Dear user,

This section of our website forms the heart of the EVC project. Here you find a collection of images of objects from different ‘visual cultures’. Our contributors selected and interpreted them in their respective contexts believing that these objects are particularly important for intercultural understanding across boundaries. Each time a user opens this page, the order in which the objects appear changes. In this way we hope to avoid a hierarchical understanding of the collected objects as their entries continue to be accessed in the long run. The constant changing face of the page also reflects the continuous expansion of the collection. As there are already over more than a hundred entries, users may want to form an overview, or to navigate through the growing collection according to their interests. For this purpose, we offer the following search options:

Filter: This enables you to search for objects according to time, place, keywords, etc. / Free title search: If you know the title of an object, you can find it in the free search field. / Lab: In the lab section, objects from the database are grouped under overarching themes. This is an ongoing project and about to be expanded extensively.

Enjoy exploring our database!

-

Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel

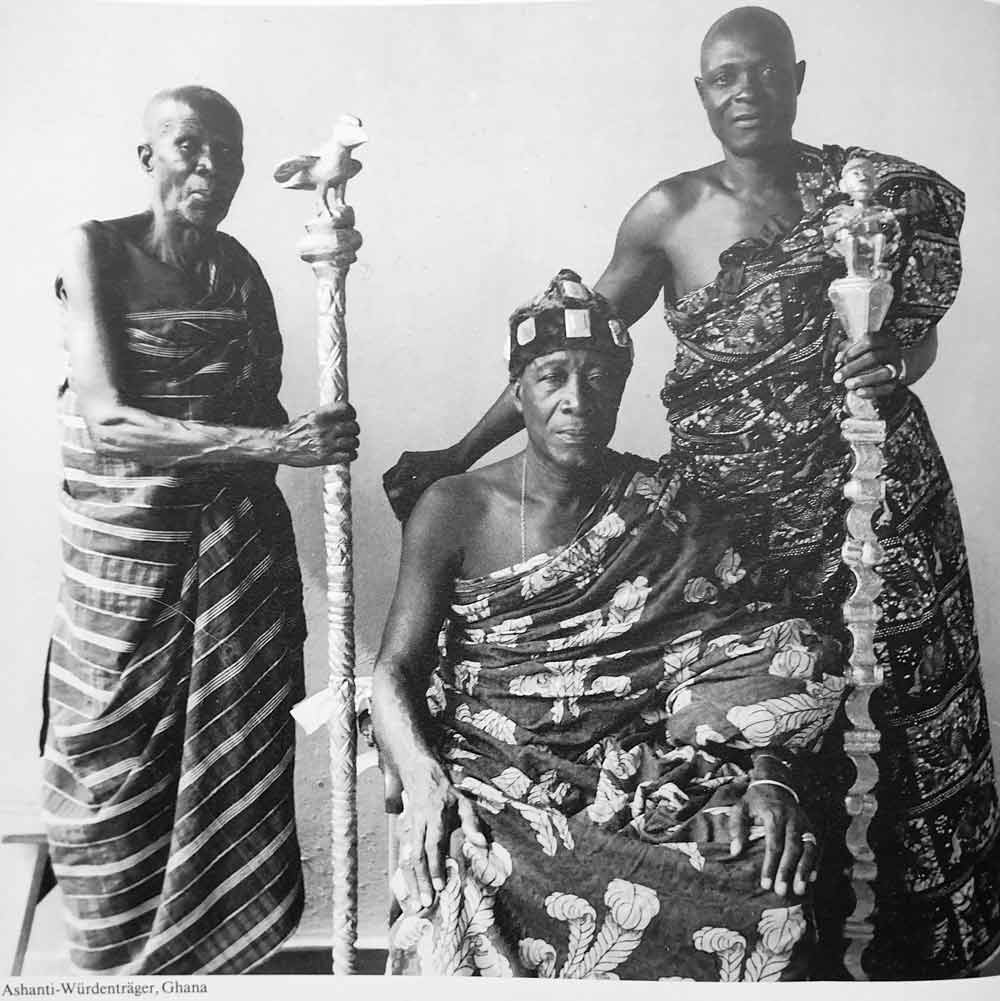

Osuanyi Quaicoo EsselFashion accessories help in decorating the human body and act as an essential influencer of accessories production and commodification. By decorating the human bodies, fashion accessories heighten the aesthetic aura around its wearers based on the precepts of the standard of beauty held by the society that created such objects. The production and commodification of fashion accessories are universal to different cultures across the globe. It happens in different parts of the world, including Africa. On the continent of Africa, different societies have demonstrated their creative prowess in fashioning accessories for the decoration of human bodies. For example, the Asantes of Ghana are known for their decorative gold weights, pendants, and other jewellery products that served as regalia (Rattary, 1927; Busia, 1951; McLord, 1981; Ross, 1982, Antubam, 1963; Kyeremanten, 1965; Fosu, 1994) for utilitarian and communicative purposes.

The use of artistic fashion accessories such as dresses, fabrics, footwear, headwear, brooches, earrings, belts, bangles, anklets, amongst others, have always had a strong political, social and cultural role in safeguarding the histories, values, and identities of different cultures. It implies that these fashion objects give hints that help to unravel particular histories surrounding their origin, material, tools, semiotics, and creators in society. Of the accessories that served as regalia, one of the commonest, yet essential and inevitable fashion objects for Asante kings/chiefs, and by extension Akan and even non-Akan chiefdoms is ahenema (native sandals). The usage of ahenema goes beyond Ghana. Some kings/chiefs in neighbouring countries such as Togo and Cote D'ivoire also use it as essential regalia for traditional functions. There have been instances where ahenema has seemingly been used as panoplied regalia and an authoritative object of the power of a king/chief. Ghanaweb (2007, August 18) reports of the Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II’s destoolment of the Asomfohene, Nana Osei Kwabena, for flouting the chieftaincy orders of the Asante Kingdom. The destoolment process included the removal of his ahenema sandals to signify that the said chief has been destooled under Asante chieftaincy tradition. There were also reports that the Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, in December 2010 destooled the Queen of Atwima, Obaapanin Asamoah Duah II, and two sub-chiefs for taking a bribe (VibeGhana.com, 2010). As part of the destoolment rituals, the ahenema sandals of all the three culprits, which symbolised their office as traditional rulers, were removed from their feet. These instances of destoolment with the ahenema seemingly playing a symbolic role need further investigation. This is because the instances raise questions of the sociocultural relevance of ahenema regalia in Asante chieftaincy culture. Besides, the historical twist to the origin of this fashion object and regalia needs academic attention. This study, therefore, traces the historical origin of ahenema, and investigates its sociocultural relevance in Asante chieftaincy cultural milieu.

The theoretical perspectives that support this study is the object-based theory propounded by Lou Taylor. The study is situated in the object-based theory propounded by Lou Taylor (2002) and Riello’s (2011) methodological model of material culture of fashion. The object-based theory is concerned with materiality which has to do with description and documentation to bring out and classify garments or objects for historical purposes. It also focuses on the contextual attributes of the exhibits, oral history, company history, and design philosophy of fashion production (Taylor, 2002; Skou & Melchior, 2008). Riello’s (2011) methodological model of material culture of fashion which he borrowed from art history, anthropology, and archeology also makes fashion art objects central to historical studies and narratives be it socio-cultural, economic, and other practices of a particular period (Essel, 2017). Informed by object-based theory and material culture of fashion, the study considered the contextual attributes of ahenema, its oral history, design philosophy, description and documentation to bring out its history and sociocultural relevance amongst the Asantes and by extension, the Akan chieftaincy. This theoretical stance took ahenema fashion art object as central to historical studies and narratives in a sociocultural context.

Historical case studies constituted the research designs for the study. The historical case study helps in analyzing cases from the distant past to the present, using eclectic data sources, in generating both idiographic and nomothetic knowledge (Widdersheim, 2018). The use of the historical case study was informed by the fact that although case studies and histories can overlap, the case study’s unique strength lies in its ability to deal with a variety of evidence including documents, artifacts, interviews, and direct observations, as well as participant-observation beyond what might be available in a conventional historical study (Yin, 2018). A total of nine (9) respondents were purposively sampled for the study. They consisted of four (4) ahenema designers and producers with active experience ranging from 20 to 35 years on the job, two (2) chiefs and three (3) elders from chief palaces in Asanteland. Unstructured interview and focus group discussion constituted the method of data collection. Permission was sought from the respondents for face-to-face interview with the agreement to audio-tape for transcription purposes. Historical and narrative analysis tools were the data analysis tools used. With the historical research tool, the study used the heuristic of considering the source and the context of the data and corroborate it to ensure the trustworthiness and authenticity of the data gathered. Historical research concerns itself with identification, analysis, and interpretation of old texts (Špiláčková, 2012), eyewitness accounts, and other oral history and interviews. Using the narrative structure, data analysis was done to accentuate consistency, suppress contradiction, and produce rationally sound interpretation (Holloway & Jefferson, 2000) without truncating the content of the told stories about the lived experiences of the respondents. The historical narration was supported with photographs of ahenema taken with the permission of the creators. The transcribed and analysed data was shared with the respondents for verification purposes. The respondents also provided some pictures and permitted the researcher to use them for academic purposes. To ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents, pseudonyms were used in place of the original names.

The Akan word ahenema literally means ‘children of kings/chiefs.’ Legend has it that, when it was developed, only kings/chiefs and their families could wear it to show their status as royals. Later, it became permissible for the subjects and all to use. The king/chief belonged to the high class of society because they were the leaders of their flourishing kingdoms and ethnic states respectively. They had creative artists in their courts who produced functional and decorative artworks and fashion accessories used as body adornments. Per the high status of kings/chiefs in the society, the trickle-down theory, where new fashion art usage begins with the top echelon of society and gradually gets to the masses, exemplifies the spread and use of ahenema in Ghanaian society. Ahenema is also called Kyawkyaw. The word Kyawkyaw was derived from the sounds it makes when worn for the usual characteristic majestic walk. Respondent Opanin Kwame explained that:

Ahenema used to be worn by only the chiefs/kings and their families. If you are not a chief … you are not permitted to wear it. When the one who is not a chief is sighted wearing some at a durbar, the elders sent people to remove it from the person’s feet.

Legend has it that, the first ahenema was fashioned out of wood which served as the sole (called aseɛ) while the top (referred to as nsisoɔ or ahenemapɔnkɔ) was made of leather. It developed to a stage where the flat wooden soul was replaced with layers of animal skins, cut out to form the shape of the sandals. The animal skins (for example, okohoma) used as the sole produced the kyawkyaw sound when in use. The sound became the name of the sandals.

