley or strawberries) - as can also be seen in the Paradiesgärtlein. At the same time, however, the Paradiesgärtlein evokes associations with the gardens of pleasure and love, as found, for example, in engravings by the Master of the Gardens of Love in the mid-15th century (http://bildersammlung-prehn.de/de/node/946, 06.03.2019) - and in this ambivalence once again clearly emphasises the link between divine and earthly worlds of life.

What does the Paradiesgärtlein mean?

The Paradiesgärtlein defies a clear interpretation. The duality of good and bad is hinted at, but the victory of good in paradise over evil or sin – represented by the dead dragon and the vanquished devil – is clearly emphasised. However, the ideal state in paradise is not unbroken: With their tilted heads, the figures in the painting appear pensive, as if they know that there is a life of tormenting reality outside their shelter. The garden as a retreat from the dangerous outside world protects, where in everyday life there is oppression, fear of hunger or sudden death. With the devotional image, religion offers comfort in the promise of salvation to a paradisiacal existence in which the threatening is banished. The imponderable reality is countered by the protective enclosure of the massive wall – outside, the world is full of danger.

The devotional image builds a bridge from this world to the hereafter and vice versa. It opens up a view into eternity and thus into a transcendental space of experience that lies outside finite everyday experience. Visual means are used to create access to the divine, an access that at the same time recalls one's own experience of the world and yet enables the imaginative experience of transcendence.

As an anthropological constant, the idea of a transcendent reality, which usually characterises life after death, runs through many cultures. Experiences of transcendence are described in many ways and often refer to extrasensory perceptions and supernatural forces to which the respective belief is tied.

Why is the painting interesting for art education?

Transcendence and spirituality are often at the core of cultural traditions - in this case Christian heritage. It could be exciting to enter into a conversation about this and to draw on examples of non-European cultural testimonies of faith from the 15th century. In this way, world history can be opened up and a Eurocentric perspective on the history of Western art can be expanded. (As the epitome of European beliefs about the Garden of Eden, the work also stands at the end of the medieval conception of nature and art.)

The image announces divine truth: In paradise, the world is in order. Outside the garden, man lives in untamed nature and is exposed to all incalculable events. With its religious context of origin, the painting's function is primarily to depict an otherworldly, divine order that illustrates the promise of salvation after death in contrast to the earthly hardships of the late Middle Ages. But the pictorial interweaving of earthly and heavenly life already points beyond the late medieval conception of the image. The shielded divine world view experiences ruptures, opening and change.

Not only can the work paradigmatically explain the end of the Middle Ages and the development of art history. Furthermore, the it invites discovery: plants can be identified, animals and groups of figures with their actions tell stories that can be researched, re-enacted, developed further and transformed into the present day. And last but not least, the linking of divine and earthly reality allows analogies to virtual and real, individual and global worlds of life.

References

- Brinkmann, Bodo/ Kemperdick, Stephan (eds.): Das Paradiesgärtlein. In: German Paintings in the Städel: 1300 - 1500, Catalogues of the Paintings in the Städel Art Institute. Frankfurt am Main/ Mainz 2002, pp. 93 -120

- Leaflet of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut on the work: "Das Paradiesgärtlein", c. 1410-1420. Upper Rhenish Master, mixed media on oak, 26.2 x 33.4 cm. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main o.J., o.S.

- Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main, Prehn'sches Kabinett. http://bildersammlung-prehn.de/de/node/946 (06.03.2019)

- Keazor, Henry: "Manu et voce". Iconographic Notes on the Frankfurt Paradise Garden. Original publication in: Bergdolt, Klaus/ Bonsanti, Giorgio (eds.): Opere e giorni: studisu mille anni d'arte europea dedicati a Max Seidel, Venezia 2001, pp. 231-240. http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/2344/1/Keazor_Manu_et_voce_Ikonographische_Notizen_zum_Frankfurter_Paradiesgärtlein_2001.pdf (07.03.2019).

-

Jane Otieno

Jane Otieno

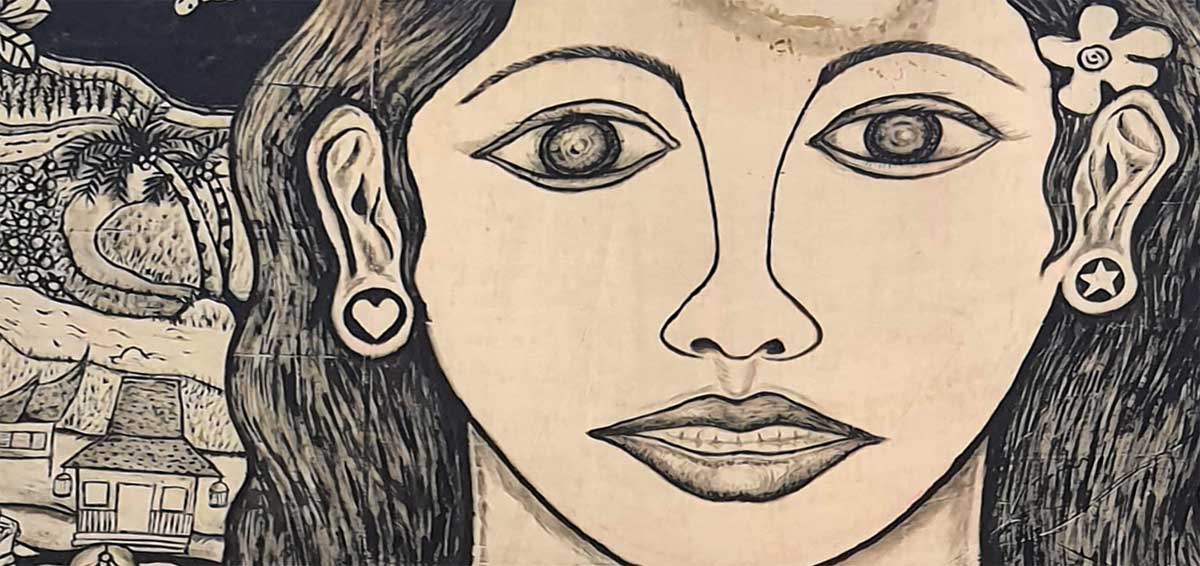

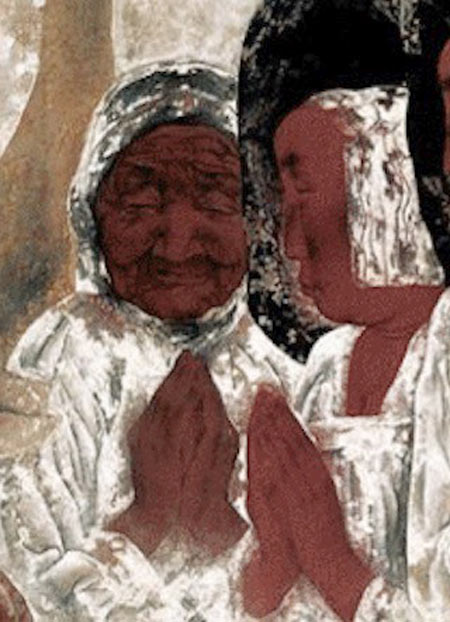

Detail (Photo: Avi Sooful)

The woman who seems to be in a reflective mood, shows a reserved demeanor and sadness. The face is not shaded, maybe to allow the viewer to project themselves more into the work and to give a clearer interpretation of the mood. The work done in ink probably with a filt-tip or a ball pen by use of line technique is effectively rendered in flowing, horizontal, curved and vertical manner to project her character and what she stands for.The good grasp of the leading lines sets the work in time and emotion. It creates a feeling of harmony between the individual and her surroundings and successfully portrays an element of resiliency in the midst of uncertainties. The subject’s predominance intimates to the viewer her feeling of absolute command of her surroundings with her well-coordinated and symmetrically placed figure. The woman communicates beyond the physical likeness and tells the viewer something about her character. There is no reason not to believe that she is protective of her space, bears compassion, at the same time, not afraid to share her feelings, pain, emotions and empathy that connects with others in openness.

Detail (Photo: Avi Sooful)

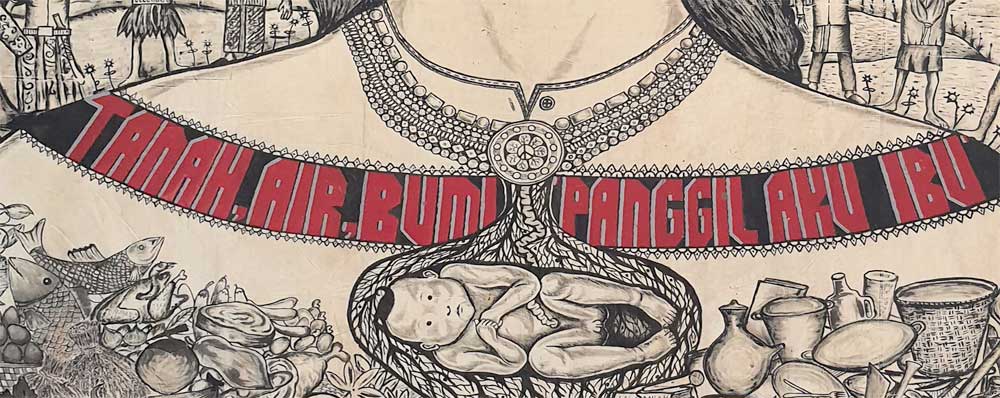

The writings written in red color, that reads ”Tanah, air, bumi, panggil, aku ibu” (Indonesian, to be translated as ”land, water, earth, call me mother”) around the neck is glaring and tends to hold the entire work in place. It is a strong message intended to communicate to the viewer on environmental awareness and conservation of natural resources. Perhaps a deliberate attempt by the artists to draw attention to the area, helping to convey thematic ideas that distinguish the woman from the rest of the picture. The necklace has a pendant with a distinct shape of a baby, probably in the womb, is a symbolic reflection of continuity and a cry for protection for all, including the unborn. They too matter! The fine textured background has other people, holding hands in solidarity, a sign of peaceful co-existence and social commentary on issues faced.