Respondent Opanin Antwi and Opanin Kwaku have been in the business of Ahenema production for more than thirty-five years. They make a living from the job, and have trained more than ten 10 and 16 apprentices respectively, some of which have set up their production shops. In a focus group discussion, they revealed that:

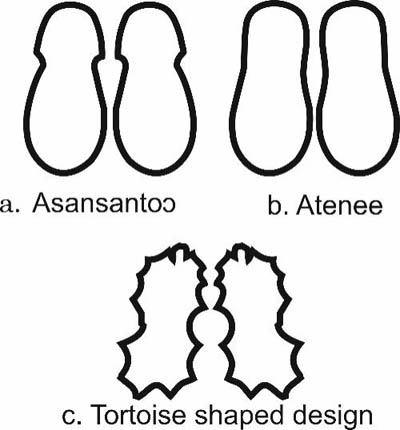

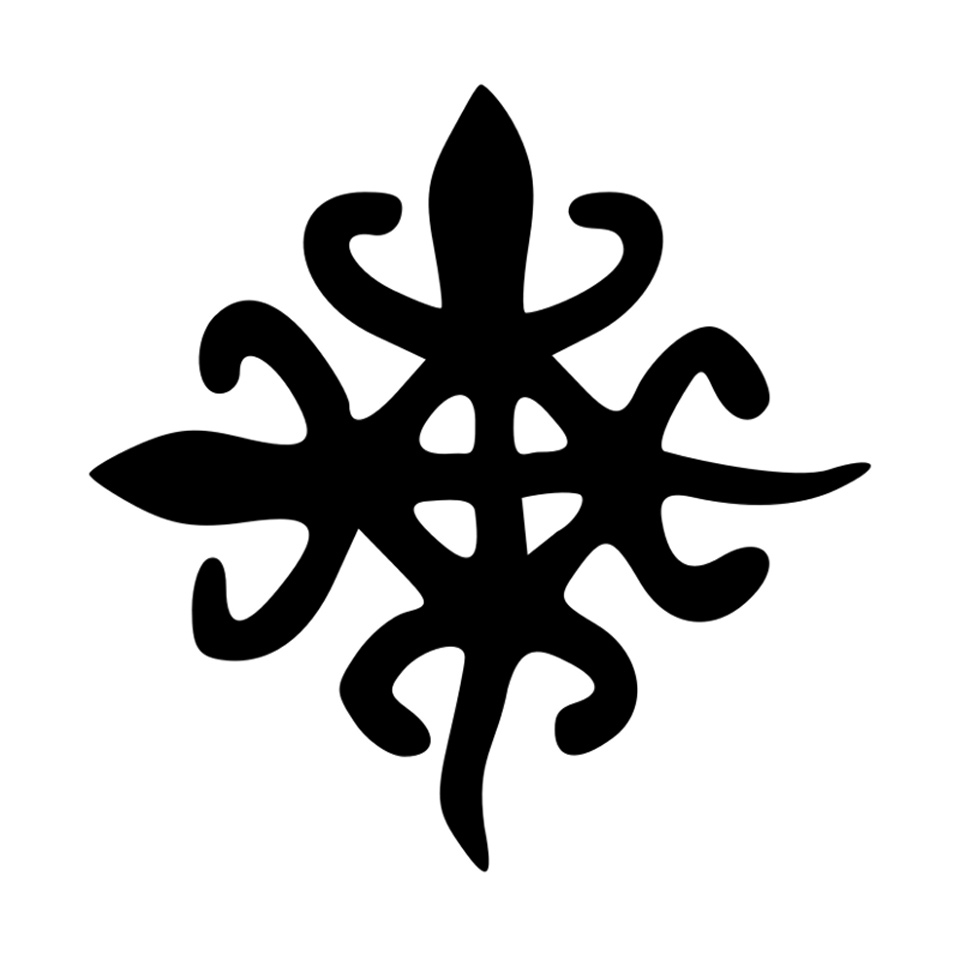

There are two basic soles (aseɛ) of ahenema, namely Asansatoɔ and Atenee (Figure 1). Beyond these, producers create new ones which are sometimes suggested by clients. It could be in the shape of animals like crocodiles, lizards, tortoises (Figure 1c) or fish. The soles have symbolic meanings that are usually associated with the animal or objects which influenced its creation. However, it is the top (nsisoɔ) that determines the name of the ahenema.

Some of sole pattern designs of ahenema. © Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel

There are different schools of thought on the etymology of ahenema footwear. One legend account traces it to the reign of the fourth Asante king, Otumfuo Osei Kwadwo Okoawia who ruled from 1764 to 1777(‘A Guide to Manhyia Palace Museum’, 2003). This account posits that Asantehema (Queen mothers) had specially made sandals, for they do not walk barefooted in the courtyard of the palace. One of the Asantehema once got injured in the foot while walking without sandals. The wound, according to legend, took long to heal and became a great oath of the Asantehema. Since this account is believed to have occurred during the reign of Otumfuo Osei Kwadwo Okoawia, then, the fourth Asantehema, Nana Konadu Yiadom I (whose tenure began in 1768 – 1809), was the possible beneficiary of the earliest ahenema footwear.

Bodwich’s (1818) narrative accounts of the culture of the Asante people offer some hints on the history of the ahenema footwear. In his description of the regalia of the kings, he pointed out that (p.35) ‘their sandals were of green, red, and delicate white leather …’ In thick description of what the king wore Bodwich said, their royal sandals ‘of a soft white leather, were embossed across the instep band with small gold and silver cases of saphies’ (p.38). Gold pendants and designs of varied symbolism that show the power and wealth of the Asante kings were used to embellish their unique ahenema footwears. Vansina (1982, p.222) offered hints of the period of production and usage of some ahenema. She revealed some of the artefacts including sandals and cast of gold rings had production dates estimated in the range of 1700 to 1900. This confirms the eighteenth century as a possible period ahenema sandals production in Ghana began.

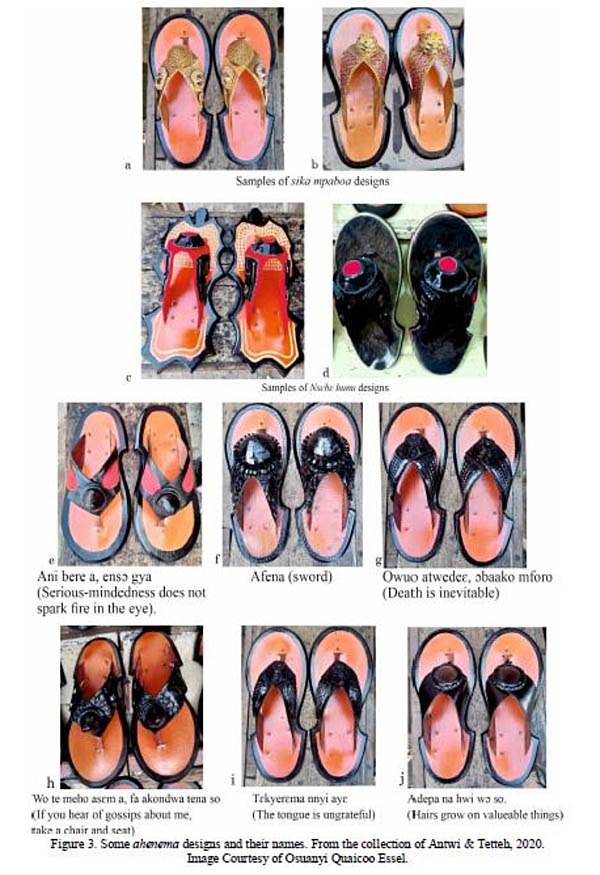

Categories of Ahenema. © Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel

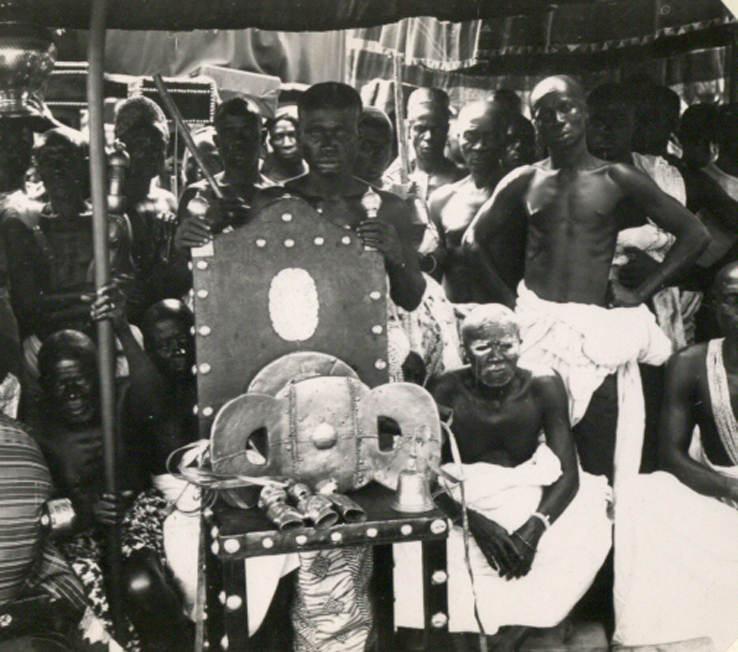

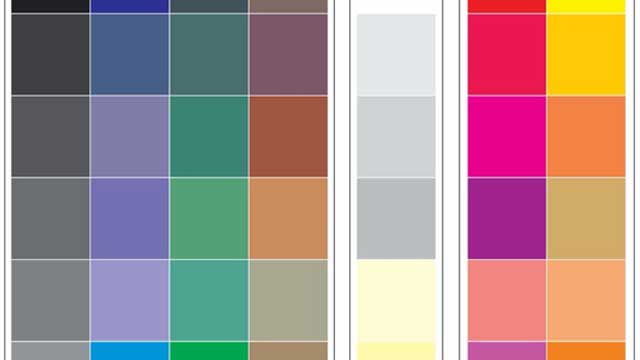

There are categories of ahenema (image above). The categories of ahenema are traditionally informed by the kind of occasion and the purpose for which they are made. There are those used for funerals, durbars and festive occasions (festivals and other merrymaking events), especially, in the customs and traditions of chieftaincy institutions. The red, black and brown coloured ones are usually used for funerals to depict bereavement, sadness and death. In the Akan notion of colours, red, black and brown are associated with decay, death, bereavement and pain (Antubam, 1963; Amenuke et al., 1991), hence, its association with funerals. Those meant for durbar (adwabɔ) are the gold stud sandals (Sika mpaboa), silver and related colours. One of the Akan chiefs commented that:

To complement the wearing of toga style by the chiefdom, they desired to develop footwear to match with it. As a result, they developed ahenema for different occasions. They created ahenema for funerals and durbars. But there are some people who are unaware of the types and, therefore, use them anyhow. This suggests that there are categories of ahenema worn for different occasions but certain factors have caused its improper usage in the traditional cultural milieu. These factors include ignorance of the colour symbolisms as well as the meanings ascribed to the entire design. In one breadth, the users who default the conventional usage in terms of colour schemes and meaning may be doing so for purely aesthetical reasons rather than meaning associated with them.

Amongst the Akans (which form over 70% of Ghana’s population), ahenema is the traditionally sanctioned footwear accessory suitable for traditional gatherings or occasions. Wearing the toga fashion (usually 6- 12 yards of fabric gracefully wrapped on the body) without ahenema is culturally inappropriate in the traditional chieftaincy milieu. Likewise, it is traditionally unethical and unacceptable in Asante customs and traditions for kings or chiefs to wear the toga fashion classic without wearing befitting ahenema. Even for those who are not part of the chiefdom, wearing ahenema that is unsuitable for a particular durbar, funeral and other traditional events of the chiefdom are likely to invite troubles for themselves.