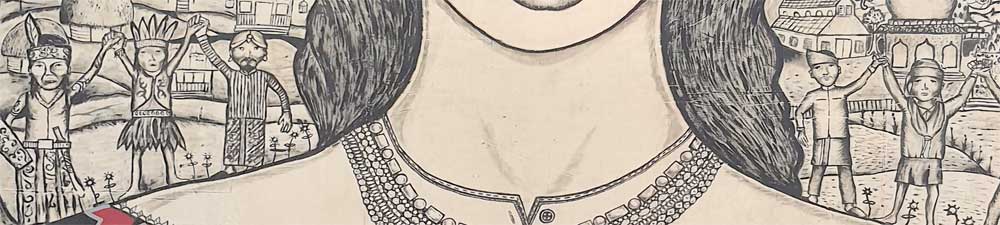

Detail (Photo: Avi Sooful)

The woman is against the destruction of what she holds dearly, and can foresee everyday activities such as fishing destroyed. The trees create balance in the work, while Rhythm and movement run across the canvas with reflection of real life situations, with a natural background that enhances the theme. The work’s portrayal of versatility and fluidity cannot be ignored. The relationships and interactions between the activities in the background and the main figure creates a complex meaning on nature’s importance for the human survival. The creatively rendered items held on both hands form part of the attire, thus creating a visual interest that has symbolic value. The firm, full, protective hands, held close to her heart, are symbolic of the strength of a woman, giving an impression of a mother, caregiver and a nurturer. The woman, in her use of direct gaze says “This is who I am” with her direct expression. She attempts to explain herself, to unravel her character, to invite the viewer to her space even if only for a moment.

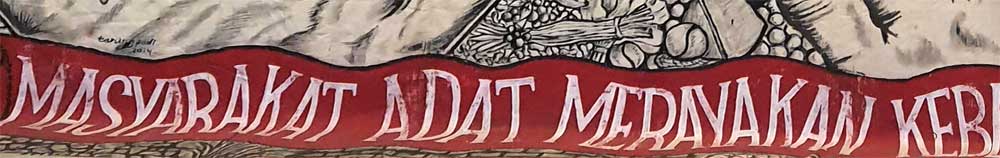

The drawing which is both engaging and intriguing, depicts the experience of understanding the environment and its connection to everyday life, “the goodness of mother earth”. It shows unity of purpose whereby different cultures from different continents come together in solidarity to support a common cause as the bottom inscription says: “Masyarakat adat merayakan keberagaman” translated “Indigenous people celebrate diversity”. The work substantially cultivates through an emotional approach the development of a connection of various cultures with nature for a common good. It underscores the importance of art as best suited to examine human existence, and that of earthly surrounding that reflects in everyday experiences and confronts the terror of the universe.

Detail (Photo: Avi Sooful)

Portrayal of how women play important roles in the construction of social and cultural meaning of different societies is evident. The realization of the goodness of Mother Earth is also shown to be a collective responsibility of all. The subject, executed from frontal view, is a woman in deep thought and a suggestion of underlying hidden pain and struggle for social justice that is explicit in various cultures. Her pain in addressing the social evils is captured more in her facial expression. Art as an expression of what it means to be human, is seen in the work that has religious expression, cultural undertones and creative energy. The artwork depicts a mysticism that is fabricated and intertwined in the socio-cultural realm, religious beliefs within different cultures. A view shared by Kumail (2017) who notes that art is a product of society’s members and so also reflects the culture and traditions of that society. Community members help to shape and evolve their culture through their efforts in the production of art. At the point when a society establishes its own particular character, the next generation is born, absorbs this identity, helps to spread it, and educates the world about it.

The black and white drawing portrays collective and creative abilities among different artists, with a show of a sense of togetherness that gives an idea of communal activity. The huge drawing distinctively points to the art of collaboration and understanding between different artists coming together for a common goal, which in turn, bonds them towards a shared future. The artists show their understanding of not only an aesthetic sensibility, but also an astute understanding of the local context, relationships and a co-creation process that engenders collective participation and ownership. The group work is a clear indication that artists do not function in isolation, and can use the visual language to transform a society. The work gives an impression of artists having good time as they work on one project thus creating a unique value of an artistic approach to community life and development. Lee, Lim, Liang, Zainuddin and Alhadad (2020) concur by stating that social issues are often unpacked when artworks are presented for sharing, eliciting further response, offering new opportunities for clarification, and imagination. The process thereby facilitates co-creation and joint decision-making because the finished product is not actually ‘finished’ as it continues to elicit reflection and dialogue. The arts are able to engage community in imaginative ways, creating a space for dialogue on community issues faced and also expanding the horizons of possible solutions.

CONCLUSION

Art is depicted in this work as a means of dealing with uncertainties and envisage of better future. The work expresses emotions that are not necessarily spoken but are powerfully rendered. The subject, overwhelmingly is suggestive of what the innate emotion is. The work brings in the significance of women’s voices and contributions as very critical in advancement of our societies. The artwork shows the diversity of artistic expression and how artists collectively use the visual language to transform a society. Different artists working together in one canvas, bring in different perspectives to properly convey the woman’s story that cuts across different cultures. The collaboration among the artists is a sure way of harnessing strengths and sharing resources through processes that foster mutual respect, shared decision-making and open communication. The artists show their understanding of not only an aesthetic sensibility, but also an astute understanding of the local context and a co-creation process, that gives rise to collective participation and ownership in development of society. Can interdisciplinary approaches to art appreciation widen perspectives of and sensibility to the meaning of art? Can collaborative creation of artworks across many media offer many avenues of self-expression and, is it an effective way in the teaching and learning of art in our institutions? How can art educators work collaboratively and explore the use of multicultural and cross-disciplinary teaching strategies in art education?

REFERENCES

- Kumail M. Almusaly (2017). Painting our conflicts: A thematic analysis study on the role of artists in peacemaking and conflict resolution. Nova Southeastern University. Department of Conflict Resolution Studies. College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Lee, Lim, Liang, Zainuddin and Alhadad (2020). The unique value of the arts in community development: A case study of ArtsWork Collaborative. Institute of Policy Studies, Lee Kuan. Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore & Singapore University of Social Science.

Photo credits

Belinga, R.C. Institute of Fine Art Foumban, University of Dischang, Cameroon & Sooful, A., University of Pretoria, South Africa.

-

Njeri Gachihi

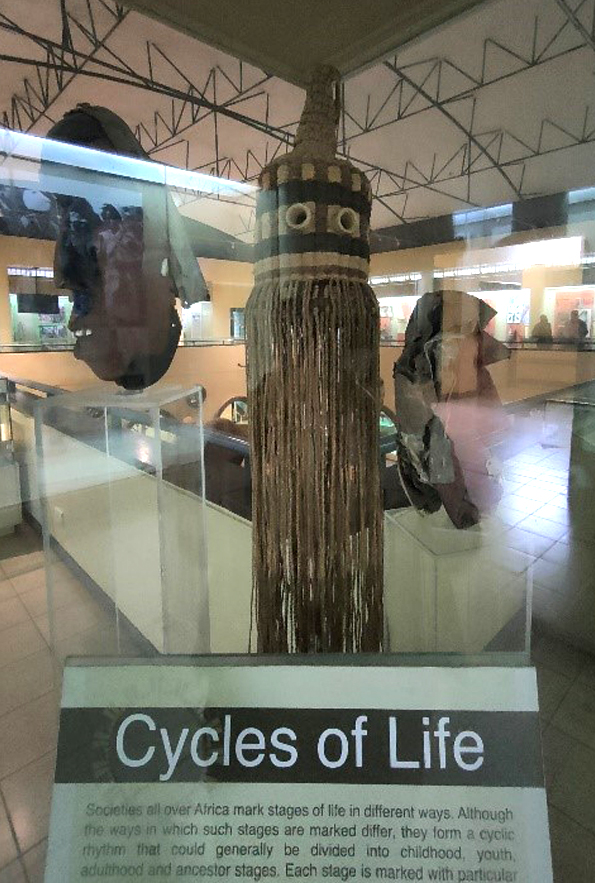

Njeri GachihiMeaning

Ingolole serves several purposes in the circumcision ritual. It serves to mystify the ritual and more so the initiate. While wearing almost identical masks, the initiates become undisguisable in this full seclusion regalia. It is believed that even evil spirit sent would have a problem identifying the target and hence revert to sender. On the other hand, the masks also serve to wade off and scare women and children who are not supposed to interact with them during the seclusion. Even when they go out of the forest and make processions on major roads singing and dancing, the women and children should stay away. Part of the chants, dance and singing done is meant to break loose ‘childhood/boyhood’ which is symbolized by the breaking of the crown - palm reeds attached on the ingolole. Some do manage to break it which is a sign of physical strength and masculinity as well as spiritual and ritual wellbeing.

The dance that the initiates perform is know as bukhulu/bakhulu which means elder. Bukhulu henceforth, cosmologically viewed, means unity with the ancestors and is also used to symbolize fertility or the life-giving seed (seminal fluid). The effort of breaking the reed henceforth translates into becoming an adult and gaining all the permission to undertake the adult roles and the responsibilities associated with it. This means that this right gives the initiate the ability and power to engage in full conjugal and social responsibility. Last but not least, the initiates spend a lot of time in the open. Ingolole then serves to protect them from the scorching rays of the sun, protect them from sweating too much when dancing and at night serves to protect them from biting cold, wild animals and insects.

Cutout: Presentation at Nairobi National Museum, Ingolole (Circumcision Mask), Museum Fünf Kontinente and Nairobi National Museum. Photo: Njeri Gachihi.

Cutout: Presentation at Nairobi National Museum, Ingolole (Circumcision Mask), Museum Fünf Kontinente and Nairobi National Museum. Photo: Njeri Gachihi.Is Ingolole an Artwork or a Ritual Object?

The ingolole as a form of ritual art, seems to bear witness to the resilience of the Tiriki culture; what Bakhtin might have called the 'carnivalization of the social order'. A central reason for using this mask, it seems, is to affirm the Africanization of the arena, both public and private, where a culturally appropriate image reigns. The mask usually invests the wearer with signs of power over evil, while modelling him on the norms of masculinity and respectability. The ingolole is one item of art that is yet to be transformed from artefact to curio (or momento). This is apparently so because its mechanism of distinction is yet to mobilize political as well as economic categories. This mask resonates well with the notion that visual art communicates cultural values. It is a complex ideological communication that derives its symbolism and references from culture. Yet it also draws its form and content from the fundamental tenets of the magical appropriation of power through the manipulation of depiction and elucidation.

Therefore, the Tiriki Circumcision mask, Ingolole is not only an artistic representation. It is a ritualistic object that embodies several meanings. It is known to invest the wearer with signs of power over evil - in that the wearer is set apart from his enemies that would intend to inflict harm. It is believed that the evil spirits sent to cause harm on the initiate would find it difficult to positively identify the initiate. At the same time, it causes mystery around the initiates making their looks terrifying and hence keeping off those who are not permitted to come near newly initiates. Physically, it protects the young boys from scorching sun, biting cold and insects while in seclusion. Once ingolole is used, it is kept and passed on from generation to generation. A used one is still valuable to the family and must be kept safely to avoid causing harm to the members of the family. Hence, this is an item of art that cannot be easily transformed from a ritualistic artefact to a simple curio craft.