Per the categorisation of ahenema sandals, sika mpaboa (literary translated as ‘golden footwear/sandals) for example, is the highest status-defining type of ahenema footwear amongst the chiefdom. For the chiefdom in the Asanteland, sika mpaboa (Figure 3) is a preserve of the Asante King. No other paramount chief could wear it without his approval. Based on the achievement of chiefs under the rulership of Asantehene, he may honour a chief with sika mpaboa. Such honours remain a great chieftaincy laurel, privilege and meritorious achievement in the Asanteland. Once a chief has bestowed this honour, it implies that that chief has the power to wear sika mpaboa at traditional chieftaincy functions, durbars, or occasions. The sika mpaboa of the Asante king remains distinctive. It may be decorative with cast-gold (Ross, 1982) symbolic animal and geometric figurines that ornament the (top) nsisoɔ of the sandals. Bodwich (1818, p.256) confirms this centuries-old and long-standing tradition of who has the prerogative to wear sika mpaboa (ahenema stud with gold or golden colours). He writes:

The caboceers of Soota [Nsuta], Marmpon [Mampong], Becqua [Bekwai], and Kokofoo [Kokofu], the four large towns built by the Ashantees at the same time with Coomassie [Kumasi], have several palatine privileges; … These four caboceers, only, are allowed, with the King, to stud their sandals with gold.’

A chief who wears Sika mpaboa that is not sanctioned by the Asantehene to durbars and other traditional occasions is slapped with contempt. The act becomes contemptuous because it breaches Asante chieftaincy etiquette, customs and traditions, which is punishable. In support, one of the chiefs commented that: ‘Look, I’m a chief in the Asanteland, but I do not have the right to wear sika mpaboa. Should I wear it, I would be cited for contempt, for it does not show respect to the Asante King.’ There are ranks of chiefs. A subchief could not wear ahenema of a higher status and prestige such as sika mpaboa to a durbar of paramount chiefs. He will be cited for contempt. One elder recounts that:

We attended a durbar in the Asanteland. I wore a particular ahenema as part of my toga fashion. As custom demanded, I was part of the entourage that went to greet the chiefs at the durbar. While greeting, I overheard one of the subjects whispering to one of the chiefs, if I’m traditionally permitted to wear that particular ahenema. The chief sighed in the affirmative in response to his subject due to my status in the traditional area (N. K. Duah, personal communication, October 19, 2020).Ahenema names and Semiotics

As in the case of wax print fabrics, ahenema are given unique symbolic and proverbial names. The names are usually given by the producers. In some cases, the client suggests the preferred name for the producers to fashion the sandals based on that. Respondent Opanin Kwame added that:

We came to meet some of the design names given by some of the earlier ahenema producers. We also create some designs and name them based on Akan symbolism associated with animals, plants, human body parts, adinkra symbols, among others. I have personally created some designs based on periwinkles which are small marine snails. Per its tiny nature, many people usually eat it when they don’t have money to buy fish or meat. People, therefore, consume it in difficult times. Based on this I used the shells of the periwinkles in my ahenema design and named it Me nso meho behia da bi which literally means ‘I will be useful to people one day’.

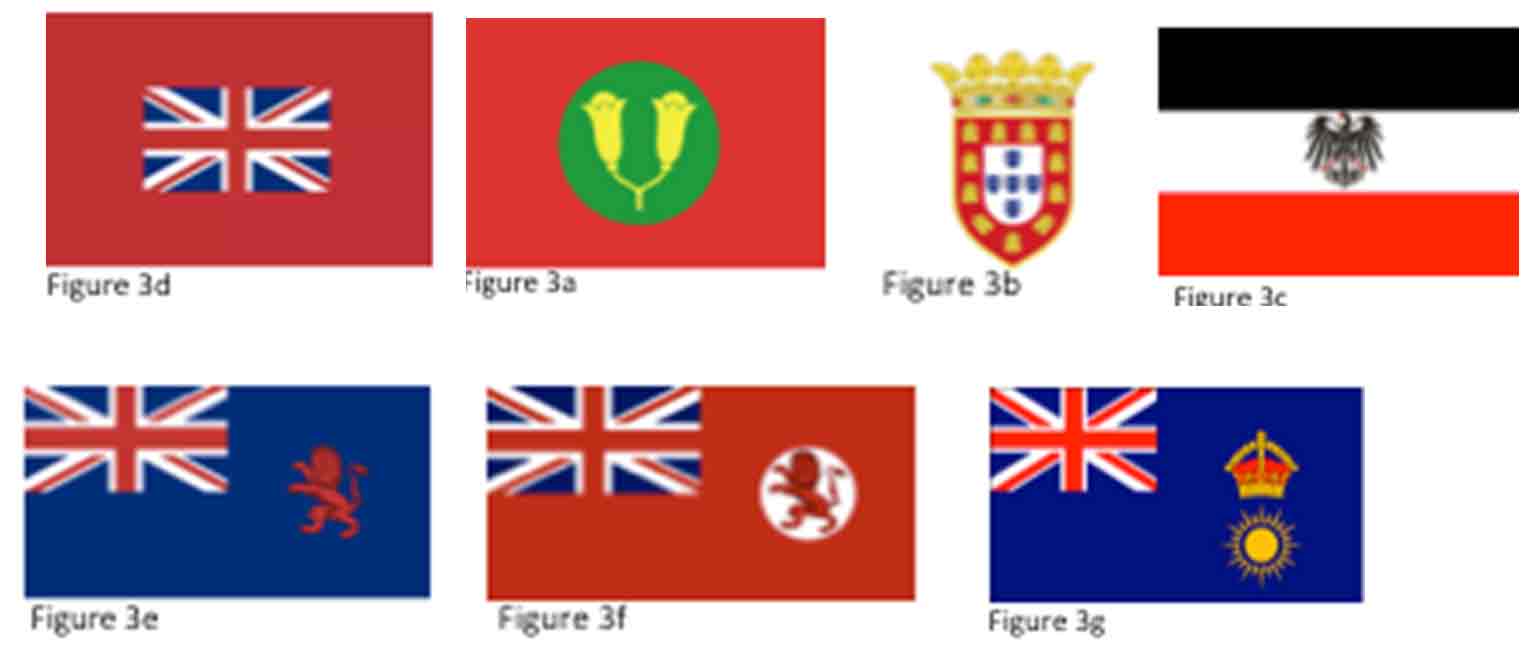

The names given by the producers or suggested by the clients may cast insinuations, promote peace, warns against the ills of society and show one’s status. Some of the names are presented in Table 1 and Figure 3 respectively. For example, Ani bre a, ensɔ gya design (Figure 3 e), shows red-dyed leather used as in-lay against the black colour scheme to suggest the symbolism of it name. The red parts of the design look seed-like, an abstract representation of reddening eye, which symbolically suggests seriousness. Philosophically, this treatment connotes that no matter the degree of seriousness in pursuing something, it will not cause the eyes to redden. In other words, seriousness, as an attribute does not mean one has to be boisterous or overly expressive. One could be serious and yet show a calm disposition.

In the production of ahenema, some producers specialise in making the sole (called aseɛ) while others specialise in making the top (referred to as nsisoɔ). Both the sole and the top have their unique names. However, when the top is fixed onto the sole, the name of the top becomes the name of the ahenema.

Meaning of some ahenema designsName of ahenema Meaning Ani bre a, ensɔ gya. Serious-mindedness does not spark fire in the eye. Ebididi bi ekyi. There are classes/grades in things Enku me fie, na enkosu me abontene. Do not kill me home and turn to sympathize with me in public. Da bɛn na me nsoroma bepue? When will my star arise? Abuburo nkosua, adea ebɛyɛ yie no, ɛnnsɛe da. Something that is destined to succeed will never fail. Asaase tokru, oibara bewura mu bi. All are susceptible to death. Wo te meho asɛm a, fa akondwa tena so. If you hear of gossips about me, take a chair and seat. Tɛkyerɛma nnyi ayɛ. The tongue is ungrateful. Nsɛbɛ hunu. Powerless talisman Kɔtɔ didi mee a, na ɛyɛaponkyerɛni ya. When the crab is well fed, the frog becomes jealous. Ebusua dɔ funu. The extended family cares overly for the dead body. Ebusua te sɛɛ kwayieɛ. A family is like a forest. Akokɔ nae tia ba, na ennkum ba. The legs of the hen step on its chicks, but it does not kill them.

Ahenema symbolisms in enstoolment and destoolment

Ahenema is considered as irresistible chieftaincy regalia in the scheme of Akan customs and tradition. Without it, the adornment of any Akan king or chief becomes incomplete. This implies that it holds a central position in the chieftaincy diplomacy and culture. As a result of its inevitable role in that regard, it has become symbolic regalia in both enstoolment and destoolment of kings and chiefs. When a chief goes contrary to the etiquettes, rules and regulations, taboos, customs and traditions in his/her role which tantamount to destoolment, the removal of his/her ahenema from his/her feet is a symbolic sign of destoolment. One of the chiefs explained that:

When a chief faulter, the queen mother and the council of elders that throne, removes the ahenema from the feet of the culprit chief to show that s/he has been destooled. The affected chief could seek redress from the paramount chief under which s/he serve.

Likewise, in the enstoolment process, wearing ahenema signifies his/her authority. In both the enstoolment and destoolment process, the sandals connote power, authority and might. Beyond enstoolment and destoolment, the Akan observe some etiquette in the usage of ahenema because of its symbolism to show respect to the elderly or powers that be. One has to negotiate a partial withdrawal of the feet from the ahenema as a sign of respect and demonstration of custom adherence during the greeting of the elderly or chief at durbar or public gathering.

Ahenema occupies a central place in the chieftaincy institution, customs and traditions of the chiefdom and the life of Asante people, and by extension the Akan of Ghana. It has remained essential regalia that is inseparable from the customs and traditions of the Akan. Though the regalia is associated with the Akan, it was developed by the Asante people. As a culturally essential fashion object, its historical origin and socio-cultural relevance in Asante chieftaincy cultural tradition which remains largely uncharted was the focus of this study.

By delving into oral history, supported with available historical documents, the study positioned the root of ahenema (also called Kyawkyaw) regalia designing and production as an eighteenth-century Asante phenomenon during the reign of the fourth Asante king, Otumfuo Osei Kwadwo Okoawia who ruled from 1764 to 1777; and the queenship of Nana Konadu Yiadom I. The Asantehema Nana Konadu Yiadom I, whose tenure began in 1768 – 1809, was the beneficiary of the earliest ahenema regalia. Subsequently, ahenema became regalia for the chiefdom, a tradition which has remained unchanged; and spread to both Akan and non-Akan states and kingdoms till now. Some chiefdom in parts of Togo and Cote d'Ivoire use the regalia. From the chiefdom, the regalia did trickle-down to the masses. To be ablest with the evolving designs of ahenema in the twenty-first century require extensive documentation of existing ones for posterity. Also, the creators of ahenema designs need to be saved from the clouds of anonymity to reveal their creative contributions in fashion accessories production.

Ahenema design and production are informed by the purpose and functions (occasion) for which they are made. There are designs meant for funerals, durbars and festive occasions (festivals and other merrymaking events), by traditional authorities in the observance of the customs and traditions, while there those made for purely utilitarian and aesthetical reasons. The Akan notion of colours applies in the designs for the chiefdom. Of all the ahenema, sika mpaboa (ahenema stud with gold), is regarded as the most prestigious, for it is the preserve of Asantehene. A chief under his reign could be honoured with sika mpaboa. With ahenema assuming a fashion object of huge socio-political and cultural connections and signification, it would be of interest to delve into the power politics of ahenema and how it is used to negotiate self-actualisation among the chiefdom.