There are not many Ingolole’s in our Museum in Nairobi. Two are however exhibited in the permanent exhibition, Cycles of life, at the Nairobi National Museum.

Presentation at Nairobi National Museum, Ingolole (Circumcision Mask), Museum Fünf Kontinente and Nairobi National Museum. Photo: Njeri Gachihi.

Presentation at Nairobi National Museum, Ingolole (Circumcision Mask), Museum Fünf Kontinente and Nairobi National Museum. Photo: Njeri Gachihi.

-

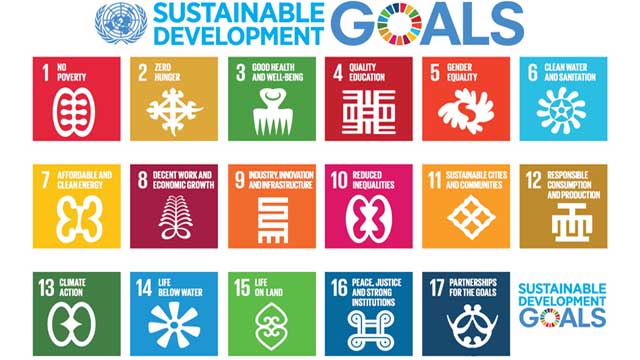

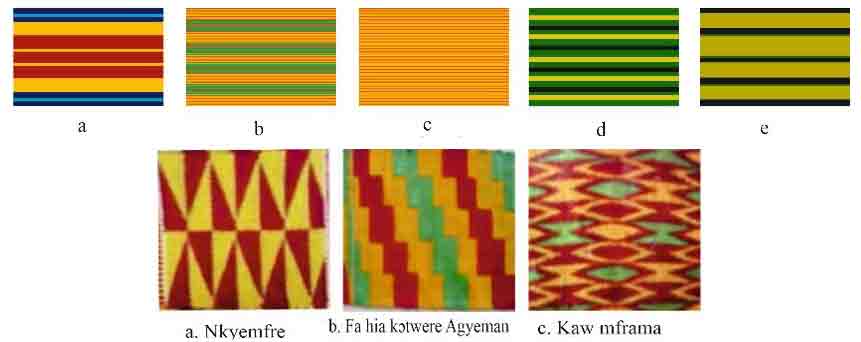

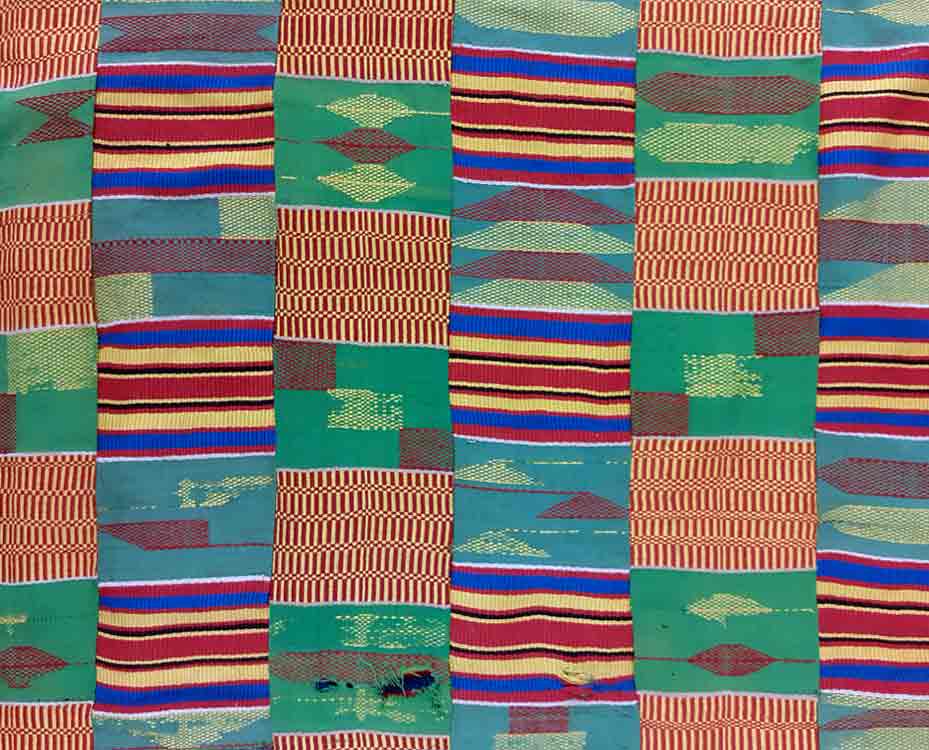

Patrique deGraft-Yankson

Patrique deGraft-YanksonWe may be right to assume that the level of awareness just at a little over four years of its implementation should not be too alarming. However, analyzing such low level of SDGs awareness among a people a country whose president is a Co-Chair of the Eminent Group of Sustainable Development Goals Advocates in Africa leaves some cause to worry.