The regalia, Ahenema, has unwavering socio-cultural power in the (un)making of kings/chiefs in Akan culture in the realms of enstoolment and destoolment rituals of Asante chiefs as well as Akan chiefs as a whole. Ahenema are given unique symbolic and proverbial names by its original producers and, in some cases clients. The names have philosophical meanings that need decoding to fully understand the language of ahenema. In the traditional sense, failure to understand the language of ahenema, may land one into contempt.

References- A Guide to Manhyia Palace Museum. (2003). Ashanti Region Kumasi. Otumfuo Opoku Ware Jubilee Foundation.

- Bodwich, T. E. (1819). Mission from Cape Coast castle to Ashantee, with a statistical account of that kingdom, and geographical notices of other parts of the interior of Africa. W. Bulmer and Co.

- Busia, K. A. (1951). The position of the chief in the modern political system of Ashanti. Frank Cass.

- Ghanaweb (2007, August 18). Otumfuo sacks chief. http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/economy/artikel.php?ID=129165

- Essel, O. Q. (2017). Searchlight on Ghanaian iconic creative hands in the world of dress fashion design culture (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Education, Winneba.

- Fosu, K. (1994). Traditional art of Ghana. Dela Publications and Designs.

- Holloway, W. & Jefferson, T. (2000). Doing qualitative research differently. Sage Publication Ltd.

- Kyerematen, A.A.Y. (1965). Panoply of Ghana. Longmans, Green and co Ltd.

- McLeod, M. D. (1981). The Asante (87 – 111). The Trustees of British Museum.

- McCaskie, T. C. 2000. Asante Identities. History and Modernity in an African Village 1850-1950. Edinburgh University Press.

- Rattray, R. S. (1927). Religion and Art in Ashanti. Oxford University Press.

- Ross, D. H. (1982). The heraldic lion in Akan art: A study of motif assimilation in Southern Ghana. Metropolitan Museum Journal, 16, 165 – 180.

- Špiláčková, M. (2012). Historical research in social work – theory and practice. ERIS Web Journal, 3(2), pp. 22 – 33.

- Vansina, J. (1984). Art history in Africa. Longman Group Limited.

- VibeGhana.com. (2010). Otumfuo destools chiefs for taking bribe. http://vibeghana.com/2010/12/15/otumfuo-destools-chiefs-for-taking-bribe/

- Widdersheim, W. M. (2018). Historical case study: A research strategy for diachronic analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 40(2), 144 – 152.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods. Sage.

-

Natalie Göltenboth

Natalie GöltenbothWhen I first entered Anna’s house1, I was surprised to hear that it was a temple of the Afro-Cuban Santería religion, a place determined by the presence of the orichas – the sacred beings of Santería. The objects of the interior did not reveal but seemed to hide their sacred meaning for the uninitiated viewer.

On our way through the house, Anna introduced me to a doll dressed up in white: Obatalá, the paternal oricha of wisdom and justice, with a cream cake on his right and a wide-eyed Bambi on his left. On the sideboard in the corner we greeted Yemayá, the maternal oricha of the sea, represented by a plastic bowl filled with water in which various floating animals swung and a Barbie, whose light blue lace dress complemented the turquoise colored water of the bowl. Finally, in a small wardrobe, the soup tureen of the goddess Ochún was decorated with two elegant Barbies in golden outfits, staring out of the darkness with their always flawless smiles. Two foreigners, charged with western ideals of beauty, who, in this context, had been commissioned with representing Ochún, the oricha of femininity, love and freshwater.

The representation or illustration of sacred powers through everyday objects, such as toys, dolls and knickknacks, have held a strong fascination for me since I literally stumbled upon them in Santero households, and, thus, the question of how this transference of powers and meanings to ultimately mundane objects could occur has long accompanied me on my fieldwork.

How can we interpret the fact that Ochún, the Afro-Cuban goddess of love and freshwater is visualized by a glittering Barbie doll sent to Cuba by Cuban family members living in the USA.

We should take a look back to the beginnings of the history of this religion for a better understanding of these dolls on the altars of Afro-Cuban Santería. Between the 16th and the 19th century, people were moved from one world to another on the sea routes of the transatlantic slave trade, which connected West Africa with the Caribbean (and this, in turn, with Europe), where they would henceforth work as slaves on the plantations of white landowners.

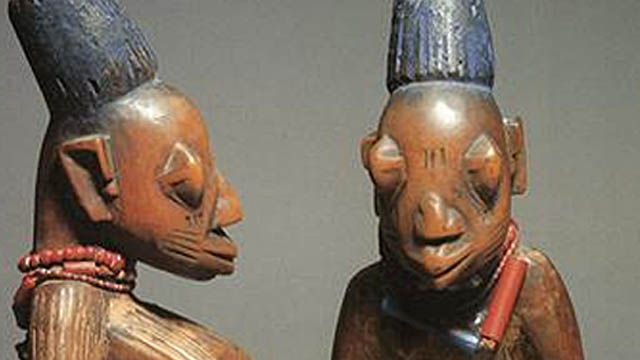

We should consider that people from Nigeria, Togo and Benin who had been deported to Cuba arrived in the New World without any luggage. The carved wooden sculptures of their gods, power objects, masks or costumes were left behind together with the African coastline. The transfer of religious concepts from Africa to Cuba, the Caribbean or Brazil, therefore, took place primarily in the minds of these people and remained dependent on this imaginative reservoir for long periods of time.

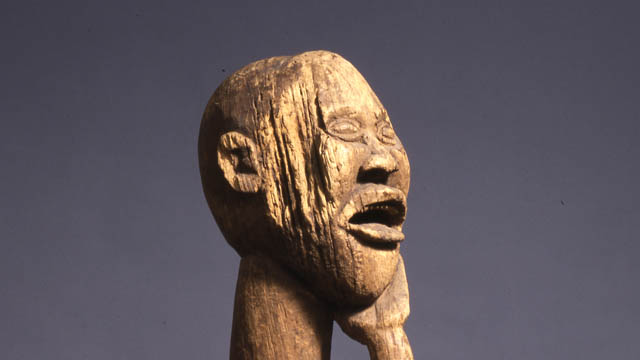

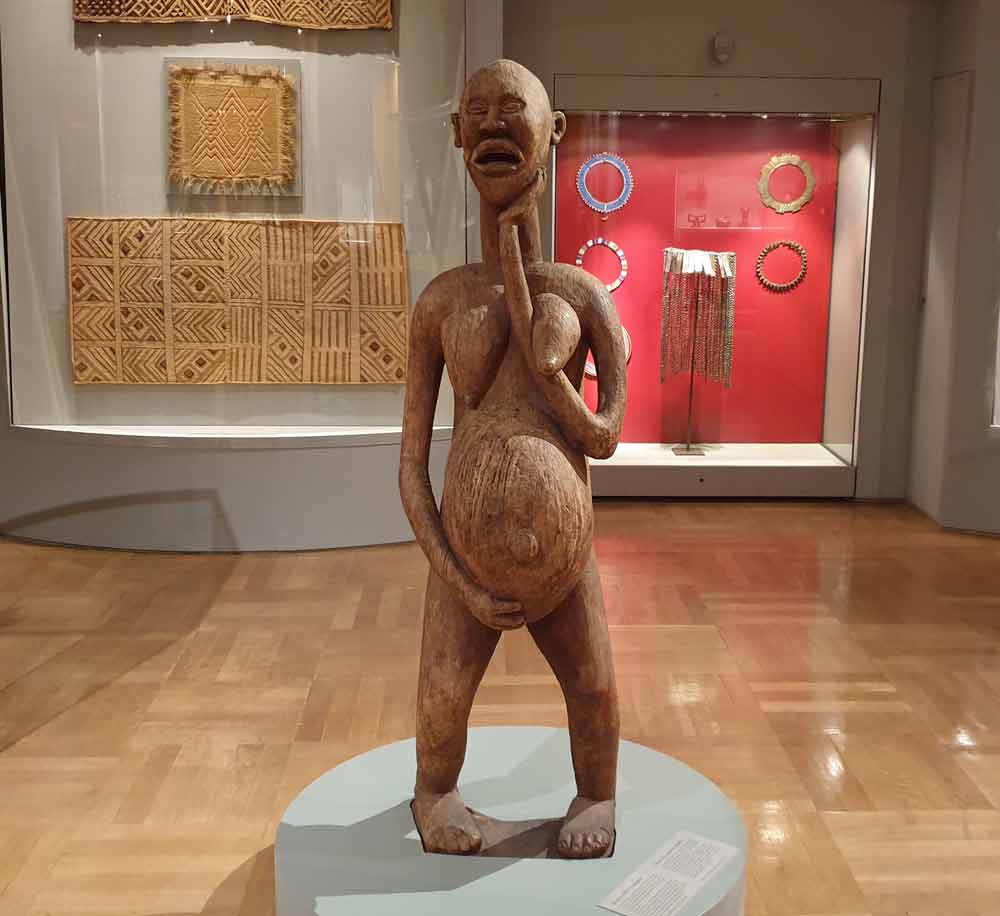

Despite the fact that the Cuban social anthropologist Don Fernando Ortiz2 still managed to collect some old carved wood oricha representations which had been produced during the colonial period in the 1930s to 1950s, the tradition of carving sculptures had not been resumed in the new situation in Cuba. The wooden oricha representations of Nigeria and Benin were replaced by smooth porcelain Madonna statues and the serious looking saints of Spanish folk Catholicism. Slaves from West Africa who were forced to worship the statue of Santa Barbara reacted with a phenomenon known as the syncretism of the Caribbean: statues of the Madonna and saints were interpreted as “reservoirs” of African deities and treated as such.

In the course of these syntheses, Santa Barbara is venerated as a representation of the virile oricha Changó, ruler of fire, thunderstorms and lightning. The Virgin of Regla, with her blue and white Madonna robe, is associated with Yemayá, the maternal oricha of the sea, and the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, in her church near Santiago de Cuba, is worshipped as Ochún, the oricha of love, creativity and sexuality. This possibility of reinterpretation, of “declaring something to be something else,” is tantamount to breaking the link between form and content and is the precondition for the unusual appearance of Barbies on the Santería altars.

As the colonial supplies in holy figurines diminished, colorful multiples of saints from Cuban mass production are found nowadays instead of the statues. Together with plastic dolls, Barbies or everyday objects, these new assemblages bear witness to the change of time and values, of new desires and new myths that move the people of Cuba today and are visualized on the altars.

Despite the fact that the connection of object and meaning has been blown up in modern Santería arrangements, it remains unclear to what extent new narratives are woven into the conception of the orichas when they are represented by new material objects: how much Madonna can one find in Yemayá, the oricha of the sea, and what is the relationship between a Barbie and an oricha? Referring to Marshall McLuhan’s3 famous statement that the medium is a significant part of the message, we can try a more specific interpretation of Barbies on Santería altars.