The good news however is that, not being directly aware of the SDGs in the way they have been blueprinted does not mean the people are insensitive to its calls and claims. The fact is that, most of the demands of the SDGs are already embedded in the culture and belief systems of the people, and I consider this as an important resource to deploy for awareness creation and enthusiastic implementation of the SDGs.

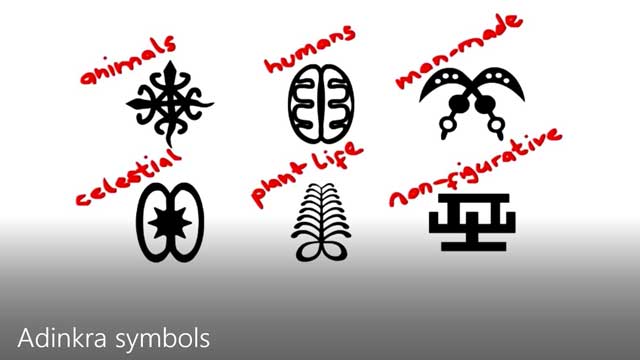

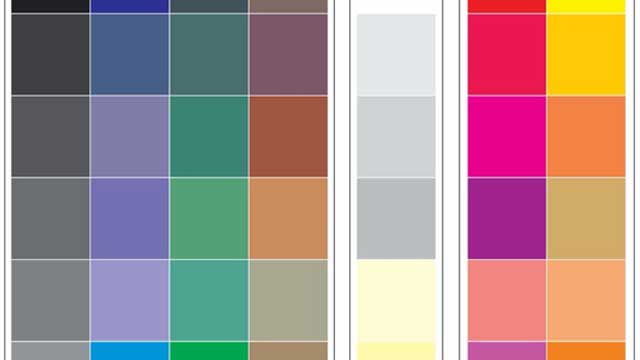

For the realization of UNs commitment to leave no one behind in the mobilization of the citizens of the world to achieve the 2030 agenda (UN, 2020) therefore, I am of the belief that efforts at linking the relevance of the 17 goals to cultural manifestations of the people should be highly considered. The image shown above is a demonstration of how various traditional symbols speaks to the SDGs in a language which is understood by the traditional Ghanaian. These symbols transcend language barriers and their meanings are inherent within their traditional belief systems, making the goals both physically and spiritually relevant to people.

The meanings of the symbols are as follows:

Ese Ne Tekrema (The teeth and the tongue)

Symbol of generosity towards one another. Through the formation of a linear relationship in diversity towards a common goal, both the personal and societal needs of the people will be realized.

Funtumfunafu Denkyemfunafu (Siamese/conjoined crocodiles)

Symbol of brotherly feeling, caring and sharing. The society stays stronger when people coexist in the belief that we all smile and grow together when we feed and enjoy the good things in life together.

Dua Afe (Wooden comb)

Symbol of sanitation, cleanliness and beauty. This symbol reechoes the essence of physical and spiritual wellbeing through personal and environmental cleanliness.

Nea Onnim No Sua a, Ohu (Anyone who does not know is capable of ‘knowing’ through education)

Symbol of educational opportunities. This symbol plays down ignorance by reminding people of their inert capabilities to get educated to any level of their preference. In other words, opportunities for quality education exist for all.

Obi Nka Bi (No one bites the other)

Symbol of equal regard, recognition and treatment for all. No one bites the other as a value ensures that all genders and age groupings have equal rights for existence in the society which allow them to listen and be listened.

Sesa Wo Suban (Change your life)

Symbol of deterrence and admonition towards all unapproved societal behaviors that affect the natural environment. This symbol represents strong advocacy for transformation and dynamic life patterns that affect nature. One of the unacceptable life patterns this symbol is currently addressing is the Ghanaian youth’s preference for wealth through illegal mining which destroys precious water bodies

Pempasie (Sew in readiness)

Symbol of production and sustainability. This symbol emphasizes the importance of societal preparedness and readiness for the future through effective production and management of all resources for posterity.

Aya (Fern)

Symbol of resourcefulness through resilience, self-reliance, hard work and judicious engagement of the environment and its resources.

Nkyimkyim (Twisting)

Symbol of collective action towards the building of the human society through initiative, dynamism, versatility, innovation and resilience. Indeed, building a successful society, like life itself, is not a smooth journey. The journey of life is tortuous and it requires a great amount of innovation and creativity to sail through.

Nkonsonkonson (Chain)

A symbol of unity. This symbol, depicting two links in a chain, advocates for the need to heal the componentized society since in unity lies strength.

Eban (Fence)

A symbol of love, safety and security. The fence symbolically secures and protects the family from unhealthy activities outside of it.

Hwehwe Mu Dua (Measuring stick)

Symbol of examination and Self/Quality Control. This symbol emphasizes the need for circumspection in all human endeavors. It directs attention to self and quality control in everything including production and consumption. It admonishes against over consumption, over production and all forms of egoistic instincts and behaviors which adversely affect the general good of the society.

Nyame Biribi Wo Soro (God resides in the heavens)

Symbol of reverence to the heavens, the abode of the Supreme Being. Recognition to the ‘heavens’, or the skies as the residence of the supreme being is tied to the belief that all good things come from the heavens – rains, sunshine, fresh air, etc. The ‘heavens’ need to be respected for continuous flow of life-given goodies.

Ananse Ntentan (Spider’s Web)

Symbol of knowledge and wisdom about the complexities of life. This symbol alludes to the intricate personality of Ananse, the spider, a well-known character in Ghanaian/African folktales. In Ananse’s world, all facets of life need to be somehow manipulated, positively or negatively, for good or bad reasons. This sometimes led him to dire situation. Ananse therefore is a character for admonitions and reprimanding. Being conscious about the character of Ananse guides your steps against any unfair treatment to the world around you, be it the skies, on the land, in the waters or below the waters.

Asase Ye Duru (The Earth/Land is heavy)

Symbol for reverence and recognition to the providence and the divinity of the ‘Earth/Land’ and everything associated with it. The ‘Earth’ is the mother to everything. It carries the entire humanity, trees, water bodies, the sea (and what is in it and beneath it), big and small animals, etc. This why it is described as ‘heavy’. Respect/reverence to the Land is respect/reverence to life.

Mpatapo (Knot of Pacification/Reconciliation)

Symbol of bonding and adjudicatory factor which brings back parties in a dispute to a peaceful, harmonious and reconciliatory coexistence to ensure unified and strong societies and institutions.

Ti Koro Nko Agyina (One Head does not forma Council)

Symbol for partnership, collaboration and teamwork. This symbol emphasizes the importance of cooperation and collective efforts in the realization of all goals. Obviously, the attainment of the SDGs is a collective responsibility. No one nation (one head) can make it happen. It takes the concerted efforts of the entire citizenship of the world.Bibliography

- Adinkra Brand, A. (2020, November 15). African adinkra symbols and meanings. Retrieved from Adinkra Brand: https://www.adinkrabrand.com/blog/african-adinkra-symbols-and-meanings/

- Kasahorow Adinkra Library, K. A. (2020, November 15). Adinkra symbols and meanings. Retrieved from Kasahorow Adinkra Library: https://www.adinkrasymbols.org/symbols/nkyinkyim/

- United Nations, U. (2020, December 7). Sustainable Development. Retrieved from Uited Nations: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda-retired/

published January 2021

-

Elfriede Dreyer

Elfriede DreyerThe Richtersveld National Park in South Africa has some of the most beautiful and hardy vegetation in the world. The 'botterboom' ('butter tree') (Tylecodon paniculatus) is but one example hereof. According to Wikipedia (RICHTERSVELD 2008), "The plant appears to have wide tolerance of growing habitats, growing in weathered rock in the north to coastal sands in the south. The plants can reach heights of 2 m making them the largest of the tylecodons. Tylecodon paniculatus is summer deciduous. The plants conserve energy by photosynthesizing through their 'greenish stems' during the hot dry summer months. The yellowish green, papery bark is a very attractive feature of this plant and has given rise to the common name. During the winter, plants are covered with long, obovate, succulent leaves clustered around the apex of the growing tip. [...] In nature the plants tend to grow in groups, making a spectacular show when they flower. [...] The shrub is reported to have a surprisingly weak and shallow root system for its size." This plant is representative of many other African succulents and bulbous plants that have shallow root systems and can therefore easily adjust to desert and other harsh environmental conditions. They change their leaves into thorns and the surface to protect the plant against the loss of water.

The metaphor of the succulent is of particular interest to an engagement with nomadic identity in the context of a continent such as Africa that has been subjected to "wicked, messy problems". Being similarly exposed to a severe environment, African people have accustomed themselves to survive in difficult circumstances and to a large extent have become nomadic as a result. In many cases they have adopted itinerant lifestyles and form groups for protection, safety and cultural coherence. Living on a vast continent, they are accustomed to long journeys; however, poverty, violence, civil wars, colonial and other imperial infiltrations and oppression have resulted in a focused nomadic condition where people are constantly moving and travelling in the search for a better life and even survival. Aligning contemporary culture with nomadism, Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (1996) appropriates the stereotype of the pilgrim who is on a teleological journey - ordered, determined and predictable - but cannot come to rest and leave a footprint in the sand. They operate through a 'shallow root system'.

Bulbous succulent plants are essentially botanical rhizomes, a concept that inspired the notion of the rhizome as a philosophical concept, initially developed by Gilles Deleuze (philosopher) and Felix Guattari (psychotherapist) in their Capitalism and schizophrenia (1972 -- 1980) project. Deleuze and Guattari (1987:7) state that the "rhizome itself assumes many diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion in bulbs and tubers". In "A thousand plateaus" (1987 [1980]) they introduce the concept of the rhizome as follows (assigned to cultural patterning):

1. Principle of connection: any point of a rhizome can be connected to any other

2. Principle of heterogeneity: any point of a rhizome can be connected to any other

3. Principle of multiplicity

4. Principle of a signifying rupture: a rhizome may be broken, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines

5. Principle of cartography and

6: Principle of decalcomania: a rhizome is not amenable to any structural or generative model; it is a map and not a tracing.

Deleuze and Guattari's model allows for a cultural view that entertains non-stable relationships, subjectivity, relationalism, multiplicity and volatile positions. Similarly, Italian contemporary philosopher and feminist theoretician Rosi Braidotti (2011:3) views the nomadic predicament and its multiple contradictions have come to age in the third millennium after years of debate on the "'nonunitary' - split, in process, knotted, rhizomatic, transitional, nomadic - so that fragmentation, complexity and multiplicity have become everyday terms in critical theory." Since the 1990s Braidotti has been engaged with the question as to what the political and ethical conditions of nomadic subjectivity are, grounded in a "politically invested cartography of the present condition of mobility in a globalized world" (Braidotti 2011:4).