Original Barbie dolls are commodities acquired in stores in the USA and sent as gifts by relatives. As commodities and gifts, they mirror family ties that have continued over decades connecting Cuba and the USA, countries that have been politically separated since the Cuban revolution in 1959. In addition, Barbie dolls are not only saturated with the sacred aura of the orichas, they are also simultaneously encrusted with a fine texture of Cuban dreams of consumption and the feverish delirium of departure. Like Catholic saints, Barbies are figurines which are highly charged with their own narrative: the story of Ken and Barbie in the US American glamour world is a story of success, power and consumption. In this sense, Barbies on Afro-Cuban altars represent the fusion of idealized body and lifestyle imaginaries with sacred Afro-Cuban entities and deified ancestors. And, in the end, the forces of the orichas are conjured for reaching exactly these reasons: to provide their adepts with power that enables them to achieve their goals and realize their dreams – be they capitalistic or of another sort.

The reclassification of the Barbie doll from toy to altar object does not happen suddenly. The dolls have to undergo a transition process to become part of an altar installation. The dolls that appear on altars have been subjected to a ritual cleansing ceremony using decoctions of herbs associated with a particular oricha, which allows them to bear the vital power “Aché” of the sacred being. A bundle of herbs and other substances have been placed inside their bodies. Throughout these preparations, nothing has changed the appearance of the doll, which preserves its fashionable style and smile. What has changed is the idea about the object and hence its place – the Barbie is now part of a sacred altar installation.

Barbie dolls watch the strollers from the illuminated doorways that line the dark streets of Havana. Powerful representations of forces, imaginations, places and practices, connecting Africa and Cuba as well as Cuba and the USA, blending boundaries between dolls and gods, toys and power objects, commodities and sacred beings. They connect long-separated families and fragmented religious concepts. They guard the entrances of homes and watch over the desires of their inhabitants, who rely on the power of their Barbie goddesses.

Footnotes

1) Natalie Göltenboth. “Yemayá und der Spielzeugdampfer – Zur Sakralität der Ready-mades auf afrokubanischen Altären.” In Ideen über Afroamerikaner – Afroamerikaner und ihre Ideen. Beiträge der Regionalgruppe Afroamerika auf der Tagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Völkerkunde in Göttingen 2001, edited by Lioba Rossbach de Olmos & Bettina Schmidt. Marburg: Curupira, 2003, pp. 107-127.

2) Fernando Ortiz. Hampa Afrocubana: Los Negros Brujos. Miami. Universal, 1973.

3) Marshall McLuhan. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Men. 1st Ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill, 1964

References

- Brown, David H. “Thrones of the Orichas. Afro-Cuban Altars in New Jersey, New York and Havana”, African Arts, Oct. (1993) 44-87.

- Danto, Arthur C. Transfiguration of the Commonplace. A Philosophy of Art. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Göltenboth, Natalie.2020. „Invoking the gods – or the apotheosis oft he Barbie doll“ IN: Philipp Schorch, Martin Saxer et al. Exploring Materiality and Connectivity in Anthropology and Beyond. London: UCL

- Göltenboth, Natalie. “Yemayá und der Spielzeugdampfer – Zur Sakralität der Ready-mades auf afrokubanischen Altären.” IN: Ideen über Afroamerikaner – Afroamerikaner und ihre Ideen. Beiträge der Regionalgruppe Afroamerika auf der Tagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Völkerkunde in Göttingen 2001, edited by Lioba Rossbach de Olmos and Bettina Schmidt. Marburg: Curupira, 2003, pp. 107-127.

- Holbraad, Martin, and Morten Axel Pedersen. “Things as Concepts.” In The Ontological Turn. An Anthropological Exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017, pp. 199-238.

- Willie Ramos, Miguel. “Afro-Cuban Orisha Worship.” In Santería Aesthetics in Contemporary Latin Art, edited by Arthuro Lindsay. Washington: Smithsonian Press, 1996, pp. 51-76.

-

Esther Kibuka-Sebitosi

Esther Kibuka-SebitosiSouth Africa gained its independence in 1994 with Nelson Mandela becoming the first black President on the fall of apartheid. The problem was: Even after the demolition of the apartheid system, social cohesion was a challenge as people still lived and gathered in separate groups, according to their race. Freedom had come but the people still segregated themselves. One of the ways to promote social cohesion is through sport. The hosting of the 2010 World Football cup therefore was a welcome opportunity.

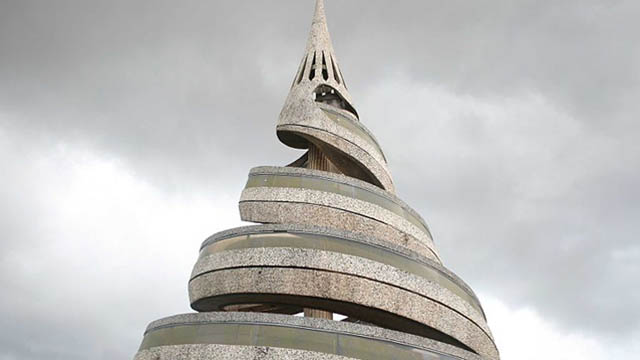

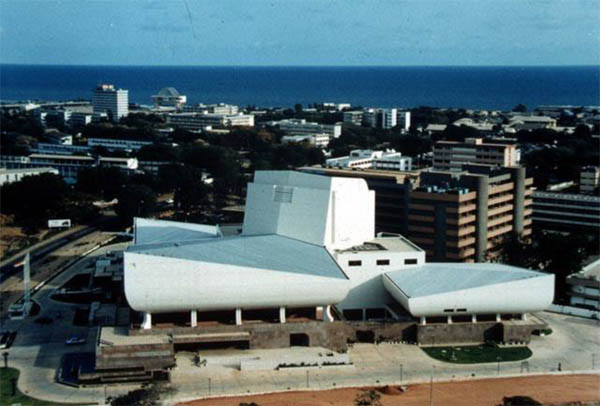

The photograph shows the First National Bank Stadium or simply FNB Stadium. It is also known as the Calabash, because of its resembling an African vase. It is located near Nasrec and bordering Soweto and Johannesburg.

The Department of Arts and Culture defines Social cohesion as “the degree of social integration and inclusion in communities and society at large, and the extent to which mutual solidarity finds expression among individuals and communities”. This means that South African communities or society is cohesive when “ the extent that the inequalities, exclusions and disparities based on ethnicity, gender, class, nationality, age, disability or any other distinctions which engender divisions, distrust and conflict are reduced and/or eliminated in a planned and sustained manner. Thus, with community members and citizens as active participants, working together for the attainment of shared goals, designed and agreed upon to improve the living conditions for all”.

Based on the above understanding, building a nation is a complex process that entails “a society with diverse origins, histories, languages, cultures and religions come together within the boundaries of a sovereign state with a unified constitutional and legal dispensation, a national public education system, an integrated national economy, shared symbols and values, as equals, to work towards eradicating the divisions and injustices of the past; to foster unity; and promote a countrywide conscious sense of being proudly South African, committed to the country and open to the continent and the world“.

The hosting of the World Football Cup therefore was an optune moment in the history of the nation. According to Barolsky, (2011) sport was used as a catalyst to build a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic, prosperous and free South Africa. The FIFA World cup in 2010 referred to it as „African and South African. The Bafana Bafana team received great support from home. The social cohesion was divided into three dimensions: Civic, Social and Economic."

The impact of the FIFA World cup was significant in building social cohesion. There was little doubt that the World cup was an “extraordinarily unifying moment for the country as whole, which broke down social, racial and even gendered barriers as women were increasingly drawn into the fervor around the a game usually predominantly watched by men.” (Barolsky, 2011)

References

- Barolsky, V (2011).Impact of 2010 soccer World Cup on social cohesion and nation-building, Technical Report · January 2011.

- DOI: 10.13140/2.1.2007.5841

- Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271700976

- Department of Arts and Culture statement on Social Cohesion

published April 2020

-

Karimatu Dauda

Karimatu DaudaMany of the group of pupils that were trained on Bura culture and Bansuwe dance in Ruby Springfield College are from this ethnic group, Bura. However, a good number of these pupils did not have prior experience of the Bansuwe dance. Consequently, the facilitator who taught them the dance relied on videos of Bansuwe dance and songs, played through a computer and a portable speaker, to teach them the dance steps from the scratch. This was accompanied by direct demonstrations and direction by the facilitator. Although the facilitator is not a specialised dance teacher, she is from the Bura ethnic group and a skilled Bansuwe dancer who had been performing for many years.

The lady in yellow was a parent of one of the dancers who came to cheer the dancers. The person in green is the principal of the school who also came to cheer the dancers. Cheering of dancers and throwing some money at them is a common practice in Nigeria. It is meant to both encourage and show appreciation to the dancers. (Photo: Karimatu Dauda)

Bansuwe dance is popular among the Bura and is usually the preferred cultural dance at weddings, funerals and other important ceremonies. Yet, the experience in this school shows that there are a good number of Bura people whose children do not know the Bansuwe dance. Part of the reasons for this is that some of the children have never been taken to their villages where cultural practices are better sustained. The Boko Haram conflict in the region also discourages social gatherings which are often potential soft targets of insurgents.

The cultural day events usually involve the presence and participation of pupils’ parents and other guests which makes it a good channel for the sustainability of culture. More girls ended up performing in the dance because many of the boys were unable to pass the final screening for the cultural day. The dancers were dressed in traditional Bura attire called Japta. The audience cheered the dancers and at intervals some would join the dance briefly. This dance was accompanied by traditional Bura music made by drums, xylophone, flutes and vocals.

The boy with the basket was picking the money thrown to the dancers by the audience in appreciation of their performance. (Photo: Karimatu Dauda)

The pupils, especially those from Bura, could easily learn more about the Bansuwe dance from their parents and relatives at home. Since dance often carries specific meanings within the social settings it is situated (Pusnik, 2010), there will not be a shortage of what to converse about concerning the Bansuwe dance. Traditional dance in Nigeria is used as a channel for communicating social values, sensitization and even carrying out social sanctions. In addition to these, Bansuwe dance is also used to convey merriment during ceremonies and sadness during funerals and each is reflected by the tone, tempo and messages of the music chosen.

Bansuwe Dance (Photo: Karimatu Dauda)

In the case of the cultural day of Ruby Springfield College, the dance was clearly conveying merriment and the central message of the song was that people should come together as friends and brothers. This message was according to the central purpose of the cultural day which was to encourage mutual cultural understanding among the pupils of the school.

The excitement accompanying the performance of Bansuwe dance by the pupils of Ruby Springfield College is a testimony to the fact that it left a lasting impression on them. This is because, for some pupils, it represented the first time they witnessed and participated in the Bansuwe dance. This enthusiasm by pupils, and even by some parents, is behind the determination by the school to sustain the practice of the cultural day annually. This in turn will ensure that Bansuwe dance is sustained, as younger generations get to learn and participate in it every year at school.

While the annual cultural day cannot be compared to dance subjects formally being taught in the classroom, it is no doubt a contribution to arts education albeit as an extra-curricular activity. It serves as the next best thing in the absence of a dedicated dance subject in the curriculum of schools. In addition, it will be an important space for the sustainability of Bansuwe dance possibly for many generations to come. It is important to sustain this dance because it is one of the few remaining cultural activities which brings together people of all ages, gender, and social status to interact equally on an informal basis. Such a gathering would provide a good space for the conversations on cultural sustainability.

Bansuwe Dance (Photo: Karimatu Dauda)

Arts education is part of the curriculum of primary, secondary and tertiary academic institutions in Nigeria. This does not mean, however, that the teaching of arts is done in every school in the country. The situation is further compounded by the fact that schools offering arts education are often selective about the arts subject they teach. In most schools, fine arts or creative arts make up the totality of their arts education subjects. While their creative arts subject includes lessons in music, dance and theatre, there are also dedicated music and theatre subjects in schools.