South Africa has experienced turbulent histories over the last two centuries and nomadic movement was brought on by volatile colonial, postcolonial and global upheavals, leading to political and social displacement and consequently hybrid identities. Having been a British as well as a Dutch colony, South Africa has since 1652 shown cultural patterns of movement in and out of the country, and from place to place. During apartheid non-whites or 'people of colour' were viewed as not belonging and were removed from the city; forcibly established in townships outside the city; only allowed as workers into the city; and had to carry passbooks (identity documents) on them all the time. For many decades now, in postapartheid South Africa, migrants from all over the continent have been flocking to the country in search of a better life and even survival, and they mostly live in temporary shelters. Many other sociological and cultural problems have emanated as a result of the migrant issue, based on subjective racism, xenophobia, crime and fear for the other.

Identity (and subjectivity) in the African modernist context is neither stable nor fixed, and the corporeality of the artist-as body and the artwork-as-process in this specific part of the world henceforth has produced liminalities in many ways. Often rooted in a rural or small-town environment, African artists generally tend to move to multicultural, cosmopolitan cities where gallery and industry networks are in closer proximity. Those in the rural remote parts of Africa make it their business to connect through digital and social media in order to stay connected, current and noticed.

The art of South African artist Diane Victor provides an eminent example of nomadic identity depiction. The artist utilises various ephemeral media in her work, such as ash, crushed charcoal and staining. In Perpetrator 1, 2008, a so-called smoke portrait, she has used the deposits of carbon from candle smoke on white paper to draw with. The work is exceedingly fragile and can be easily damaged, disintegrating with physical contact as the carbon soot is dislodged from the paper, and in this way speaks about the fragility, precariousness and insubstantiality of a nomadic human condition. Although the smoke portraits started with a series on AIDS victims in 2003, Victor continued to depict various other individuals, commenting on ephemeral politics and ideas, and life generally as a temporal entity. In this work she depicts a perpetrator with reference to the previous South African apartheid dispensation and the atrocities of its perpetrators, but also to counter racism and the violence committed in the name of political redress. The Perpetrator's race is indeterminate, but his gender is certain, as well as the cruelty of his dispensation. Severed from the body, the Perpetrator's head becomes a rhizome that is not 'rooted' in a body, but uprooted, derooted, and floating with tubular arteries as corms hanging from it like a beheaded monster.

As an ephemeral, nomadic image, Perpetrator 1 speaks about a decolonial condition that presents the ambivalent Baumanian idea of the pilgrim-tourist who keeps going in circles, driven by an ideological sense of survival. Nomadic identity is essentially rhizomatic, and in Africa, as in many other parts of the world, the drive to belong and the utopian quest for a better life have resulted in identity being redefined, renegotiated, rerooted and sprouting in many directions.

References

- Bauman, Z. ‘From pilgrim to tourist – or a short history of identity’. In Hall, S and Du Gay, P (eds). 1996. Questions of cultural identity. London/New Delhi/Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Braidotti, R. 2011. Nomadic subjects: embodiment and sexual difference in contemporary feminist theory. Second edition. Gender and culture: A series of Columbia University Press. New York: University of Columbia Press.

- Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. 1976. Rhizome: Introduction. Paris: Éditions de Minuit. [based on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Capitalism and schizophrenia project (1972 - 1980)].

- Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. 1987 [1980, French original]. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Athlone Press.

- RICHTERSVELD NATIONAL PARK - VEGETATION: BOTTERBOOM (Tylecodon paniculatus). 2008.Available: https://www.richtersveldnationalpark.com/vegetation_botterboom.html (Accessed 3 January 2019).

published April 2020

-

Runette Kruger

Runette KrugerCape Town based Tokolos Stencil Collective uses stencil and graffiti to address socio-political issues such as lingering racial inequality, labour exploitation, segregation, and poverty. The name of the collective refers to a dwarflike mythical being, the tokoloshe, that materialises at night to frighten unsuspecting victims, now mobilised by the Collective to “terrorise the powers that be”, or, the status quo of inequality (Tokolos-Stencils, 2015). The declared aim of the Collective is to highlight continuing spatial and social segregation in a post-apartheid South Africa (Botha, 2014).

The social discrepancies whereby the majority of South Africans continue to experience social and economic isolation are addressed by Adato, Carter and May (2006), who cite the Poverty and Inequality report of 2000. In the report, South Africa is described in terms of two parallel worlds, “one, populated by black South Africans where the Human Development Index (HDI) was the equivalent to [that of] Zimbabwe or Swaziland. The other … [populated by] white South Africa in which the HDI [was] between that of Israel and Italy” (Adato, Carter and May, 2006, p. 226). This inequality had, disturbingly, only deepened between 2000 and 2006, and in a March 2018 report by the World Bank, South Africa is cited as the most unequal country globally in 2015, based on the Gini coefficient of 0.63 of that year (World Bank, 2018, p42). The Gini coefficient measures the gap in income between the wealthiest and poorest members of a population. A score of 0 would indicate absolute income equality, and a score of 1 would indicate that one person owned all the wealth. This disparity, as well as the resultant exploitability of the poor, informs the Tokolos Stencil Collective’s main subject matter.