In contrast, dance is hardly, if ever, exclusively taught as a subject in formal education settings. Like in many other countries, dance is not taught with the same frequency and depth as painting, theatre or music (Mosko, 2018). Even if there were a dedicated subject for dance education in the country, the hundreds of ethnic groups in Nigeria would make the choice of what dance to teach in formal education settings quite challenging. This is because a typical classroom is made up of learners from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. Generally, arts education in the country is facing a number of challenges, as identified by Enamhe (2013), including the discouragement of children from taking arts subjects by parents, the fear of the perceived difficulty of the creative aspects is arts subjects, and the high cost of materials needed for arts education both for learners and academic institutions.

References

- Enamhe, B. B. (2013). The role of arts education in nigeria. African Journal of Teacher Education, 3(1), 1-7.

- Mosko, S. (2018). Stepping sustainably: The potential partnership between dance and sustainable development. Consilience: The Journal of Sustainable Development, 20(1), 62-87.

- Mtaku, C. Y. (2020). Continuity and change: The significance of the tsinza (xylophone) among the bura of northeast Nigeria. Center for World Music – Studies in Music, Universitätsverlag Hildesheim.

- Pusnik, M. (2010). Introduction: Dance as social life and cultural practice. Anthropological Notebook, 16(3), 5-10.

-

Esther Kibuka-Sebitosi

Esther Kibuka-SebitosiRainbow Nation

The rainbow in the Bible given in Genesis 9:16 is a reminder that we have a covenant with God not to destroy the earth again by floods. “I set My rainbow in the cloud, and it shall be for the sign of the Covenant between Me and the earth,” says the Lord. God had made a covenant with Noah and his seed for generations. Genesis 9:9. And I, “behold, I establish my covenant with you, and with your seed after you”. Since we are all Abraham’s seed, we are covered in this covenant, although Jesus makes a better covenant in the New Testament. Returning to the rainbow nation, this covenant is saying “ no more destructions”. It is as if God is saying we should no longer fight each other but live together in peace. He made us all people with different colours (rainbow).

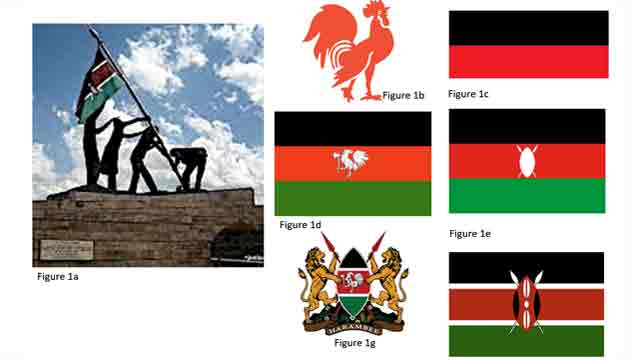

The metaphor describes a people with multi-cultures living together. The image of the flag is a symbol of togetherness or unity. The different colours. Adopted in 1994, the red, white and blue were adopted form the colours of the Boer Republic while the yellow, black and green were taken from the ANC (African National Congress) flag. The black colour is a symbol of the people; the green represents fertility of the land while the gold represents the wealth from minerals beneath the soil. The ANC adopted these colours way back in 1925.Associated with the flag is the national anthem. This is unique in that it has many languages:

- Nkosi sikelel’ Afrika

- Maluphakanyisw’ uphondo lwayo,

- Yizwa imithandazo,

- yethu,

- Nkosi sikelela,

- thina,

- lusapho lwayo.

- Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso,

- O fedise dintwa la matshwenyeh

- O se boloke (Ntate)

- O se boloke

- setjhaba sa

- heso,

- Setjhaba sa

- South Afrika

- – South Afrika.

- Uit die blou van onse hemel,

- Uit die diepte van ons see,

- Oor ons ewige gebergtes,

- Waar die kranse antwoord gee,

- Sounds to call to come together,

- And united we shall stand,

- Let us live and strive for freedom,

- In South Africa our land…

Songwriter: Cornelius Jacob Langenhoven

Summary

The Rainbow metaphor is characteristic of a nation that aspires for peaceful living; building a peaceful nation. The symbol taken from the Bible donating the Noahic covenant reminds us that God will no longer send the floods to destroy us.

The flag is a symbol of unity between the Boers and the African National Congress colours, which represents the whole of South Africa. It is a sign of hope and nation building.

Associated with the Flag and the Rainbow nation is the National anthem. It is written in many languages signifying the rainbow nation of multi-cultures.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainbow_nation

- https://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/flags/countrys/africa/soafrica.htm

published January 2020

-

Elfriede Dreyer

Elfriede DreyerThe Richtersveld National Park in South Africa has some of the most beautiful and hardy vegetation in the world. The 'botterboom' ('butter tree') (Tylecodon paniculatus) is but one example hereof. According to Wikipedia (RICHTERSVELD 2008), "The plant appears to have wide tolerance of growing habitats, growing in weathered rock in the north to coastal sands in the south. The plants can reach heights of 2 m making them the largest of the tylecodons. Tylecodon paniculatus is summer deciduous. The plants conserve energy by photosynthesizing through their 'greenish stems' during the hot dry summer months. The yellowish green, papery bark is a very attractive feature of this plant and has given rise to the common name. During the winter, plants are covered with long, obovate, succulent leaves clustered around the apex of the growing tip. [...] In nature the plants tend to grow in groups, making a spectacular show when they flower. [...] The shrub is reported to have a surprisingly weak and shallow root system for its size." This plant is representative of many other African succulents and bulbous plants that have shallow root systems and can therefore easily adjust to desert and other harsh environmental conditions. They change their leaves into thorns and the surface to protect the plant against the loss of water.

The metaphor of the succulent is of particular interest to an engagement with nomadic identity in the context of a continent such as Africa that has been subjected to "wicked, messy problems". Being similarly exposed to a severe environment, African people have accustomed themselves to survive in difficult circumstances and to a large extent have become nomadic as a result. In many cases they have adopted itinerant lifestyles and form groups for protection, safety and cultural coherence. Living on a vast continent, they are accustomed to long journeys; however, poverty, violence, civil wars, colonial and other imperial infiltrations and oppression have resulted in a focused nomadic condition where people are constantly moving and travelling in the search for a better life and even survival. Aligning contemporary culture with nomadism, Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (1996) appropriates the stereotype of the pilgrim who is on a teleological journey - ordered, determined and predictable - but cannot come to rest and leave a footprint in the sand. They operate through a 'shallow root system'.

Bulbous succulent plants are essentially botanical rhizomes, a concept that inspired the notion of the rhizome as a philosophical concept, initially developed by Gilles Deleuze (philosopher) and Felix Guattari (psychotherapist) in their Capitalism and schizophrenia (1972 -- 1980) project. Deleuze and Guattari (1987:7) state that the "rhizome itself assumes many diverse forms, from ramified surface extension in all directions to concretion in bulbs and tubers". In "A thousand plateaus" (1987 [1980]) they introduce the concept of the rhizome as follows (assigned to cultural patterning):

1. Principle of connection: any point of a rhizome can be connected to any other

2. Principle of heterogeneity: any point of a rhizome can be connected to any other

3. Principle of multiplicity

4. Principle of a signifying rupture: a rhizome may be broken, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines

5. Principle of cartography and

6: Principle of decalcomania: a rhizome is not amenable to any structural or generative model; it is a map and not a tracing.

Deleuze and Guattari's model allows for a cultural view that entertains non-stable relationships, subjectivity, relationalism, multiplicity and volatile positions. Similarly, Italian contemporary philosopher and feminist theoretician Rosi Braidotti (2011:3) views the nomadic predicament and its multiple contradictions have come to age in the third millennium after years of debate on the "'nonunitary' - split, in process, knotted, rhizomatic, transitional, nomadic - so that fragmentation, complexity and multiplicity have become everyday terms in critical theory." Since the 1990s Braidotti has been engaged with the question as to what the political and ethical conditions of nomadic subjectivity are, grounded in a "politically invested cartography of the present condition of mobility in a globalized world" (Braidotti 2011:4).

South Africa has experienced turbulent histories over the last two centuries and nomadic movement was brought on by volatile colonial, postcolonial and global upheavals, leading to political and social displacement and consequently hybrid identities. Having been a British as well as a Dutch colony, South Africa has since 1652 shown cultural patterns of movement in and out of the country, and from place to place. During apartheid non-whites or 'people of colour' were viewed as not belonging and were removed from the city; forcibly established in townships outside the city; only allowed as workers into the city; and had to carry passbooks (identity documents) on them all the time. For many decades now, in postapartheid South Africa, migrants from all over the continent have been flocking to the country in search of a better life and even survival, and they mostly live in temporary shelters. Many other sociological and cultural problems have emanated as a result of the migrant issue, based on subjective racism, xenophobia, crime and fear for the other.

Identity (and subjectivity) in the African modernist context is neither stable nor fixed, and the corporeality of the artist-as body and the artwork-as-process in this specific part of the world henceforth has produced liminalities in many ways. Often rooted in a rural or small-town environment, African artists generally tend to move to multicultural, cosmopolitan cities where gallery and industry networks are in closer proximity. Those in the rural remote parts of Africa make it their business to connect through digital and social media in order to stay connected, current and noticed.

The art of South African artist Diane Victor provides an eminent example of nomadic identity depiction. The artist utilises various ephemeral media in her work, such as ash, crushed charcoal and staining. In Perpetrator 1, 2008, a so-called smoke portrait, she has used the deposits of carbon from candle smoke on white paper to draw with. The work is exceedingly fragile and can be easily damaged, disintegrating with physical contact as the carbon soot is dislodged from the paper, and in this way speaks about the fragility, precariousness and insubstantiality of a nomadic human condition. Although the smoke portraits started with a series on AIDS victims in 2003, Victor continued to depict various other individuals, commenting on ephemeral politics and ideas, and life generally as a temporal entity. In this work she depicts a perpetrator with reference to the previous South African apartheid dispensation and the atrocities of its perpetrators, but also to counter racism and the violence committed in the name of political redress. The Perpetrator's race is indeterminate, but his gender is certain, as well as the cruelty of his dispensation. Severed from the body, the Perpetrator's head becomes a rhizome that is not 'rooted' in a body, but uprooted, derooted, and floating with tubular arteries as corms hanging from it like a beheaded monster.

As an ephemeral, nomadic image, Perpetrator 1 speaks about a decolonial condition that presents the ambivalent Baumanian idea of the pilgrim-tourist who keeps going in circles, driven by an ideological sense of survival. Nomadic identity is essentially rhizomatic, and in Africa, as in many other parts of the world, the drive to belong and the utopian quest for a better life have resulted in identity being redefined, renegotiated, rerooted and sprouting in many directions.

References

- Bauman, Z. ‘From pilgrim to tourist – or a short history of identity’. In Hall, S and Du Gay, P (eds). 1996. Questions of cultural identity. London/New Delhi/Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Braidotti, R. 2011. Nomadic subjects: embodiment and sexual difference in contemporary feminist theory. Second edition. Gender and culture: A series of Columbia University Press. New York: University of Columbia Press.

- Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. 1976. Rhizome: Introduction. Paris: Éditions de Minuit. [based on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s Capitalism and schizophrenia project (1972 - 1980)].

- Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. 1987 [1980, French original]. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Athlone Press.

- RICHTERSVELD NATIONAL PARK - VEGETATION: BOTTERBOOM (Tylecodon paniculatus). 2008.Available: https://www.richtersveldnationalpark.com/vegetation_botterboom.html (Accessed 3 January 2019).

published April 2020

-

Ebenezer Kow Abraham

Ebenezer Kow AbrahamTheophilus Kwesi Mensah and the Placemaking Paradigm

Within the rebranding and the making of new identity for Winneba as enshrined in the Effutu Dream Project, the name Theophilus Kwesi Mensah cannot be overlooked in this intercourse. This is not only because he engineered the widely talked about installations: the Unity Monument, The Aboakyer Monument, The Fishermen of Akosua Village and the Monument of Ofarnyi Kwegya but the awe-striking aesthetical connotations he incorporated in the aforementioned works. Each of these statues were rendered to mimic the idea of Winneba as a community built on a collective space. Being native of Winneba, heightened his understanding of how the amalgamation of economic, political, and cultural activities in the past, would accord him the impetus to express himself publicly. In so doing, he empowered his sculptures to ventriloquy the unique narratives that define Winneba and redefine this relatively old settlement yet burgeoning municipality as a dwelling place or a place worth visiting.

Figure 1: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Ofarnyi Kwegya, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Yeepimso Community Centre, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

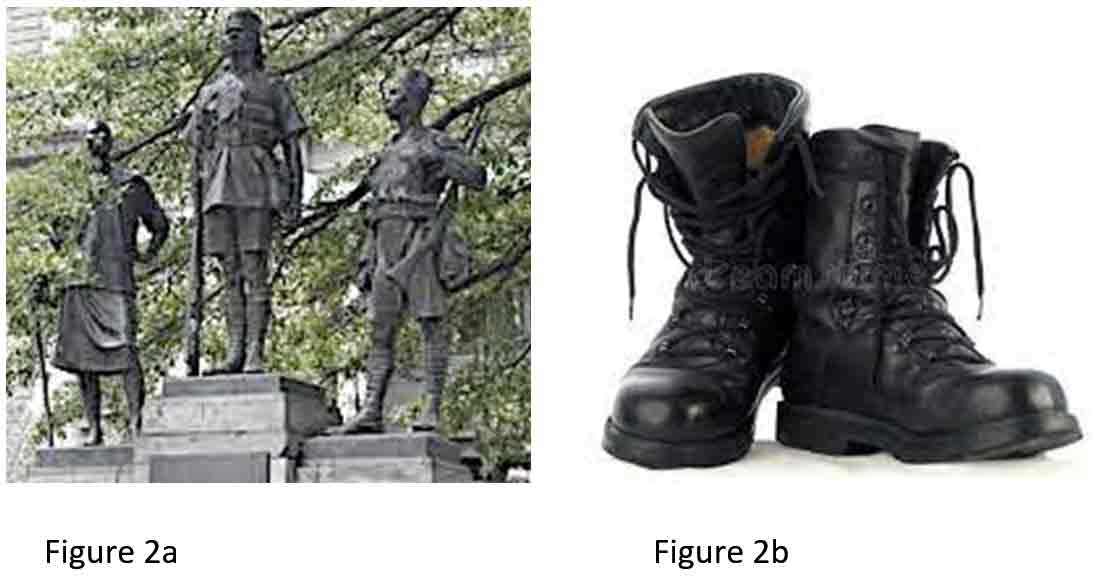

Through the lens of placemaking, Ofarnyi Kwegya (Figure 1) and the Fishermen of Akosua Village (Figure 2) are two typical statues that has beautified the vernacular space of two historical settlements in the older southern half of Winneba.

Figure 2: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Fishermen of Akosua Village, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Akosua Village Community Centre, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

The two statues stand in the middle of Yeepimso and Akosua Village communities respectively as embodiments of vital ingredients helping in creating a sense of community, civic identity, and culture in both spaces. They have both transformed their unique sites as lively and attractive communities with the monumental figures not just becoming legible maps to the sites but turning the spaces into places that support human interactions. The site of the statue has become the most important and attractive places in the two communities. They have become the center of attraction where the community gather for entertainment and trade, especially at night when economic activities in the two communities are at their peak.

Figure 3: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Unity Monument, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. The Unity Square, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

Another compelling monumental statue that has transformed the landscape of its site is the Unity Monument (Figure 3). Before the advent of the monument, the site of the statue (the Y-intersection – Winneba Traffic Light) was a deserted barricaded mere chaparral which displayed all forms of notices including obituaries and political posters (Mensah & Abraham, 2022). Yet, Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s statue has transformed the space into an ideologically charged space for a deliberative unity and peace agenda in Winneba. The environment is so aesthetically pleasing that people like to visit the site for selfies and sightseeing thereby generating income for the Municipal Assembly.

Figure 4: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, The Aboakyer Monument, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Osimpam Museum, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s ontological orientation of Winneba is multifaceted. Hence, he found significance in the century’s old festival of the people of Winneba, Aboakyer to sculpt a monumental statue to this honour (Figure 4). The Aboakyer Monument mounted on the roof-top of the Osim Pam Museum is at the heart of Winneba as an embodiment of Winneba’s heritage. Owing to the enormous narratives surrounding the Aboakyer Festival, it is seen as one of the most popular and most significant festivals in Ghana (Akyeampong, 2019). The people of Winneba are invariably identified by the Aboakyir Festival. Theophilus Kwesi Mensah captured the very essence of the festival by vividly depicting the most significant characters: the Supi, the Asafo warriors, and their cheer leaders in procession with the catch.

During the 2022 Aboakyer Festival, it was observed that both celebrants and tourist were awe-struck by the aesthetic connotations of the monument. People gathered around the site for various reasons. Whilst some were seen taking tourist photos, others were seen venerating the ancestors who in the past led the festival.

In view of the Effutu Dream Project, Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s artistic ingenuity to a large extent has contributed to rebranding the Winneba Township by beautifying the place and making it attractive for tourist. However, beyond the beautification agenda, part of the underlining philosophy of the statues was to consciously bring to the fore, some compelling memories of Winneba in relation to the current narratives within the land.

Theophilus Kwesi Mensah and the Collective Memories of Winneba

Theophilus Kwesi Mensah capitalized on his creativity to translate some notable historical events pertaining to his beloved native, Winneba into tangible remnants of the recent past to shape and, indeed, consolidate the Effutu Dream Project. Whilst usurping a storyteller, he equipped his statues to mimic the historiography of Winneba as collective memorials for the publics of Winneba. This is underpinned by his inclination to the truism that cities are built based on their histories and for that matter, Winneba cannot be gentrified without laying claims to the past publicly. Therefore, he ensured that whilst the Effutu Municipal Assembly initiated the Effutu Dream Project, the glorification of the public triumphs of Winneba was not taken for granted. This desire culminated into transforming some important public vernacular spaces into storehouse of memories embedded and inscribed on the landscape of Winneba.

Figure 5: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Ofarnyi Kwegya, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Yeepimso Community Centre, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

Figure 6: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Fishermen of Akosua Village, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. Akosua Village, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

Knowing Winneba traditionally as a fishing community, Theophilus Kwesi Mensah produced two major monuments, Ofarnyi Kwegya (Figure 5) and the Fishermen of Akosua Village (Figure 6) as a concretized instantiation to the noble trade that has in the past defined what place Winneba is. Ofranyi Kwegya, is the statue of the unheralded giant master fisherman, an exponent of mid water trawling in Winneba who captured huge number of fish whereas the Fishermen of Akosua Village depict the famous trio: Zagada Afadzinu, Kwami Akpade and Sogbka Dagodzo who introduced artisanal fishing or subsistence fishing to Winneba.

Although the fishermen portrayed in these monumental statues have died long ago, they constitute such significant heroes in the historiography of Winneba. In view of their important roles in the socio-economic phenomenology of Winneba, Theophilus Kwesi Mensah aimed at stopping their decay and position them into the realm of the timeless with the erection of their statues as memorials that transmit their archetypal narratives.

Figure 7: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah, Unity Monument, 2021. Fibre Reinforced Polymer. The Unity Square, Winneba. Courtesy of Edem Dedi Photography.

In view of Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s understanding of the political and dynastic heritage of Winneba, he engineered the construction of the Unity Monument in commemoration of the end of the protracted chieftaincy feud that had ensued in Winneba in the past. Ephraim-Donkor (2019) recount that since the latter part of the nineteenth century, the people of Winneba have clashed in violent struggle for power until 22nd July, 2015 when the Supreme Court of Ghana, finally intervened. The feud was rooted in an uncanny clash of cultures within the same family three, resulting in a political quagmire as to which succession mode to follow, the male or female model. The people of Winneba traditionally follow the patrilineal line of succession, however the Acquahs who are for the female model, tasted power as caretakers but refused to cede power back to the original benefactors, the Otuano Royal Family (Gyatehs or Gharteys) who are for the male model.

The female model became popular in Winneba because of their hospitality which allowed their Akan neighbours to live with them and rendered Winneba as a cosmopolitan community. Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’ depicted the two families, Gharteys and the Acquahs and a third figure representing the non-natives as a united force in the gentrification of Winneba as they erect a flag as signifier to this commitment. The Unity Monument does not only exhibit an aesthetically astute display of Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s artistic ingenuity but also, it encapsulates the political and dynastic history of Winneba whilst being a crucible of memory to the unity and peace in Winneba presently.

As part of Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s memorialization agenda with regards to his statues in Effutu Dream, he produced the iconic Aboakyer Monument as a memorial to the Aboakyer Festival of the Effutus of Winneba. The Aboakyer, known throughout Ghana as the "Winneba Deer Hunting Festival," is held annually in early May. It commemorates the founding of Winneba some three centuries ago, when the Effutu, led by one Osim Pam and accompanied by the god Penkye Otu, settled on the coast at the end of their migratory journey from northern Ghana to the present location.

Pedagogical Connotations of Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s Statues in Effutu Dream

As artist academic, having been under the tutelage of the Emancipatory Art Teaching Project (EATP) by Professor kąrî’kạchä seid’ou, he is an alley of the blaxTARLINES community in Kumasi. Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s practice ties in with contemporaneity in the arts. In his teaching, he identifies with the philosophy that trainee art educators ought to think and act creatively. He does this by championing their epiphany in the studio as nexus of exploring emerging issues in art education. Through the studio, his statues in Effutu Dream creatively imparts on his students as agents of transformation in addressing the urgent call for equity, diversity, and inclusion in our educational structure and practices.

Whilst his students have the liberty to choose their own masters, he has been readily available, and the doors of his studio was opened to all students who loved art whilst working on his statues in Effutu Dream. After all, he too has absorbed lessons from legendary Ghanaian Artist Academics such as Benjamin Menya, Kwamevi Zewuze Adzraku and Buckner Komla Dogbe. So, students with varied backgrounds are mainstays in his studio beyond the statues in Effutu Dream. He reckons the studio space as a crucible of intellect and a window to add to knowledge as his students pick his brain as apprentices there.

Figure 8: Theophilus Kwesi Mensah working with his students (Courtesy the artist)

Despite his inclination to EATP, he does not sway from being a traditionalist in the sense that he continues to enjoy working from the human figure. His preference to the human figure in his statues in Effutu Dream was informed by the truism that life changes and the language of sculpture evolves. So, it does not really matter if he is being repetitious with a subject that has preoccupied sculptors throughout history. Yet, as didactic symbols, he sought to make explicit what many sculptors make implicit in contemporary memorials in a classical sense with his figurative renditions.

Whilst the public may tend to be passive receptors of his statues in Effutu Dream, his students cannot afford to be indifferent. There are obvious educational imperatives they naturally cannot ignore. As far as they look and see the statues, there are predisposed to learn from them by asking questions. Reis (2010) citing Silva (1984) concerning public art claimed that even if we do not pay any attention to it, daily contact influences our attitude towards the conservation of artworks and our intellectual and sensory appropriation of them. What more do students need to get motivated in their studies aside having the opportunity to see the works of their lecturer installed all over the community? As artist academic, Theophilus Kwesi Mensah thrives to integrate his vast knowledge in the art into the practice of cultivating artistic design talent. His contribution to knowledge is application oriented. His statues in Effutu Dream make meaningful contributions to practical solutions that are at the core of art education. His students garner the nuances of what he says in the classroom when they see his statues in town.

Conclusion

Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s ingenuity as a sculptor, draftsman and an academician are undeniable, so too is his energy and prolific creative output in the wider Effutu Dream Project. Within a trilogy of paradigms, he displays a profound representation of Winneba as a beautiful place to live and work. He does so by immortalizing four important collective memories of the town whilst using Fibre Reinforced Polymer, a material that stands the test of time and exudes a sense of eternalness. In the process, his students tapped into his creative sense both at his studio and on site.

Whilst Theophilus Kwesi Mensah’s artistic praxis is eclectic, what I have sketched is a heuristic effort to describe his monumental contribution in the Effutu Dream Project in his beloved Winneba where he lives and practice as artist academic. The few details I have carved may at times be minor, but they add up to have a larger impact to his contributions in the effort to redesign and develop Winneba.

References

- Akyeampong, O. A. (2019). Aboakyer: traditional festival in decline. Ghana Social Science Journal, 16(1), 97.

- Farman J (2015). Stories, spaces, and bodies: The production of embodied space through mobile media storytelling. Communication Research and Practice 1(2): 101–116.

- Mensah, T. K. & Abraham, E. K. (2022, June). The unity monument: A hope of the end to the political quagmire in simpa. Paper Presented at The Creative Arts Conference, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

- Reis, R. (2010). Public art as an educational resource. International Journal of Education through Art, 6(1), 85-96.

-

Bernadette Van Haute

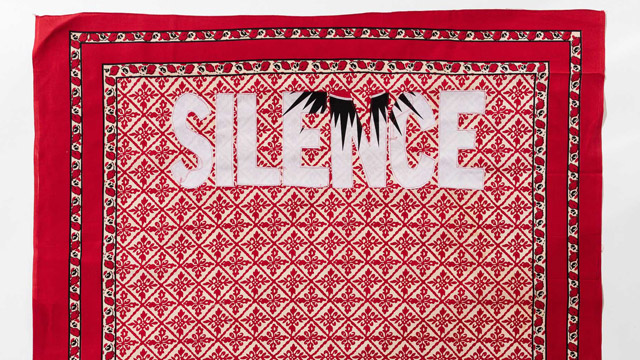

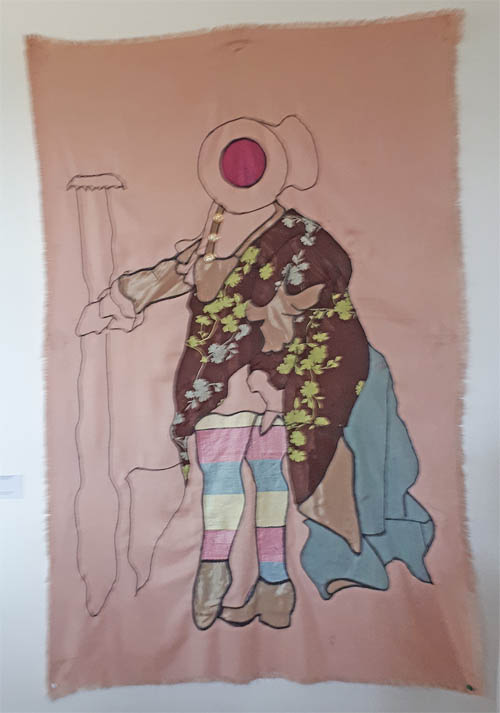

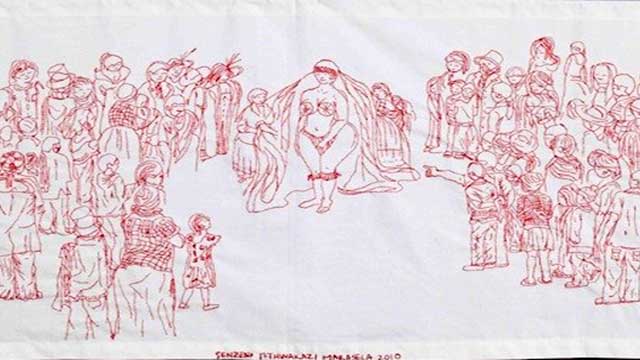

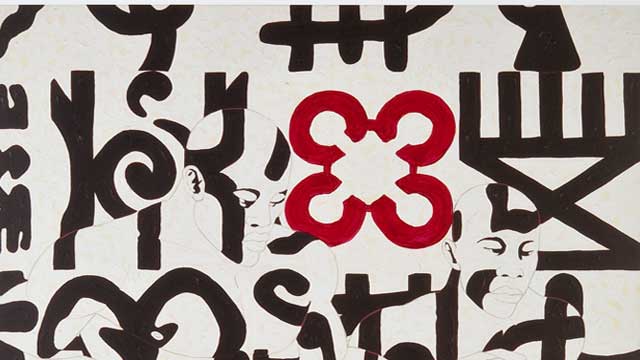

Bernadette Van HauteLawrence Lemaoana’s work, entitled SILENCE … FALLS (2017) consists of Kanga fabric with cotton embroidery, measuring 155 x 115 cm. Lemaoana is a South African black male, born in Johannesburg in 1982, who lives and works in Johannesburg. The work serves as an example of the ways in which young black artists in South Africa aim to express a specific South African identity which appeals to the global art world.

The use of Kanga fabric as medium is in itself very significant. Lemaoana states that: "Kanga fabrics [...] are used extensively in my work. Manufactured in the East, and brought to South Africa to be sold in markets and bazaars, the journey of the fabrics speaks of the idiosyncrasies and trade imbalances of globalisation. The textiles themselves though have a wholly different life in South Africa – they are regarded as significant markers of spiritual healing, imbued with great religious and spiritual power, used by diviners and fortune-tellers." (Afronova)

The Kanga cloth is “used specifically in Emandzawe rituals, both as clothing for the sangoma [diviner] performing the ritual and as cloth on the shrine inside the shrine room in which the ritual takes place” (von Veh, 2017, pp. 13-14). The use of this fabric thus establishes Lemaoana’s identification with both global culture and black African culture which does not belong to a mythical past but is still very much alive today. His own familiarity with the sangoma becomes clear when he maintains that the ambiguity of the traditional healer’s utterings parallels that of headlines in the news media. He also exploits the deeper meaning embedded in the three colours white, red and black to heighten the impact of his highly topical messages.

Lemaoana’s work is inspired by current socio-political events and the way in which they are reported in the local media. The composition Silence Falls evokes the #RhodesMustFall movement which began in 2015. This demonstrates the artist’s concern with the plight of the South African youth and his identity as an artist born in the 1980s – the so-called ‘born-frees’ who did not actually experience the ‘struggle’. The works of this generation of artists are described as “symptomatic of the new identity issues of the post-apartheid era. This young generation is appropriating a history that it believes has been confiscated and twisted in order to develop an alternative that takes into account its own subjective experience. Conscious of their responsibilities, these artists are helping to formulate and affirm a specific South African identity” (Pagé and Scherf, 2017, p. 8).

Lemaoana expresses his concern with socio-political issues through a critical engagement with mass media in South Africa. He is particularly concerned by the ability of the local media to shape social consciousness. By isolating news headlines and appropriating political slogans in his very own cynical way he “turns didactic and propagandistic tools on their head” (Afronova). As Lepage (2017, p. 117) states, Lemaoana uses the power of “words as favoured instruments in the political struggle”.

The importance of Lemaoana’s work is vested in his participation in the Fondation Louis Vuitton exhibition in Paris in 2017. The exhibition was divided in three parts; the first one was entitled Being there: South Africa, a contemporary scene and aimed to show South African vitality through the works of 16 artists. In the accompanying catalogue the curators Suzanne Pagé and Angeline Scherf (2017, p. 8) explained that their choice of artists was “based primarily on the action of the artists themselves, on their engagement with the current economic and social institutions, their awareness and conviction that they can act and play a role: BEING THERE”.

Interestingly the curators also comment on the fact that this younger generation of artists, in the context of ongoing economic and social divisions more than two decades after the end of Apartheid, sees it as its mission to transform “disenchantment into the energy for renewal” (Pagé and Scherf, 2017, p. 8). Achille Mbembe (2017, p. 16) elaborates on the current tensions in South African politics and culture which have led to a stalemate. In a society where consumption has become the quintessential state of being, the visual arts are in crisis, characterised by radical fragmentation and dispersion of reality (Mbembe 2017, pp. 23-24). “What is needed in contemporary South African arts”, writes Mbembe (2017, p. 24), “are concepts with which to seek out the real … . This will not happen without a new collective imagination that will help to facilitate the passage from the past and present to the future”.

This is what Lemaoana has achieved in his art. His participation in the show confirms his status as a contemporary South African artist who has managed to decolonise his art by “seeking out the real” and grounding it in a local or national context. Furthermore, in Lemaoana’s works there is no room for, what Mbembe (2017, p. 25) calls, “tropes of pain and suffering” or the injuries inflicted “by the forces of racism and patriarchy” – tropes that are the characteristic traps of postcolonial discourse. His art is decolonised in the sense that all the resources of cultural and artistic modernity – both in terms of medium and narrative – have been mobilised in order to render itself more relevant to a modern Africa and a global humanity (Ekpo, 2017, p. 20).

References

- Afronova. http://www.afronova.com/artists/lawrence-lemaoana-2/ (accessed on September 19, 2017).

- Ekpo, D. (2017). Manifesto for a Post-African art. Unpublished keynote address presented at the SAVAH Conference, Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa, September 21 – 23, 2017.

- Lepage, A. (2017). Lawrence Lemaoana. In S. Pagé & A. Scherf (Eds.), Being there: South Africa, a contemporary scene (pp. 116-21). Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Editions Dilecta.

- Mbembe, A. (2017). Difference and repetition. Reflections on South Africa today. In S. Pagé & A. Scherf (Eds.), Being there: South Africa, a contemporary scene (pp. 15-25). Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Editions Dilecta.

- Pagé, S. & Scherf, A. (Eds.). (2017). Being there: South Africa, a contemporary scene. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Fondation Louis Vuitton and Editions Dilecta.

- von Veh, K. (2017). Textual Textiles: Gender and Political Parodies in the Work of Lawrence Lemaoana, TEXTILE,1-19. doi: 10.1080/14759756.2017.1337381 (Accessed September 5, 2017).

published March 2020